The $800B Open Secret: What the New Medicaid Spending Dataset Means for Health Tech Builders and Investors

•February 14, 2026

0

Why It Matters

Transparent, aggregated Medicaid claims data creates a rare window into a $800 B program plagued by billions in waste, enabling innovators to build more effective fraud‑prevention tools and drive cost savings for states and taxpayers. As digital‑health investment surges, the dataset lowers entry barriers, making the market ripe for new ventures that can outpace legacy incumbents and improve health‑system accountability.

The $800B Open Secret: What the New Medicaid Spending Dataset Means for Health Tech Builders and Investors

Table of Contents

What Actually Dropped Today (and Why It Matters)

The Dataset Itself: What’s in It, What’s Missing, What’s Useful

The Problem Space in Numbers

The Incumbent Landscape and Its Structural Weaknesses

Where the Venture Opportunity Actually Lives

Watch-Outs, Political Risk, and Things That Could Go Wrong

So What Do You Actually Do With This?

Abstract

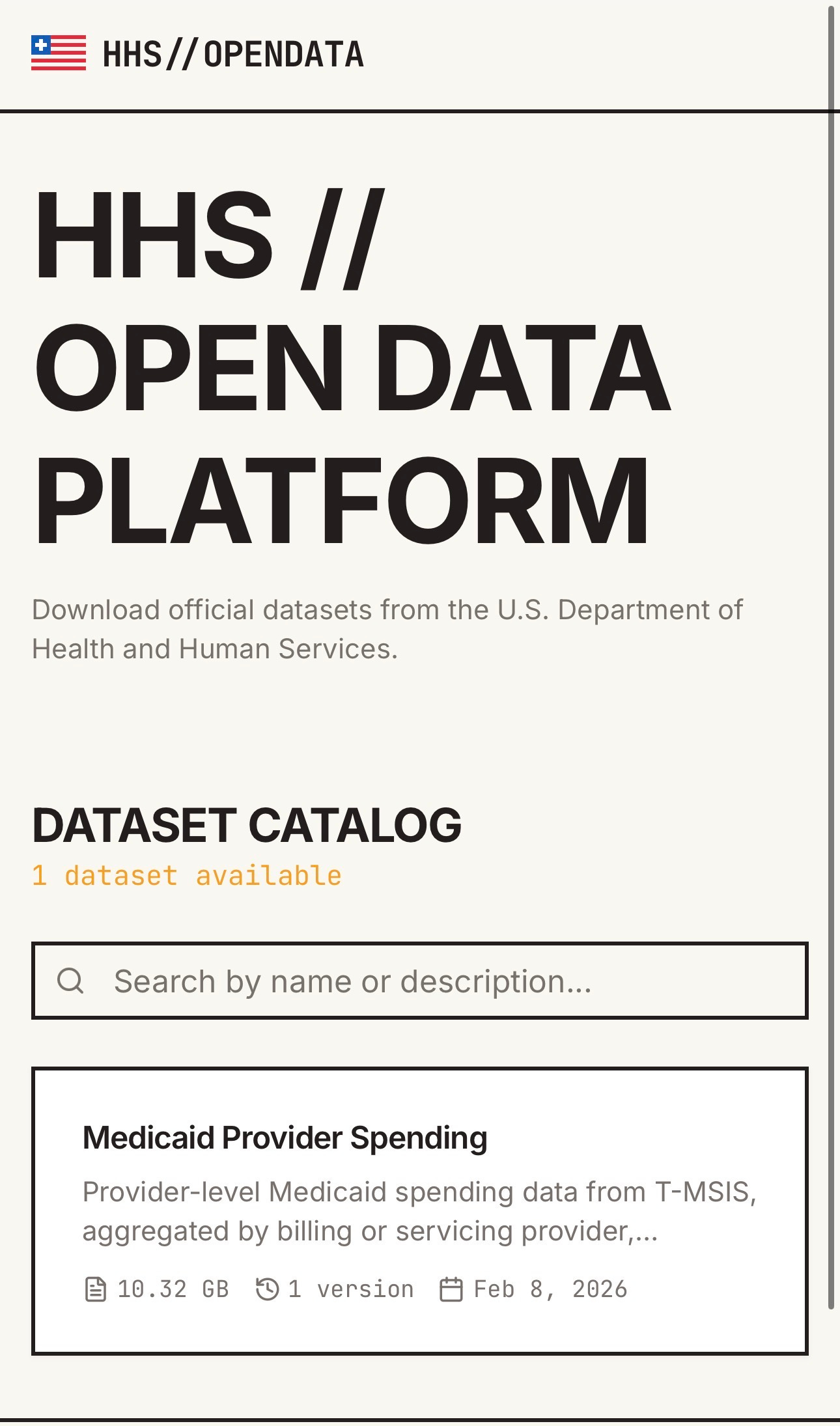

- On February 13, 2026, DOGE’s HHS team published what it’s calling the largest Medicaid claims dataset ever made publicly available, accessible at opendata.hhs.gov(http://opendata.hhs.gov)

- Medicaid total program spend: ~$849B (federal + state) in 2023, serving ~90M enrollees

- Medicaid improper payments: estimated $31.1B in FY2024 (5.09% improper payment rate per CMS), with some estimates going 3-4x higher when eligibility errors are included

- GAO estimated $100B+ in combined Medicare/Medicaid improper payments in FY2023

- The underlying T-MSIS (Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System) data covers 4 claims file types: inpatient, long-term care, other, and prescription

- DOJ’s 2025 healthcare fraud takedown charged 324 defendants for $14.6B in alleged fraud

- Digital health VC hit $12.3B in 2025 (PitchBook Q3 annualized), with payment integrity specifically getting PE consolidation attention

- This essay argues the public release is a genuine inflection point for a cluster of health tech use cases, and tries to map where the real build-vs-buy-vs-partner opportunities exist

-----

What Actually Dropped Today (and Why It Matters)

Medicaid data has historically been one of the most fragmented, hardest-to-access, least standardized bodies of administrative information in all of American healthcare. Fifty-one state programs, each with their own eligibility rules, managed care contract structures, fee schedules, and reporting formats. CMS has been collecting T-MSIS data from states since the mid-2010s, and even the research-accessible version (the TAF, or T-MSIS Analytic Files) required a CMS Privacy Board approval process and a data use agreement that could take the better part of a year for academic researchers, to say nothing of what it meant for commercial operators. The de-identified, aggregated public version that existed before today was useful for high-level trend analysis and not much else.

