Lung Cancer Rising Among Never-Smokers. Screening For This Group Lags.

•February 17, 2026

0

Why It Matters

The case underscores a growing public‑health gap: high‑risk lung cancer is missed in never‑smokers, while early detection dramatically improves survival. Expanding evidence‑based screening could reduce mortality and address gender and socioeconomic disparities.

Key Takeaways

- •Lung cancer in never‑smokers now 10‑20% of US cases

- •Current USPSTF screening excludes most never‑smokers

- •Whole‑body MRI detects incidental nodules, low cancer yield

- •Early CT follow‑up enabled curative surgery for stage I disease

- •Equity barriers limit access to advanced screening for many

Pulse Analysis

The rise of lung cancer among never‑smokers is reshaping oncologic epidemiology. While smoking remains the dominant risk factor, 10‑20% of U.S. cases now occur in individuals without a tobacco history, often presenting as EGFR‑mutated adenocarcinoma. This biologic shift challenges the traditional perception of lung cancer as a smoker’s disease and raises questions about the adequacy of risk‑based screening models that rely solely on pack‑year calculations. As environmental pollutants, radon exposure, and genetic susceptibility gain recognition, policymakers and clinicians must consider broader criteria to capture at‑risk populations before symptoms emerge.

Low‑dose CT (LDCT) is the only modality with proven mortality benefit, yet its eligibility thresholds exclude millions of never‑smokers, disproportionately women and younger adults. Whole‑body MRI offers radiation‑free, whole‑organ surveillance, but data reveal a modest cancer detection rate—approximately 1 % of exams result in a confirmed malignancy—while generating numerous incidental findings that can trigger costly work‑ups and patient anxiety. The Boehler case illustrates the ideal cascade: an MRI flag, a targeted CT confirmation, and curative surgery. However, the broader evidence base suggests that routine WB‑MRI for asymptomatic individuals may not be cost‑effective without clear risk stratification and radiologist expertise.

To bridge the gap between early detection and equitable access, health systems should invest in expanded LDCT programs that incorporate non‑smoking risk factors such as occupational exposures, family history, and genomic markers. Parallelly, insurance coverage for follow‑up imaging and multidisciplinary care pathways can mitigate the financial barriers highlighted by Boehler’s experience. By aligning screening policy with emerging epidemiology and ensuring that advanced imaging is deployed responsibly, the industry can improve outcomes for never‑smokers while avoiding overdiagnosis and unnecessary interventions.

Lung Cancer Rising Among Never-Smokers. Screening For This Group Lags.

Shira Boehler

At 43, Shira Boehler considered herself healthy. She had never smoked. She exercised regularly, avoided ultra‑processed foods, and attended routine medical appointments. So when her husband suggested she get an elective full‑body screening whole‑body MRI, she hesitated. “I had no symptoms,” she said, “and no family history of cancer.” Still, with convincing from her spouse, she agreed.

