UK Faces Rising Undersea Threat, MPs Warned in Stark Evidence Session

•February 10, 2026

0

Why It Matters

Under‑sea disruption could cripple essential services and national security, making it a frontline defence priority for the UK and its allies.

Key Takeaways

- •Russia's deep‑sea ops outpace Western uncrewed tech.

- •Atlantic Bastion concept remains largely theoretical, power limited.

- •UK's sonar and acoustic libraries provide strategic advantage.

- •Undersea infrastructure vulnerability threatens national security and economy.

- •US Orca XLUUV program over budget, signals technology risk.

Pulse Analysis

The strategic importance of the seabed has surged as adversaries weaponise under‑water domains. Russia’s specialised deep‑sea unit, GUGI, and China’s expanding undersea capabilities target critical cables, pipelines and data routes that underpin the UK’s economy. While physical cuts to cables are common, the real danger lies in coordinated disruption that can undermine financial markets, energy supplies and governmental communications, turning a technical nuisance into a geopolitical lever.

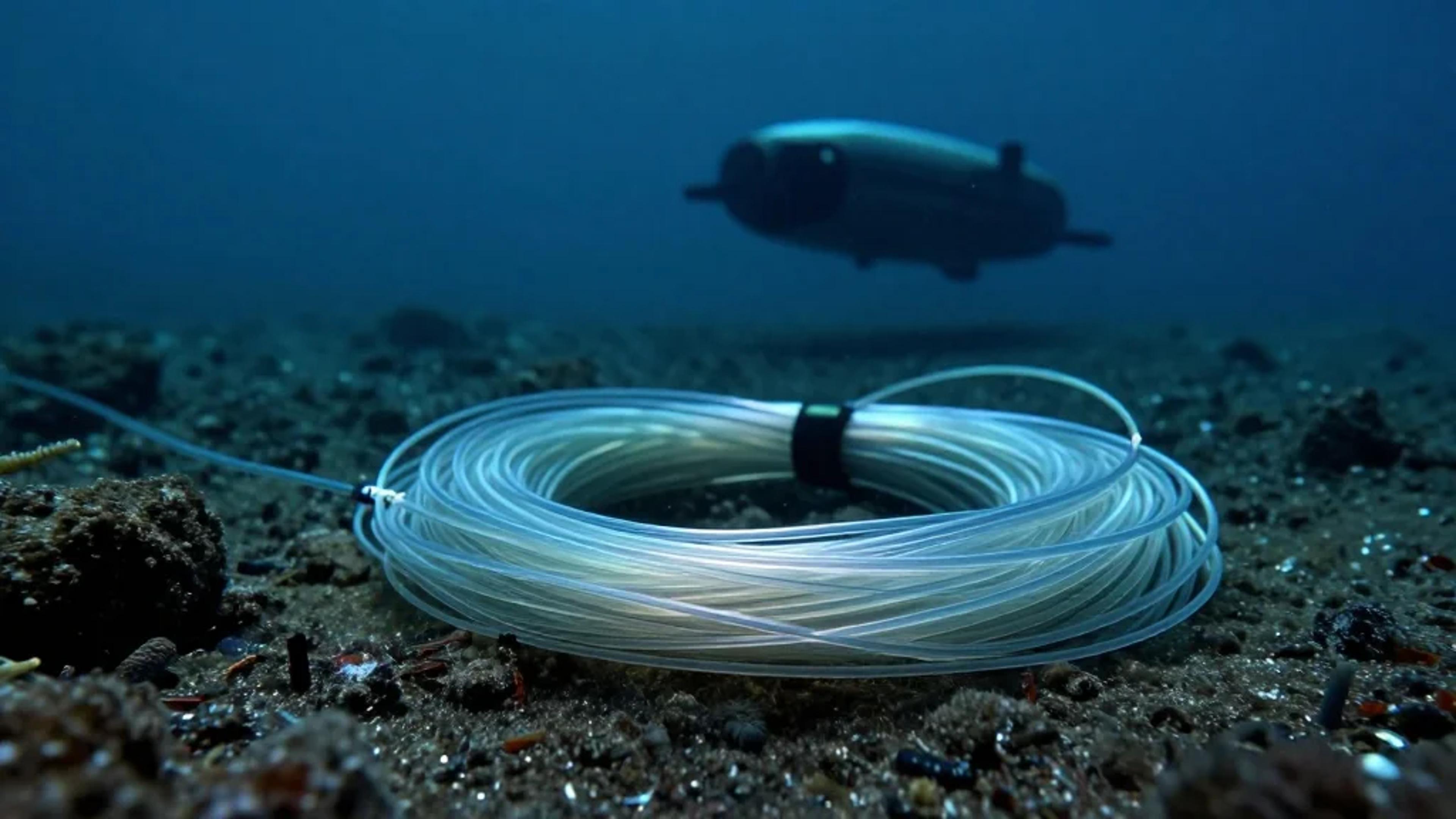

Uncrewed underwater systems, championed by the Atlantic Bastion vision, promise persistent surveillance but are hamstrung by fundamental physics. Power generation, endurance and reliable underwater communications remain unsolved challenges, as highlighted by the over‑budget, delayed US Orca XLUUV programme. Experts argue that autonomous platforms should augment, not replace, nuclear‑powered submarines, which retain unmatched stealth, data‑processing capacity and deterrence value. Simpler, tiered autonomous solutions may offer realistic gains without the cost overruns of ultra‑complex designs.

Despite these gaps, the UK retains distinct under‑sea strengths. Its Sonar 2076/2176 suites rank among the world’s best, and a decades‑long acoustic library provides unparalleled situational awareness in the North Atlantic and Arctic. Leveraging this data across NATO amplifies collective detection capabilities. However, sustaining hydrographic data collection, modernising legal frameworks and raising public understanding are essential to prevent the seabed from becoming an invisible battlefield that erodes national resilience.

UK faces rising undersea threat, MPs warned in stark evidence session

February 10 2026