What DOGE’s HHS team dropped today is a different animal. HHS spokesperson Andrew Nixon described it as the first time the department is “expanding public access to de-identified, aggregated data to increase transparency and accountability beyond what is currently available.” DOGE itself announced this as the largest Medicaid claims dataset in department history. The context for the release is overtly political - the same announcement mentioned that the tool “could have helped detect large-scale autism diagnosis fraud in Minnesota,” a reference to a scandal that’s been a DOGE talking point for months - but the underlying data is real, it’s publicly downloadable, and it covers provider-level spending patterns across Medicaid in a way that hasn’t been available before.

For investors and builders, the politics are a sideshow. The data is the story.

To understand why, you need a quick refresher on how Medicaid data has worked historically. States submit claims data to CMS through the T-MSIS system, which includes four claims file types covering inpatient, long-term care, other services, and prescription drugs, plus a financial transactions file and beneficiary eligibility data. CMS runs over 6,000 data quality checks on state submissions. The resulting dataset is massive, with all 50 states (and DC, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands) reporting. But the version accessible to researchers and policy shops has always required institutional approval, been restricted to academic use, lagged 18-24 months behind real time, and been structured in a way that made commercial product development extremely cumbersome. The new open data portal cuts a layer of that friction.

The specific dataset published today focuses on provider-level spending patterns - essentially, what individual Medicaid providers are billing, in aggregate, across states. That’s the table stakes version of the data that fraud investigators have always wanted but haven’t had easy public access to. The implications of that shift are not small.

The Dataset Itself: What’s in It, What’s Missing, What’s Useful

Before anyone gets too excited and starts building product roadmaps on a Friday afternoon, it’s worth being specific about what the data actually is and isn’t.

On the positive side: provider-level Medicaid spending aggregated across states in a publicly downloadable format is genuinely novel. The T-MSIS underlying source data is more granular than anything previously available through public channels. For the first time, someone with a laptop and some Python can start asking questions like which NPI numbers are in the top billing percentiles for specific procedure codes in specific states, how provider spending patterns compare across Medicaid programs with different managed care penetration rates, and where outliers cluster by geography, specialty, and service category. That’s a meaningful starting point for anomaly detection, peer benchmarking, network adequacy analysis, and a bunch of other downstream applications.

