Proximal Sound Prints Elastomer Microstructures Using Ultrasound

•February 20, 2026

0

Why It Matters

PSP enables true 3‑D printing of PDMS microfluidics without chemical reformulation, lowering barriers for rapid prototyping and small‑scale production in biotech and lab‑on‑a‑chip markets.

Key Takeaways

- •PSP reaches 0.2 mm feature size in PDMS

- •Power consumption drops to ~5 W, four‑fold lower

- •Deposition rate climbs to 250,000 mm³/h

- •Works with native PDMS ratios, preserving optical clarity

- •Multi‑material printing demonstrated, including pigment colloids

Pulse Analysis

The microfluidics community has long relied on soft‑lithography to shape polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), a material prized for its biocompatibility and optical transparency. Conventional 3‑D printing methods either require photopolymers that alter PDMS chemistry or demand complex rheological tuning, limiting adoption for researchers who need the native elastomer. Proximal Sound Printing sidesteps these constraints by focusing cavitation at a thin aluminum barrier, creating a sonochemically ultra‑active reactor (SUAR) that polymerizes PDMS precisely where the print head moves. This acoustic confinement delivers micron‑scale control previously unattainable with sound‑based curing.

Beyond resolution, PSP’s energy profile marks a significant step forward. Earlier Direct Sound Printing consumed around 20 W of electrical power, much of which never reached the resin. By routing ultrasound through an acoustic chamber and depositing only about 0.32 W of acoustic power at the barrier, PSP operates on roughly 5 W total—equivalent to a low‑power desktop printer. Simultaneously, the volumetric deposition rate jumps to 250,000 mm³ per hour, rivaling fused filament fabrication and direct ink writing for bulk builds. These metrics position PSP as a competitive alternative for both high‑resolution prototyping and larger‑scale elastomeric part production.

Commercially, the ability to print functional PDMS structures without reformulating the polymer could accelerate time‑to‑market for diagnostic chips, organ‑on‑a‑chip platforms, and soft robotics components. However, practical deployment hinges on stabilizing the aluminum barrier, automating resin delivery to avoid bubble formation, and establishing robust metrology for feature consistency. If these engineering hurdles are resolved, PSP may become the go‑to desktop solution for labs seeking rapid, low‑cost fabrication of true PDMS microdevices, reshaping the supply chain for biomedical research and low‑volume manufacturing.

Proximal Sound Prints Elastomer Microstructures Using Ultrasound

Proximal Sound Printing (PSP)

Proximal Sound Printing (PSP) is a new sound‑driven additive manufacturing process that claims it can directly 3D print fine PDMS microstructures with far better resolution and repeatability than earlier “sound printing” attempts.

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is the go‑to elastomer in microfluidics and soft‑lithography applications because it is biocompatible, optically clear, and easy to handle in labs. The problem is that PDMS is a heat‑curing thermoset, and most 3D‑printing processes require either photopolymers (SLA and DLP) or carefully tuned rheology (direct ink writing). Those routes typically push you into custom resin chemistry, incompatible initiators, or support baths, and the “native” PDMS formulation that researchers really want often gets compromised.

A team led by Muthukumaran Packirisamy at Concordia University (with collaborators at UC Davis) has been working on ultrasound‑driven curing for a while under the banner of Direct Sound Printing (DSP).

In their earlier concept, focused ultrasound creates cavitation bubbles, and the bubble collapse triggers sonochemical reactions that drive polymerization in heat‑curing resins.