At a special evidence session held today, the House of Commons Defence Select Committee examined growing threats to the UK in the under‑sea domain and considered what the response should be. It was an unusually strong session, with three highly experienced witnesses providing exceptional clarity on a subject that is often misunderstood or poorly explained.

The panel combined operational, industrial and academic perspectives. Commodore (Retd) John Aitken, now with Thales, drew on decades of RN submarine experience. Brett Phaneuf, Chief Executive of M Subs, spoke from the sharp end of building and operating uncrewed underwater systems. Professor Peter Roberts of Exeter University provided strategic context on how adversaries are using the seabed as part of wider grey‑zone pressure on the UK and its allies.

Cables, pipelines and the reality of the threat

Undersea cables featured prominently, with witnesses pushing back against both complacency and exaggeration. Around 120 international data cables connect to the UK, along with tens of thousands of kilometres of subsea infrastructure, carrying an enormous share of global trade and communications.

Cuts to cables are relatively easy in shallow waters and occur frequently due to accidents, but systems are generally resilient and repaired quickly. Tapping cables, by contrast, is technically complex and far harder to exploit at scale due to encryption and packetised data flows. The greater danger lies in disruption, coercion and signalling rather than espionage.

Professor Roberts warned that Russia’s approach is not about dramatic single acts but cumulative pressure. “They are not fighting a traditional war. They are striking infrastructure, resilience and political will, because that is how you weaken a society without crossing clear red lines.”

The session left little doubt that Russia remains the most acute under‑sea threat to the UK. Beyond its modern submarine fleet, the Russian navy operates a specialised deep‑sea organisation (GUGI) capable of working at depths no Western navy can routinely reach. Broadly speaking, Russia and China have invested in mass and unconventional means of under‑sea warfare, while Western navies have tended to build smaller numbers of conventional but exquisite underwater platforms.

Atlantic Bastion and the limits of autonomy

There are considerable reservations around the Atlantic Bastion concept, which aims to use networks of uncrewed systems to help secure the North Atlantic. While witnesses broadly supported the ambition, all three were clear that the idea exists mainly on PowerPoint, and many of the enablers required cannot be relied on using current technology.

