Stop Overthinking and Choose the Simpler Answer: Occam’s Razor Explained

•February 10, 2026

0

Why It Matters

By prioritizing simplicity, leaders can cut analysis paralysis, allocate resources faster, and improve decision accuracy in fast‑moving markets.

Key Takeaways

- •Simpler explanation preferred when evidence equal

- •Overthinking stems from anxiety, ego, information overload

- •Apply checklist: identify facts, strip unverified assumptions

- •Not a substitute for proof; complexity needed if evidence demands

- •In business, it speeds decisions, reduces risk

Pulse Analysis

Occam’s Razor, a philosophical heuristic dating back to the 14th‑century monk William of Ockham, has become a cornerstone of modern problem‑solving. While scientists use it to prune theoretical models, executives apply the same logic to strategic planning, product roadmaps, and market analysis. By stripping away superfluous variables, teams can focus on core drivers, accelerating hypothesis testing and reducing the time spent on dead‑end ideas. This disciplined simplicity aligns with lean methodologies, reinforcing the value of evidence‑based choices over speculative conjecture.

Psychologically, humans gravitate toward elaborate explanations when faced with uncertainty. Anxiety fuels a need for control, ego rewards perceived intellectual depth, and information overload creates a patchwork of weak connections. These forces inflate narratives, leading to analysis paralysis and costly missteps. Recognizing these biases enables managers to counteract them, fostering a culture where data, not drama, guides conclusions. Training staff to ask, "What do we know for sure?" and "What assumptions remain unchecked?" cultivates sharper judgment and healthier risk tolerance.

In practice, the razor translates into actionable checklists across functions. Sales teams, for instance, might first assume a prospect’s silence reflects scheduling conflicts before attributing it to disinterest. Product engineers often test hardware failures by checking power sources before redesigning circuitry. Even boardrooms can benefit: when two strategic paths appear viable, the option requiring fewer new capabilities typically yields quicker ROI. Embedding this habit reduces waste, shortens cycles, and preserves organizational bandwidth for truly disruptive opportunities.

Stop Overthinking and Choose the Simpler Answer: Occam’s Razor Explained

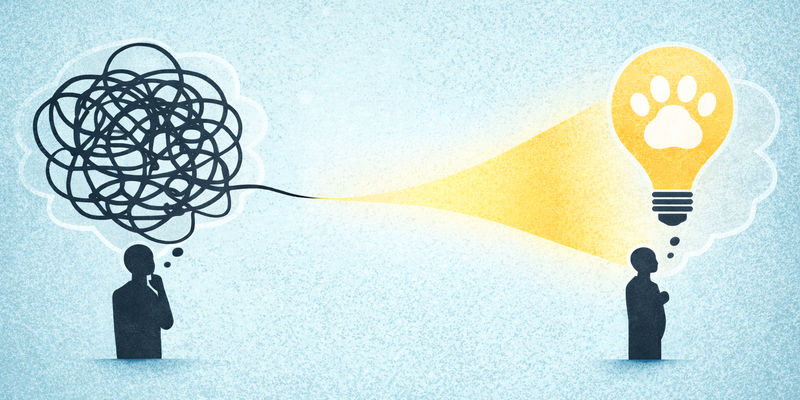

Occam’s Razor is one of those ideas that sounds obvious until you realise how rarely people follow it. Put simply, it argues that the simplest explanation that fits the facts is usually the best place to start. Not because the world is always simple, but because unnecessary complexity often comes from our own habits: overthinking, fear of being wrong, or the temptation to sound clever.

The principle is often paraphrased as: the easiest answer is often the right answer. That does not mean the first answer is always correct. It means you should not add extra assumptions when you do not need them.

What Occam’s Razor actually means

At its core, Occam’s Razor is a rule for reasoning. When you have two explanations that both match the evidence, prefer the one that makes fewer extra claims.

Consider the image in the prompt: you hear a meowing sound under the sofa. The simplest explanation is that the cat is under the sofa. A more complicated explanation is that a hidden speaker is playing a cat sound. Could that happen? Yes. Is it likely without other evidence? No.

The Razor is not saying “the cat is always under the sofa.” It is saying: start there. Check the obvious. Look for evidence. Only move to the unusual explanation if the simple one fails.

Why we complicate things

People often complicate their thinking for reasons that have nothing to do with logic.

One reason is anxiety. When something feels uncertain, the brain searches for control, and complex stories can feel like better preparation. Another reason is ego. A complicated explanation can make us feel more intelligent, even when it is less accurate. A third reason is information overload. When we have too many inputs, we build elaborate narratives to connect them, even if the connections are weak.

In everyday life, this shows up everywhere. A friend replies late, so we assume they are angry. A project misses a deadline, so we assume politics are at play. A minor health symptom appears, so we imagine the worst. Sometimes those complex explanations are true, but often they are just noise.

How to use Occam’s Razor in real life

Occam’s Razor becomes practical when you apply it as a checklist.

Start by asking: what is the simplest explanation that fits what I know for sure? Then ask: what assumptions am I adding that I have not verified?

If a client is silent, the simplest explanation might be that they are busy, not that they hate the work. If a device stops working, the simplest explanation might be a loose cable or low battery, not a major hardware failure. If a team member looks distracted, it might be fatigue, not disrespect.

This approach does not make you naive. It makes you efficient. You act based on what is most likely, while staying open to new evidence.

The “two hypotheses” rule

The classic phrasing captures the method well: “When faced with two equally good hypotheses, always choose the simpler.” The key words are “equally good.” If the evidence strongly supports the more complex explanation, Occam’s Razor does not apply. Simplicity is not a substitute for proof.

In journalism, for example, a simple explanation is not enough if facts point elsewhere. In science, a simple theory must still predict reality. In management, an easy answer must still survive scrutiny. The Razor is a starting point, not a verdict.

A useful discipline in a noisy world

Occam’s Razor is ultimately a discipline against mental clutter. It encourages you to check the obvious, reduce assumptions, and avoid building stories that outrun the evidence. In a time when people are surrounded by speculation, hot takes, and endless analysis, the ability to think simply is not simplistic. It is a form of clarity.

If you hear a meowing under the sofa, look for the cat first. If the cat is not there, then you can start looking for the speaker.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...