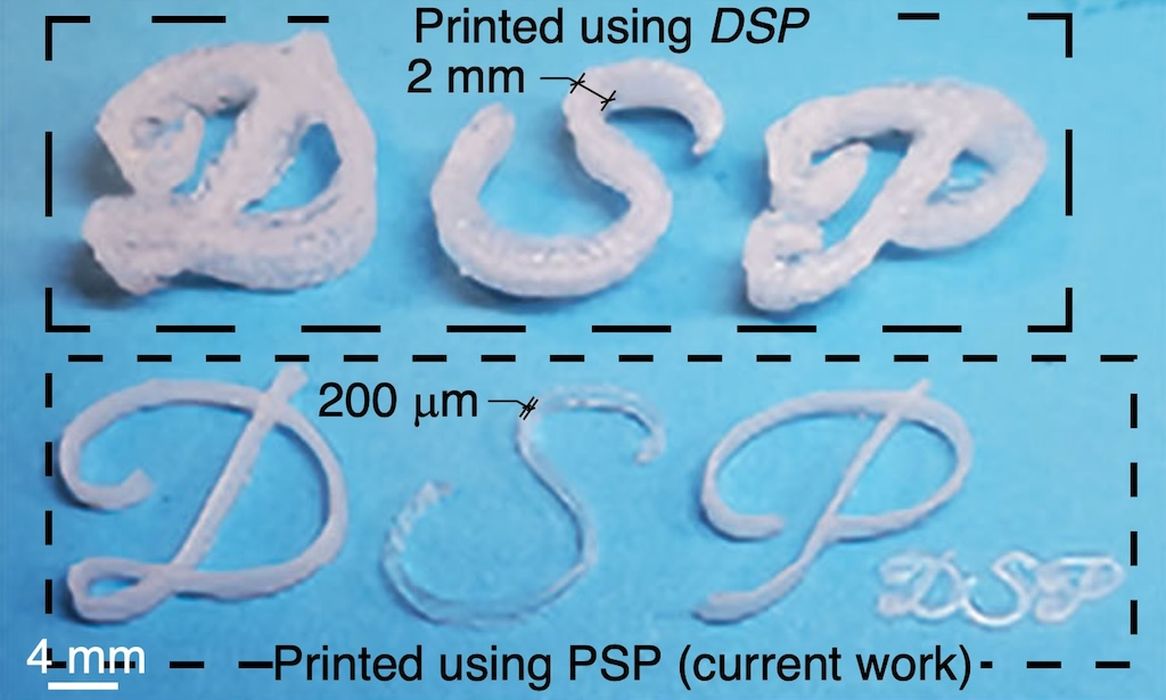

The new paper argues that DSP’s practical limits were the ones you might expect: feature sizes in the one‑to‑two‑millimeter range, fluid motion that disturbs the build zone, and difficulty producing more complex or multi‑material structures.

Proximal Sound Printing

PSP keeps the same basic physics, but the geometry changes in a way that is important.

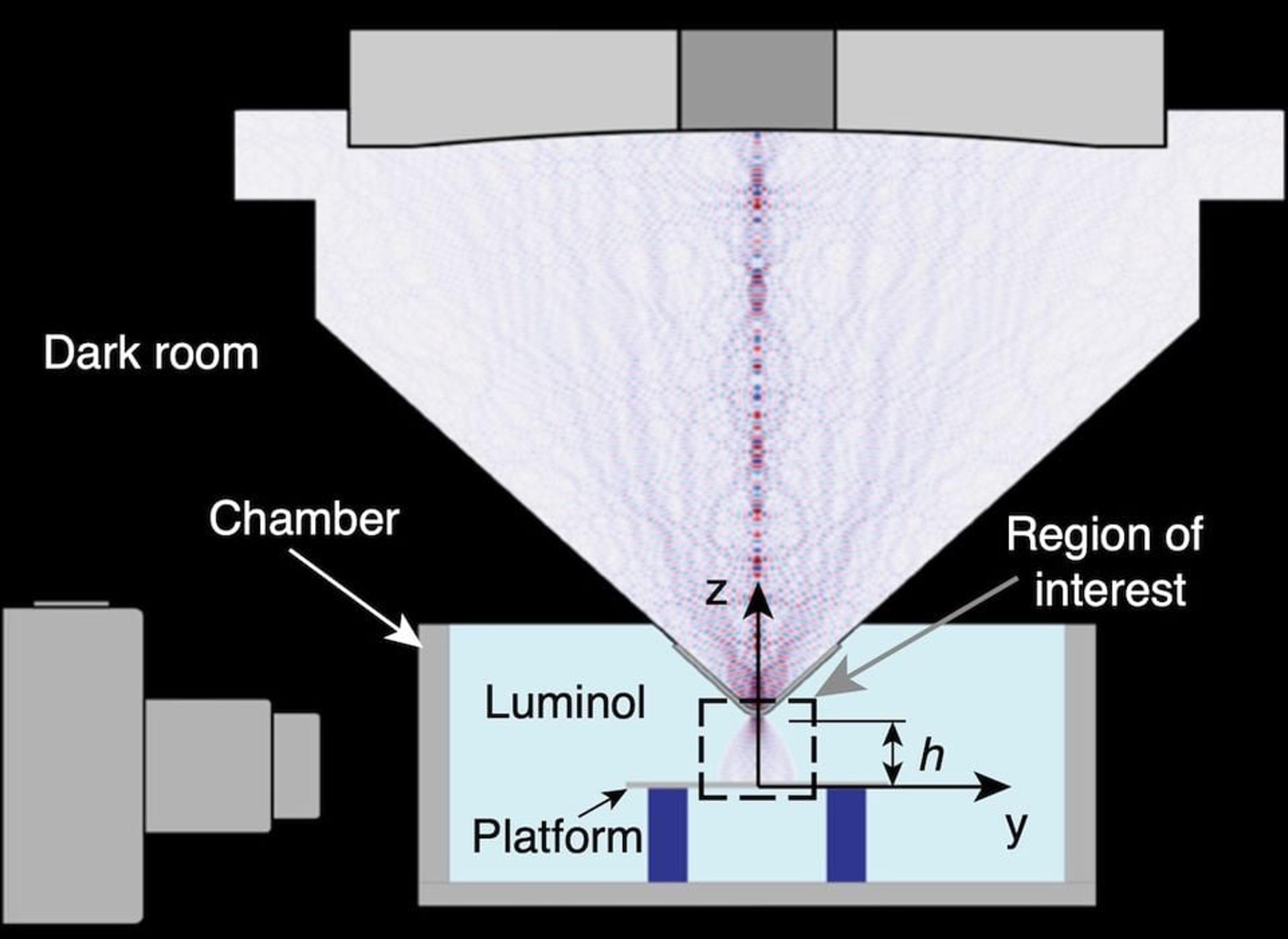

Instead of trying to cure “in the open,” PSP routes ultrasound through a guiding acoustic chamber that ends in a small printing aperture covered by a thin aluminum‑film barrier.