On the limitations side: a few things to keep in mind. First, this is de-identified and aggregated - you’re not getting beneficiary-level claims files here, which means use cases that require patient-level longitudinal analysis still require the full T-MSIS TAF research files and the DUA process. Second, the data quality across states varies significantly. CMS’s own OBA (Outcomes Based Assessment) framework applies more than 600 high and critical priority data quality checks, and state performance on those checks is publicly tracked. Some states have meaningful data completeness and accuracy gaps, particularly in managed care encounter data, which in many states represents the majority of Medicaid spending. Third, the data still lags real-time operations by design - this is administrative claims data, and the pipeline from state submission to public availability introduces delay. Fourth, and this is subtle but important: about two-thirds of Medicaid spending nationally now flows through managed care organizations (MCOs), and the quality of encounter data submitted by MCOs varies dramatically. A state where MCO encounter data is sparse or incomplete will show misleadingly low apparent provider spending.

None of those limitations make the dataset not useful. They make it a starting point rather than a finished product. The people who will extract the most value from it are the ones who understand those limitations deeply enough to account for them in product design, and who can combine the public data with proprietary signals to fill the gaps.

The most immediately useful applications of the new dataset in roughly decreasing order of data quality dependency: provider outlier identification for fraud investigation (high data quality needed, but lots of signal in the aggregate even with gaps), peer benchmarking for state Medicaid agencies and MCOs (moderate quality needs, relative comparisons are more robust than absolute ones), network adequacy and access analytics for managed care plans (lower quality sensitivity, directionally useful even with gaps), policy analysis and advocacy (the broadest and most forgiving use case, where trends matter more than precision), and market intelligence for health tech vendors trying to understand where Medicaid spending concentrates by geography and specialty.

The Problem Space in Numbers

Let’s ground this in why the problem is interesting enough to build for and invest in.

Medicaid is the second-largest health program by expenditure in the US. Total federal and state Medicaid spending hit approximately $849B in 2023 for roughly 90 million enrollees. That number has been growing faster than CMS projected throughout the 2020s, driven by a combination of the ACA expansion, pandemic-era continuous enrollment policies, increased per-enrollee spending, higher drug costs, greater use of long-term services and supports, and state-directed payment mechanisms. Even as COVID-era enrollment unwinding reduced beneficiary counts modestly in 2024 and 2025, per-enrollee spending kept climbing.

Improper payments are where the product opportunity crystallizes. CMS’s official estimate for Medicaid improper payments in FY2024 was $31.1B, representing a 5.09% improper payment rate. That’s the number HHS puts in its annual financial report. It’s also probably conservative. The Payment Error Rate Measurement (PERM) program that CMS uses to calculate that figure has historically excluded eligibility errors from its calculation, and when researchers at the Paragon Institute applied a broader methodology that included eligibility verification, the estimated cumulative improper Medicaid payments from 2015-2024 came out around $1.1 trillion, roughly double GAO’s $543B estimate for the same period. The debate about the right methodology is real and ongoing, but even at the conservative official number, $31.1B a year in improper payments on an $849B program is a massive problem with an obvious technology component.

Beyond pure fraud, there are structural inefficiencies that are arguably bigger in aggregate. The $51B in Medicare improper payments and $50B in Medicaid improper payments that GAO flagged for FY2023 are just the identifiable surface. The DOJ’s 2025 National Health Care Fraud Takedown, the largest in US history, resulted in criminal charges against 324 defendants for schemes involving over $14.6B in intended loss. Operation Gold Rush alone, targeting a transnational criminal organization running multi-billion-dollar Medicare schemes, illustrated how sophisticated and organized the fraud ecosystem has become.

State-to-state variation is another piece of the picture that the new dataset should illuminate. KFF’s analysis of T-MSIS data shows that Medicaid spending per enrollee varies by a factor of more than 3x across states, even controlling for eligibility group. An aged, blind, and disabled enrollee in New York costs about $30,000/year in Medicaid, while a similar enrollee in Texas costs closer to $12,000. Some of that reflects legitimate differences in benefit design, provider rates, and local cost-of-care. Some of it reflects differences in managed care penetration, administrative rigor, and fraud control effectiveness. A dataset that lets analysts start decomposing those differences at the provider level is genuinely useful for policymakers, MCO executives, and any vendor trying to understand where they can add value in specific state markets.

