Startup Organotics Fast Tracks Personalized Brain Drug Trials

•February 13, 2026

0

Why It Matters

The approach could slash billions lost to late‑stage failures while delivering truly personalized therapies for disorders like autism, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

Key Takeaways

- •Patient-derived organoids mimic human brain circuitry

- •Scalable production enables high-throughput drug screening

- •AI integration aims to predict responses without organoids

- •Targets 96% failure rate in neuropsychiatric drugs

- •Could personalize treatment for autism, schizophrenia, bipolar

Pulse Analysis

The pharmaceutical industry faces a staggering 96% failure rate for neuropsychiatric drugs, a problem rooted in the limited translatability of animal models. Traditional mouse studies cannot capture the intricate human neural circuits, immune interactions, and developmental timelines that drive conditions such as autism, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. This translational gap inflates development costs and delays access to effective therapies, prompting a search for human‑relevant platforms that can de‑risk pipelines earlier in the process.

Organotics addresses this gap by producing patient‑specific brain organoids that combine cortical, midbrain, and hindbrain regions with self‑assembled blood vessels and microglia. The technology’s scalability—hundreds of organoids per individual—allows pharmaceutical companies to run high‑throughput screens directly on human‑adjacent tissue, dramatically shortening the pre‑clinical timeline. In parallel, the startup is partnering with MIT’s computational biology group to layer AI‑driven pattern recognition on organoid data, aiming to forecast drug efficacy from clinical histories alone. This hybrid of wet‑lab precision and digital analytics promises a more nuanced stratification of heterogeneous patient populations.

If successful, Organotics could reshape capital allocation in psychiatric drug development, turning billions of dollars of late‑stage risk into earlier, data‑rich decisions. The model also opens pathways for personalized treatment plans, where clinicians could select therapies based on a patient’s organoid response profile. While challenges remain—standardizing organoid production at scale and validating AI predictions—the convergence of stem‑cell biology, bioengineering, and machine learning positions Organotics at the forefront of a potential paradigm shift in neuropsychiatric care.