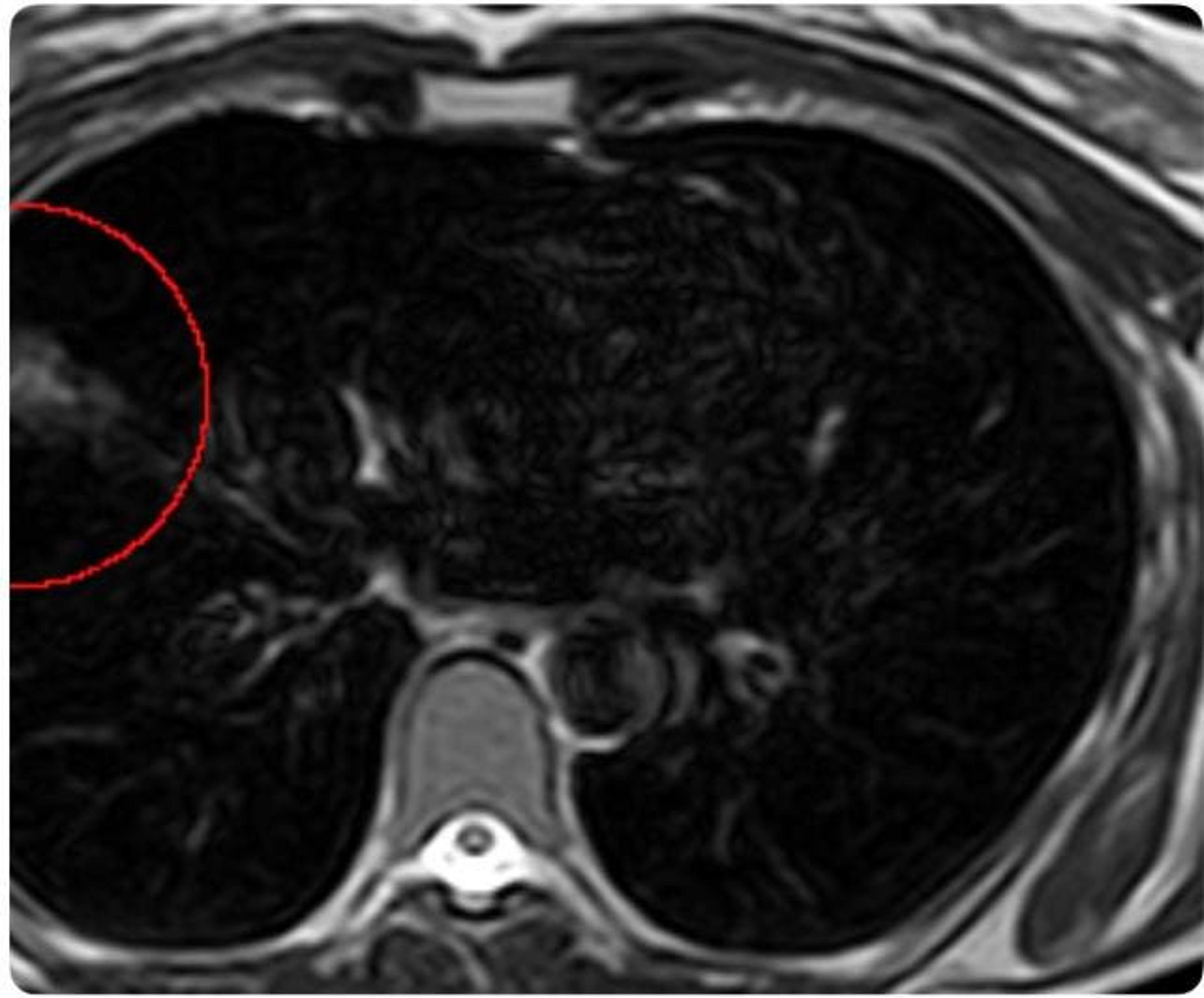

Her WB‑MRI noted an abnormality in the right lung measuring approximately 3.8 cm. The finding was described in the report as “minor,” “non‑urgent,” and “typically harmless.” At the bottom was a recommendation: consider a follow‑up CT scan in three months. She left with the impression that nothing was urgent or alarming.

Later, she mentioned the WB‑MRI finding to her friend, a radiologist. The friend suggested a more sensitive test, a CT scan, to better characterize the area. While MRI is equipped to detect larger pulmonary nodules, CT imaging remains the gold standard for lung cancer screening because of its superior ability to detect and define nodules, particularly smaller nodules. The added clarity from the CT proved beneficial as it told a more concerning story for Boehler. The lesion previously seen on WB‑MRI was growing.

A biopsy and additional imaging confirmed the diagnosis: Stage I adenocarcinoma, an early‑stage non‑small cell lung cancer. She had no symptoms or traditional risk factors that would have led her, or her doctors, to anticipate disease.

The Rise of Lung Cancer in Never‑Smokers

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. In the United States alone, it will claim over 125,000 lives in 2026. While the total number of lung cancer cases is decreasing, the proportion of cases in never‑smokers is rising. Ten to twenty percent of lung cancers in the U.S. occur in people who have never smoked.

The cancer biology often differs for never‑smokers. Never‑smokers are more likely to develop adenocarcinoma, the subtype Boehler had, and are more likely to harbor specific genomic alterations, such as mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene. These molecular features can guide targeted therapies and influence prognosis.

Screening guidelines in the United States remain largely tethered to smoking history. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends annual low‑dose CT screening for adults aged 50 to 80 with a significant active or prior smoking history. That policy is grounded in evidence: the National Lung Screening Trial demonstrated a 20 % reduction in lung‑cancer mortality with LDCT compared with chest X‑ray. However, participants in that study were heavy smokers and between 55‑74 years of age.