Power generation, endurance and underwater communications remain fundamental constraints. Uncrewed systems cannot yet deliver the persistence, processing power or reliability implied by current rhetoric. As Brett Phaneuf bluntly put it, “It always comes back to power and communications. That is the basic limit imposed by the physics of the ocean.”

Phaneuf also noted that the USN’s high‑profile Orca extra‑large uncrewed underwater vehicle (XLUUV) programme is effectively failing, 64 % over budget, with Boeing withdrawing due to losses on a fixed‑price contract. This serves as a warning against pursuing overly ambitious, uncrewed submarines. The US tried to build a very high‑end, ocean‑crossing XLUUV capable of submerging to 6 000 metres, but it became too complex and too costly. Orca may never deliver a meaningful operational capability, reinforcing the case for simpler, cheaper, tiered options rather than a small number of exquisite platforms that promise too much and deliver too little.

Commodore Aitken agreed that uncrewed systems should supplement, not replace, crewed submarines. Nuclear‑powered boats remain the only platforms able to stay submerged indefinitely, process large volumes of data, communicate securely and impose credible deterrence. Without them, Atlantic Bastion risks becoming a thin tripwire rather than a robust defensive system.

Professor Roberts questioned whether blocking Russian access to the Atlantic should be such a priority if we can no longer rely on the US to provide troops, or at least weapons and supplies to Europe by sea in the event of war. This is a complex question, but despite efforts to become more self‑reliant, Europe will still rely on US‑made equipment for much of its military capability for many years to come. What makes more sense will be to push the Atlantic Bastion forward into the “Bear Gap”, bottling Russian naval forces up closer to their Kola Peninsula bases. This implies greater Arctic operating capabilities and the need for RN submarines to recover under‑ice operating skills.

Russian under‑ice operations and seabed‑operations expertise are areas where the UK has allowed skills to atrophy since the Cold War. Once Russian submarines reach the wider North Atlantic, they become extremely difficult to detect and track, placing a premium on operating further forward in the High North.

Even with a large budget and the might of Boeing behind it, the Orca XLUUV proved to be a technical over‑reach. The RN’s policy of building low‑cost technical demonstrator XLUUVs before investing too heavily in this complex technology is being vindicated.

UK strengths beneath the waves

Despite the many concerns, the session underlined some of the UK’s existing strengths in the under‑sea domain. The Sonar 2076 sensor fit carried by RN submarines was repeatedly described as among the best in the world, and its successor, Sonar 2176, is expected to retain or exceed current performance levels.

One less visible but critical asset is the UK’s oceanographic and acoustic knowledge base. The national library of underwater sounds collected by hydrographic vessels, submarines, seabed arrays and uncrewed systems over decades is probably the best in the world for North Atlantic and Arctic waters, enabling operators to distinguish normal background noise from hostile activity with far greater confidence. Shared with close allies, this data multiplies effectiveness across NATO.

The need for continued hydrographic Military Data Gathering effort must continue, and greater knowledge, even of our own under‑sea infrastructure, is also needed. Professor Roberts noted, “If we do not understand what our own seabed looks like in peacetime, we will not understand when somebody has interfered with it.”

Action this day

The most striking feature of the session was how clearly the witnesses articulated the stakes. Under‑sea threats are not theoretical. They directly affect electricity supplies, gas flows, financial transactions, communications and the UK’s ability to function as a modern state. Yet public and political awareness remains limited. Much of this activity is invisible, technically complex and deliberately deniable. That ambiguity works in an adversary’s favour. Serious disruption to under‑sea infrastructure would not even look like war, but its effects on daily life would be immediate and severe.

If there was a single message from the committee, it was that the under‑sea domain can no longer be treated as a niche naval concern. It is a frontline of national security. Without more sustained investment, legal reform and a more honest public conversation, the UK risks discovering the importance of the seabed only after it has already been exploited.

The full session is available on the committee’s YouTube channel.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...