Startup Organotics Fast Tracks Personalized Brain Drug Trials

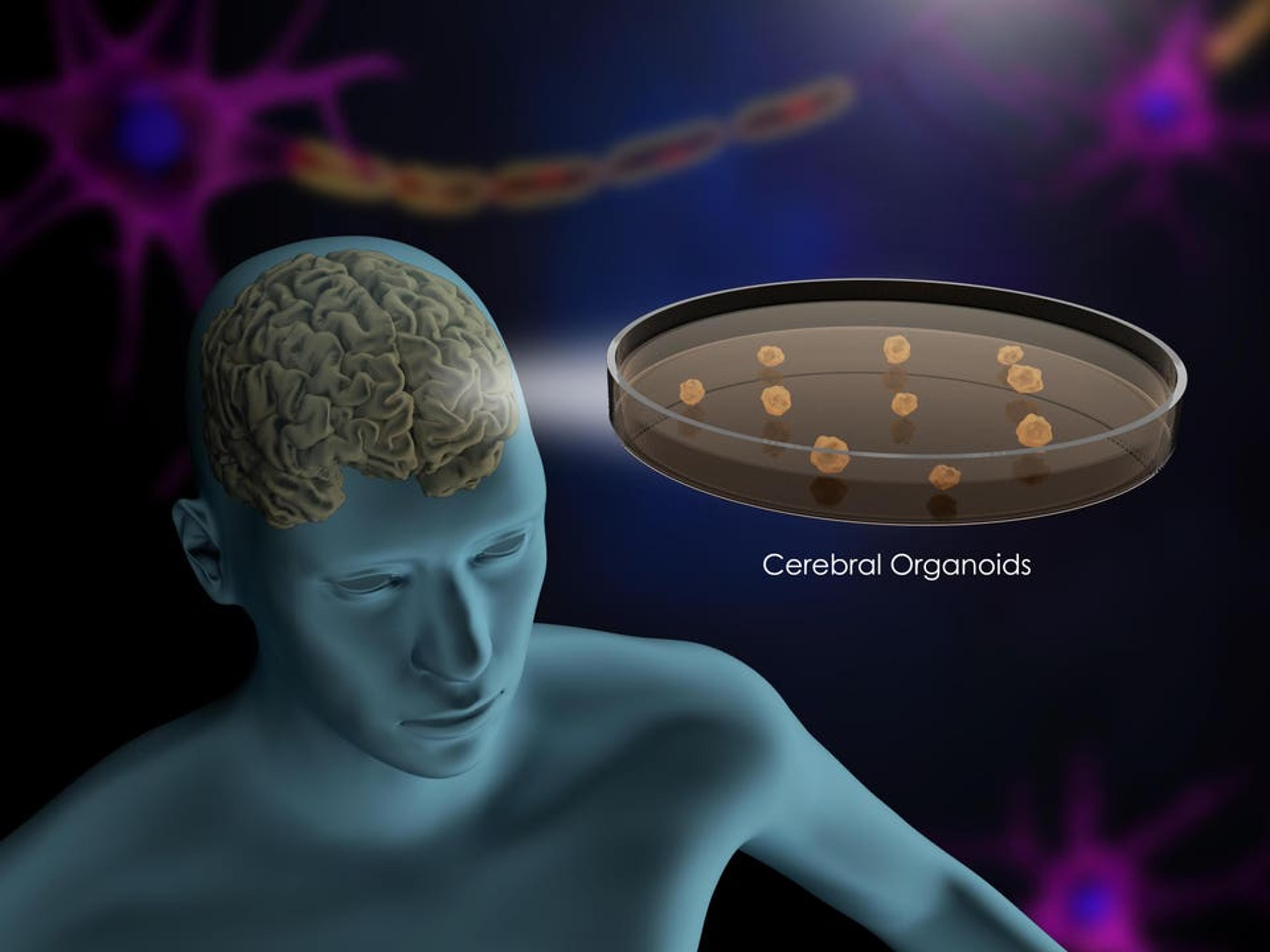

Image: Cerebral organoids in a petri dish

Psychiatric drug development has a sobering statistic: nearly 96% of neuropsychiatric drugs fail, including many aimed at autism, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Despite decades of research, traditional animal models and early‑stage drug discovery methods have struggled to translate into effective treatments for complex brain conditions. For families navigating autism and other neurodivergent diagnoses, that failure rate is not abstract. It means years of trial‑and‑error prescribing, side effects, and uncertainty.

Now, a new biotech startup, Organotics, is using patient‑derived brain organoids to fast‑track personalized psychiatry and rethink how psychiatry drugs are developed.

Rethinking Animal Models in Neuropsychiatric Drug Development

“The start with animals,” says Annie Kathuria, a neuroscientist and biomedical engineering professor at Johns Hopkins University. “But a mouse does not get bipolar disorder.”

Animal models have powered extraordinary advances in medicine. But higher‑order human conditions like autism, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and Alzheimer’s disease are shaped by uniquely human neural circuitry, immune signaling, and developmental timing. A mouse can approximate pathways, but it cannot replicate the lived biology of a human brain.

That translational gap contributes to psychiatry’s high drug‑failure rate. Kathuria believes we can do better.

Her startup, Organotics, is raising seed funding to scale a platform designed to rethink how early‑stage neurological and psychiatric drug testing is done.

From Animal Testing to Human Brain Organoids

Organotics uses induced pluripotent stem‑cell technology to take a patient’s blood or skin cell, revert it to a stem cell, and grow miniature brain tissue—organoids—that carry the patient’s DNA.

What distinguishes the platform is complexity. Instead of generating a single cortical region, Kathuria’s team builds interconnected cortical, midbrain, and hindbrain structures, complete with patient‑derived blood vessels. Those vessels help seed immune cells, including microglia, allowing the model to better reflect human brain biology.

“The result is not a full brain. It is a biologically meaningful, scalable model that Kathuria calls ‘human‑adjacent.’”

“We can produce hundreds,” she explains. “Imagine blueberry‑sized mini brains in a dish, all from the same patient.”

That scalability is central to Organotics’ thesis. The company will partner with pharmaceutical and biotech firms to perform early‑stage drug screening directly on patient‑derived brain organoids. Instead of spending five to seven years in animal studies before discovering a drug fails in humans, companies can narrow candidates earlier—on tissue that reflects actual human neurobiology.

Why This Matters For Neurodivergence

Autism was among the earliest areas studied using organoid technology. Kathuria’s academic work focused on severe, genetically defined forms of autism, including high‑penetrance genes such as SHANK3. Rare neurodevelopmental disorders are particularly suited to her precision modeling.

But the implications of Organotics’ model extend beyond rare disease.

Neuropsychiatric conditions are highly heterogeneous. A medication may work for a subset of patients yet fail in a large randomized trial because biological differences were never separated. Organotics’ platform could help identify which mechanisms are active, and which therapies show real signal, before patients themselves become the experiment.

Organotics Plans AI‑Models From Organoid Research

Kathuria envisions pairing organoid data with AI‑driven pattern recognition to classify patients into biologically meaningful subgroups. To do this, Manolis Kellis, MIT professor and head of MIT’s computational biology group, will direct the AI side of Organotics work. The goal is to build an AI model that can eventually identify which drugs will work for an individual patient just via the patient’s history, without needing to grow an organoid at all.

From Academic Innovation To Scalable Platform

Until recently, work with organoids lived within an academic lab. But demand from pharmaceutical and biotech companies is growing across Alzheimer’s disease, autism, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other neurological programs.

Scaling from hundreds to thousands of organoids per month requires standardized production and commercial infrastructure. This is why Organotics was formed as a separate entity.

The Kathuria Lab at Johns Hopkins continues to push the science forward. Organotics focuses on operationalizing the platform for industry collaboration.

Psychiatric drug failure is not only a scientific challenge. It is a capital‑allocation challenge, and a human one. Every late‑stage failure represents billions lost and years delayed for patients who cannot afford to wait.

As a pediatrician, I know how much of neuropsychiatric care still relies on educated guesswork. Technologies like this will not replace clinicians, but they may finally give us tools that match the complexity of the brains we are trying to help.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...