The specific Minnesota autism fraud case that DOGE keeps referencing is worth understanding on its own terms as a case study. The allegation, which the US Attorney for Minnesota flagged as potentially involving upwards of $9B in losses over recent years, centered on providers paying parents to have children diagnosed with autism specifically to maximize Medicaid billing. The scheme was allegedly detectable through billing pattern anomalies that would have been visible in provider-level claims data had that data been more readily available and analyzed. Whether or not DOGE’s characterization of that case is accurate in its specifics, the structural vulnerability it illustrates is real: when a provider-level billing outlier can persist for years across a multi-billion-dollar program because no one has easy visibility into cross-state spending patterns, that’s a data availability problem as much as it’s a human oversight problem.

The Incumbent Landscape and Its Structural Weaknesses

The healthcare fraud and waste detection market has been around for decades, which is part of the problem. The current ecosystem is dominated by legacy players whose products were built in a different era of data availability, computing capability, and healthcare program structure.

Cotiviti, Optum (through its Clinical Intelligence and payment integrity units), Change Healthcare (now part of UnitedHealth’s Optum stack), and a collection of smaller regional firms like Conduent and NCI Information Systems have historically held most of the large Medicaid and Medicare payment integrity contracts. These are not small businesses - Cotiviti processes billions of dollars in claims reviews annually, and Optum’s analytics business generates billions in revenue. But their core products were designed around rule-based retrospective auditing: you build a library of billing code combinations that are known fraud patterns, you run claims through those rules after payment, you identify recoveries, and you take a percentage of what you recover. It’s a useful capability and it will always have a role, but its limitations are well understood.

Rule-based systems are inherently reactive. They can only catch fraud patterns that someone has already documented and codified. A sophisticated operator who stays just outside the known rule violations can extract enormous value for years without triggering anything. The autism case in Minnesota is a good example of exactly this failure mode. The billing patterns were anomalous in a way that would have been obvious to any unsupervised learning model looking for outliers - providers with rapid enrollment growth, high per-beneficiary billing, claims concentrated in procedure codes with weak documentation requirements, unusual geographic clustering - but those aren’t the kinds of patterns rule-based systems are designed to catch proactively.

The other structural weakness of the incumbent landscape is its dependence on proprietary data silos. A firm like Cotiviti gets its advantage partly from having accumulated benchmarks across many client programs - essentially, a private claims database that lets them flag statistical outliers. But those benchmarks are siloed within their client relationships and are not refreshed at anything close to real-time. The T-MSIS data that was available to them was subject to the same access constraints and data quality issues that affected everyone else.

In 2025, New Mountain Capital made a significant PE bet on the consolidation thesis, acquiring Machinify and combining its AI capabilities with legacy payment integrity providers including Apixio, Varis, and The Rawlings Group into a combined entity. The bet is essentially that combining established distribution (relationships with MCOs and state Medicaid agencies) with modern ML infrastructure creates a more defensible business than either could build alone. That’s probably right as far as it goes, and it signals that smart money sees the space as ripe for AI-native disruption, even if the PE approach is more roll-up than greenfield innovation.

The gap being created here, and where the venture-scale opportunity lives, is in the combination of three things that the incumbents structurally can’t provide: real-time or near-real-time anomaly detection using modern ML on the new public data combined with proprietary signals, workflow tools that actually integrate into state Medicaid agency and MCO operating environments in a way that creates stickiness, and the ability to move quickly as new fraud patterns emerge rather than waiting for a rules library to be updated.

Where the Venture Opportunity Actually Lives

The new dataset is useful, but it’s a raw ingredient. The venture-scale businesses get built on top of infrastructure that transforms that ingredient into defensible, recurring products. Here’s an honest map of where the opportunity clusters.

The most direct application is Medicaid-specific payment integrity SaaS. The market has historically been dominated by the incumbents described above, operating under contingency-fee audit contracts (typically 10-30% of recovered dollars) or flat-fee managed care subcontracts. The contingency-fee model creates weird incentives: auditors go after the lowest-hanging, easiest-to-document patterns because the economics of chasing sophisticated fraud are worse. A SaaS model that charges state Medicaid agencies or MCOs a platform fee for continuous monitoring rather than a percentage of recoveries aligns incentives better and creates more predictable revenue. The challenge is that state Medicaid agency procurement is slow, relationships matter a lot, and the switching costs from incumbents are real. But the market is large enough that even a narrow wedge is interesting - a state like California with $140B+ in annual Medicaid spending can justify paying real money for a meaningfully better tool.