These national screening criteria exclude millions of people—disproportionately women and never‑smokers—who may still be at risk due to environmental exposures, radon, air pollution, genetic susceptibility, or factors we do not yet fully understand.

Treatment of Stage 1 Lung Cancer

Because Boehler’s tumor was caught at Stage I, her prognosis was fundamentally different from that of patients diagnosed with later stages. She underwent surgical resection—removal of the affected portion of her right lung. “My lymph nodes were clear. There was no evidence of metastasis,” she said.

For Stage I lung cancer, surgery alone can be curative, though not every patient is a candidate for surgery and some require additional treatments. When Stage I non‑small cell lung cancer is detected early and completely resected, five‑year survival often exceeds 70 % and may approach 90 % in selected patients. This stands in stark contrast to advanced stages, where treatment shifts to systemic therapy and survival declines substantially. The sharp change in prognosis across stages underscores the power of early detection—ideally before symptoms ever appear.

The Promise and Questions of Whole‑Body MRI

The scan that began Boehler’s diagnostic journey was performed through Prenuvo, a company offering WB‑MRI screening. Even though she wasn’t initially concerned about her reading, she believes, “that scan saved my life.” It started the cascade of further testing that she would have otherwise not done. She fears that without the WB‑MRI she would have been diagnosed only when symptoms developed.

Unlike CT scans, WB‑MRI uses magnetic fields and radiofrequency waves, not ionizing radiation. That makes it appealing for individuals seeking broad surveillance without radiation exposure. Dr. Daniel Durand, CMO of Prenuvo, says the company’s goal is to offer proactive health assessment, “capable of detecting early cancers as well as aneurysms, liver disease, and other structural abnormalities.”

Whole‑body MRI is not new. It has established roles in high‑risk populations, such as patients with hereditary cancer syndromes. Though data show some benefit to screening WB‑MRI in asymptomatic patients, some physician experts urge caution. A 2020 study reviewing 12 prior WB‑MRI screening studies in asymptomatic patients found that across 11 studies and 5,233 exams, 1.8 % were initially reported as positive for malignancy, but among 10 studies that confirmed cancers, only 1.1 % of 3,692 exams were ultimately diagnosed as malignant. Authors urged caution with WB‑MRI readings by radiologists not trained in oncology and emphasized discussing upfront with patients the limitations of the test and risks from exploring incidental findings.

That dual reality—early detection alongside incidental findings—drives the debate. False positives can trigger anxiety, additional imaging, biopsies, and costs. Biopsies are not benign; lung‑nodule biopsies alone carry a 15‑40 % complication rate.

While I believe cancer screening should be more aggressive for young adults, caution against overuse of WB‑MRI is fair and often highlights the systemic need for anxiety management, lifestyle interventions, and patient understanding of procedural risks, such as biopsies. However, cases like Boehler’s show the scan can uncover potentially lethal pathology that would otherwise go undetected.

Equitable Screening at Scale for Lung Cancer

Boehler’s diagnosis challenges the persistent stigma that lung cancer is solely a smoker’s disease. It also raises a difficult but necessary question: how do we balance the benefits of early detection with the risks of overdiagnosis and overtreatment?

There is no single solution. Low‑dose CT remains the only modality proven to reduce lung‑cancer mortality in high‑risk populations. Whole‑body MRI, as offered by companies like Prenuvo, represents an emerging frontier with the potential to expedite detection—particularly when integrated into a care plan developed with a primary‑care physician, ensuring appropriate interpretation and timely follow‑up or reassurance of any findings.

For Boehler, the equation was simple: MRI led to CT, CT led to surgery, and surgery led to survival. The challenge now is determining how others might benefit—and how to do so responsibly, equitably, and guided by evidence rather than fear.

Boehler’s story is inspiring, especially her efforts to move from a patient with cancer to an advocate for others. She is speaking out on social media and has documented her journey in a book. But she realizes that her journey is not universally replicable. “I could afford a full‑body MRI, follow‑up CT, and specialty care,” she said. She also had physicians in her network to interpret results and expedite testing, and surgery at a high‑level center. Most Americans lack these advantages: they face cost barriers, delays for specialty appointments, and fragmented systems without insider knowledge.

If early detection is to move beyond a concierge experience, we must expand evidence‑based screening, invest in equitable imaging infrastructure, reduce out‑of‑pocket costs, and build care models that ensure cancer detection is not left to chance or privilege.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...