Why It Matters

Faster float‑to‑string conversion reduces latency and CPU usage in high‑throughput data services, while shorter representations improve storage efficiency and network bandwidth.

Key Takeaways

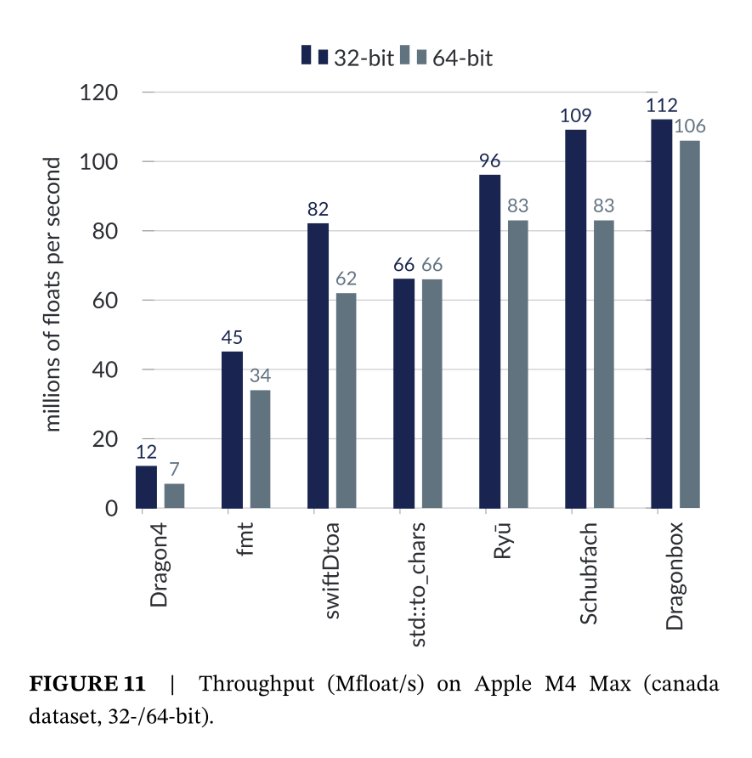

- •Dragonbox and Schubfach lead performance.

- •Ryū close behind, all ~10x faster than Dragon4.

- •String generation now 20‑35% of conversion time.

- •std::to_chars uses up to twice needed instructions.

- •No current method always yields shortest decimal representation.

Pulse Analysis

The conversion of binary floating‑point values to human‑readable decimal strings underpins virtually every data‑exchange format, from JSON APIs to CSV logs. Historically, the Dragon4 algorithm introduced in 1990 set the baseline for correctness, but its performance quickly became a bottleneck as data volumes grew. Modern alternatives—Dragonbox, Schubfach, and Ryū—rely on clever integer arithmetic and pre‑computed tables to eliminate costly division steps, delivering a tenfold speedup that translates into measurable latency reductions for large‑scale services.

Benchmarking these techniques reveals a shifting cost profile: while the core arithmetic now executes in a few hundred CPU instructions, the final string‑assembly phase accounts for 20‑35% of total runtime. This overhead, once negligible, is now a target for optimization, especially as compilers and hardware evolve. The study also highlights that the standard C++17 function std::to_chars, though convenient, consumes nearly twice the instruction budget of the most efficient hand‑tuned implementations, and the popular fmt library lags slightly behind. Such gaps suggest room for library authors to adopt the newer algorithms and streamline instruction paths.

For developers, the practical takeaway is clear: adopting Dragonbox or Schubfach via open‑source libraries can cut serialization costs dramatically, benefiting high‑frequency trading platforms, telemetry pipelines, and cloud‑native microservices. The research also exposes a subtle correctness nuance—no current routine guarantees the absolute shortest decimal representation, which can affect storage and bandwidth when dealing with massive numeric datasets. All code, benchmarks, and test data are publicly available, inviting the community to refine implementations further and push the limits of floating‑point serialization efficiency.

Converting floats to strings quickly

When serializing data to JSON, CSV or when logging, we convert numbers to strings. Floating-point numbers are stored in binary, but we need them as decimal strings. The first formally published algorithm is Steele and White’s Dragon schemes (specifically Dragin2) in 1990. Since then, faster methods have emerged: Grisu3, Ryū, Schubfach, Grisu-Exact, and Dragonbox. In C++17, we have a standard function called std::to_chars for this purpose. A common objective is to generate the shortest strings while still being able to uniquely identify the original number.

We recently published Converting Binary Floating-Point Numbers to Shortest Decimal Strings. We examine the full conversion, from the floating-point number to the string. In practice, the conversion implies two steps: we take the number and compute the significant and the power of 10 (step 1) and then we generate the string (step 2). E.g., for the number pi, you might need to compute 31415927 and -7 (step 1) before generating the string 3.1415927. The string generation requires placing the dot at the right location and switching to the exponential notation when needed. The generation of the string is relatively cheap and was probably a negligible cost for older schemes, but as the software got faster, it is now a more important component (using 20% to 35% of the time).

The results vary quite a bit depending on the numbers being converted. But we find that the two implementations tend to do best: Dragonbox by Jeon and Schubfach by Giulietti. The Ryū implementation by Adams is close behind or just as fast. All of these techniques are about 10 times faster than the original Dragon 4 from 1990. A tenfold performance gain in performance over three decades is equivalent to a gain of about 8% per year, entirely due to better implementations and algorithms.

Efficient algorithms use between 200 and 350 instructions for each string generated. We find that the standard function std::to_chars under Linux uses slightly more instructions than needed (up to nearly 2 times too many). So there is room to improve common implementations. Using the popular C++ library fmt is slightly less efficient.

A fun fact is that we found that that none of the available functions generate the shortest possible string. The std::to_chars C++ function renders the number 0.00011 as 0.00011 (7 characters), while the shorter scientific form 1.1e-4 would do. But, by convention, when switching to the scientific notation, it is required to pad the exponent to two digits (so 1.1e-04). Beyond this technicality, we found that no implementation always generate the shortest string.

All our code, datasets, and raw results are open-source. The benchmarking suite is at https://github.com/fastfloat/float_serialization_benchmark, test data at https://github.com/fastfloat/float-data.

Reference: [Converting Binary Floating-Point Numbers to Shortest

Decimal Strings: An Experimental Review](https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/spe.70056), Software: Practice and Experience (to appear)

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...