The printing resin sits immediately outside that barrier, and cavitation occurs right at the barrier surface inside the resin, forming a highly localized reactive zone that the authors call a sonochemically ultra‑active reactor (SUAR). The substrate (or the print head) then moves to “draw” the part pixel by pixel in the usual manner.

The main claim of the work is a practical feature size of 0.2 mm in PDMS, demonstrated by printing the letters “DSP” where PSP produces roughly 0.2 mm line thickness versus about 2 mm for DSP in the same material. PSP wins the resolution battle.

They also printed microfluidic structures, including a Y‑channel with 0.3 mm inlet channels and a 0.5 mm main channel, plus a serpentine micromixer with 0.5 mm channels, and showed laminar flow versus mixing behavior using dyed streams. In other words, their 3D‑printed parts functioned as designed.

On the energy side, PSP is a low‑power solution because much of the electrical input never makes it past the barrier. Under one test their modeling estimates a maximum deposited acoustic power of about 0.32 W at the barrier surface. They also point out that their earlier DSP demonstrations used about 20 W electrical input, so PSP reduces applied electrical power to only 5 W in that setup—a four‑times reduction.

There is also throughput to consider: with a larger aperture, they report a volumetric deposition rate around 250,000 mm³ /hour, compared with about 15,000 mm³ /hour for DSP, and they argue it is in the same range as other 3D‑print processes such as FFF and direct ink writing for bulk deposition. That rate, however, comes with much thicker features; the process trades resolution for deposition by swapping aperture sizes and layer thickness.

PSP is not a drop‑in replacement for conventional microfabrication quite yet. The setup uses a focused ultrasound transducer, a water‑filled acoustic chamber, an aluminum barrier film, and a tight gap control between the tip and substrate; any drift in that gap likely changes the SUAR geometry and therefore feature size.

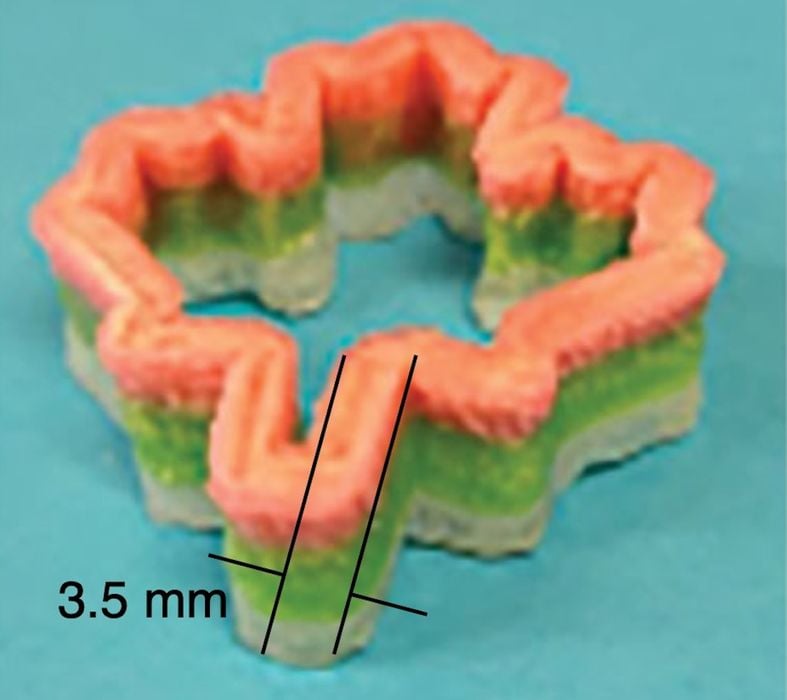

The paper also shows that PDMS mixing ratio affects internal porosity and optical clarity (for example, a 10:1 ratio tends to be more porous, while 16:1 trends more transparent), which is useful, but it also means process recipes will be application‑specific.

The authors demonstrate multi‑material printing and even PDMS colloids (a glow‑pigment suspension), which is intriguing for functional microdevices. The big open questions for production are long‑run stability of the barrier, automation of resin delivery without bubbles, metrology for feature control, and whether the approach can be packaged into a robust toolchain for labs that do not want to babysit acoustic alignment.

If PSP holds up outside a controlled research environment, it could become one of the rare techniques that prints “real” PDMS microfluidics without reformulating the chemistry, and that is a very tempting promise for the future.

Source: Nature

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...