The second cluster is what you might call Medicaid market intelligence for health tech vendors and health plans. This one is underappreciated. Any company selling technology or services into the Medicaid ecosystem (and that’s a lot of companies - EHR vendors, RCM companies, managed care tech platforms, pharmacy benefit managers, home health operators) needs to understand how Medicaid spending is distributed across states, specialties, and service categories to allocate their sales resources intelligently. The public dataset creates a foundation for commercial intelligence products that are analogous to what companies like Symphony Health or IQVIA have built for the pharmaceutical industry - essentially, turning claims data into market maps that help operators make better go-to-market decisions. This is a faster-moving, lower-regulatory-barrier opportunity than the payment integrity space.

Network adequacy analytics is a third use case that doesn’t get enough attention. Federal managed care regulations require MCOs with Medicaid contracts to demonstrate that they have sufficient providers in their networks to serve enrollees within time and distance standards. Compliance with those requirements is monitored by state Medicaid agencies, but the monitoring tools have historically been inadequate. Provider-level Medicaid spending data, combined with geographic and specialty information, creates a much richer basis for network adequacy modeling than what’s existed before. This is interesting not just as a compliance tool but as a strategic asset for MCOs figuring out where to invest in network development.

The fourth area is genuinely underserved and potentially the largest: beneficiary navigation and enrollment integrity. About 77 million people were enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP as of September 2025. The “unwinding” of pandemic-era continuous enrollment policies in 2023 and 2024 resulted in millions of eligible people losing coverage due to administrative failures rather than actual ineligibility changes. Meanwhile, the new OBBBA budget reconciliation package signed on July 4, 2025 introduced Medicaid work requirements and other eligibility changes that will create new administrative complexity at scale. The combination of more complex eligibility rules, more frequent redeterminations, and a data asset that can help identify where eligibility mismatches are occurring is a real product opportunity. Fortuna, a YC-backed startup, is going after part of this with an end-to-end Medicaid navigation platform - the concept is right even if the execution is early.

The fifth cluster is public health and policy analytics, which is more consulting-adjacent than pure SaaS but shouldn’t be dismissed. State health departments, advocacy organizations, academic medical centers, and a growing number of large health systems want analytical capabilities that let them work with Medicaid data at scale. The new public dataset, combined with other open data assets (Census, HRSA, AHRQ, OpenPayments), creates a rich substrate for these kinds of analyses. A platform that makes it easy for less technical users to query and visualize this data - think Palantir-lite for Medicaid analysts - has a real market, even if the buyer profile (state agencies, health systems, foundations) makes it a slower sale than a purely commercial customer.

Watch-Outs, Political Risk, and Things That Could Go Wrong

None of this is risk-free, and some of the risks are non-obvious, so they’re worth naming directly.

The biggest single risk is political instability of the data asset itself. This dataset was released by DOGE’s HHS team as part of a politically motivated narrative about fraud in Medicaid. Administrations change, political priorities shift, and data that was made public can be made less accessible, less maintained, or simply deprecated in a future administration. The T-MSIS program itself depends on continued CMS funding and state cooperation. DOGE has simultaneously been cutting CMS staff and budget in other areas, which creates a tension: the agency being asked to publish and maintain better data is also the agency being stripped of the capacity to do it well. Founders building product on this dataset need a data diversification strategy that doesn’t make them entirely dependent on continued government openness.

The data quality issue is both a risk and an opportunity, but it tilts toward risk at the product design level. The T-MSIS OBA framework tracks state performance on over 600 high and critical data quality checks, and a meaningful number of states have persistent gaps, particularly in managed care encounter data. A product that uses the public dataset without explicitly accounting for state-level data quality variation will produce systematically biased outputs. In managed care states with poor encounter data submission - and there are several large ones - the spending patterns visible in the dataset may reflect the quality of reporting infrastructure as much as they reflect actual care delivery patterns. Any ML model trained on the raw data without state-level quality weights will find the quality artifacts as reliably as it finds the fraud signals.

Privacy risk is real even with de-identified, aggregated data. There’s a well-documented academic literature on re-identification attacks on aggregated healthcare data, particularly when geographic and demographic cut-points are fine enough. HIPAA’s de-identification standards were written in a different era of data availability, and the combination of the new Medicaid dataset with other publicly available data sources (OpenPayments, NPPES, provider directories, social media) creates re-identification vectors that weren’t contemplated when the data was designed. Vendors building on this data need to be thoughtful about what they aggregate and at what granularity, not just because of legal risk but because a high-profile re-identification incident would generate regulatory blowback that could constrain the entire space.

The incumbent response is also worth modeling. Cotiviti and Optum are not going to ignore a new public data asset that could theoretically commoditize part of their business. They have the relationships with state Medicaid agencies, the existing contracts, and the resources to build or acquire the ML capabilities to compete on the new data. The venture window here is probably 18-36 months before the large incumbents have incorporated the public dataset into their products in a way that narrows the differentiation available to startups. That’s enough time to build and scale something interesting, but it’s not infinite, and the sales cycle for selling into state Medicaid agencies is long enough that the clock matters.

Finally, there’s the OBBBA policy risk. The reconciliation package Trump signed on July 4, 2025 cuts nearly $1 trillion from Medicaid over the next decade, introduces work requirements for expansion enrollees, restricts state-directed payment mechanisms, and limits provider tax financing arrangements that many states use to increase their federal matching dollars. MedPAC and CBO both projected the bill will reduce Medicaid enrollment by more than 10 million people. A significantly smaller Medicaid program means a smaller total addressable market for Medicaid-focused products, and the states most affected by the cuts are also the states that often have the most interesting data and the most sophisticated MCO infrastructure. This is a macro headwind for the space that any investor or founder needs to think through carefully - the opportunity is real, but it’s operating inside a program that is under genuine political pressure to shrink.

So What Do You Actually Do With This?

For investors with existing portfolio exposure to payment integrity, RCM, or healthcare data infrastructure, the dataset release is a forcing function to re-underwrite competitive positioning. Any company in those categories whose defensibility depends on proprietary access to data that just became significantly more available has a potential moat problem. The conversation to have with those portfolio companies this week is not “how do you use the new data” but “how does this change the competitive landscape for your core product.”

For investors evaluating new opportunities, the dataset creates a few categories worth accelerating diligence on. Medicaid-specific AI/ML payment integrity platforms with real state agency relationships, strong data quality handling, and defensible IP beyond the public data are worth a serious look, particularly if they’ve been quietly building for a few years and have production deployments. Be skeptical of pitches that lean heavily on “we have access to the new public Medicaid data” as a core differentiator - everyone has that access now, and the moat has to be in what you do with it. The real moat candidates are companies with proprietary labeled datasets of confirmed fraud outcomes (because that’s what lets you train a discriminative model that’s actually useful), and companies with deep workflow integration into state or MCO operating environments.

For founders thinking about the space, the product insight that matters is that the public dataset is most useful as a seed layer for building something proprietary. The pattern is roughly: start with the public T-MSIS spending data to build a baseline anomaly detection model, use that model to generate leads that get investigated and confirmed (or not), turn those confirmed outcomes into labeled training data, train a better model on the labeled data, and use that better model to surface better leads. The value accumulates in the labeled dataset, not in the public data itself. That’s the flywheel, and the company that runs it fastest and most rigorously in a specific segment (say, behavioral health billing fraud in managed care, or durable medical equipment patterns in specific geographies) will build a compounding advantage that’s genuinely hard to replicate.

The broader point is that publicly available Medicaid data at provider-level resolution is a fundamentally new capability for the health tech ecosystem, even with all its caveats. The closest analog is probably the Open Payments (Sunshine Act) database that CMS has published since 2014, which tracks payments from pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers to physicians and teaching hospitals. That data release generated an entire ecosystem of compliance tools, investigative journalism, and policy analysis that didn’t exist before it. The Medicaid provider spending dataset is potentially more impactful because the underlying program is larger, the fraud problem is more acute, and the computational tools available for making sense of it are dramatically better than they were in 2014.

The question for anyone in this space is not whether the data matters. It does. The question is whether you have the specific combination of domain expertise, technical capability, state-level relationships, and data quality savvy to build something on top of it that compounds. That bar is higher than the announcement suggests, and that’s probably why the opportunity is real.

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pMDC!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8e7d5b01-4b29-46c9-9667-cd8f01df6471_1290x2190.jpeg)

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...