Reed Critical Frequency in Vertical Motors: Improving Resonance Prediction

•February 11, 2026

0

Why It Matters

Accurate RCF prediction prevents costly downtime and extends motor‑pump life, a critical advantage as VFDs push equipment through resonance zones. Faster, reliable modeling enables engineers to design bases and supports that mitigate vibration before installation.

Key Takeaways

- •RCF is vertical motor's first bending natural frequency

- •Resonance occurs when excitation matches RCF, causing high vibrations

- •Traditional FEA and bump tests are costly and slow

- •Two-degree-of-freedom model yields ±5‑10% accuracy, cuts time 40‑50%

- •VFDs broaden speed range, raising resonance risk without accurate prediction

Pulse Analysis

Uncontrolled vibration remains a leading cause of premature failure in rotating equipment, and vertical motors are especially vulnerable. Their upright shaft and rotor act like a cantilevered reed, so the first natural bending frequency—known as reed critical frequency (RCF)—dominates the dynamic response. If the motor’s operating speed, power‑line frequency, or VFD‑induced sweep aligns with RCF, resonance amplifies forces, leading to rapid bearing wear, shaft deflection, and even catastrophic breakdowns. Understanding RCF therefore underpins reliable motor‑pump system design.

Historically engineers relied on finite‑element analysis, bump testing, or simplified NEMA formulas to estimate RCF. While FEA offers detail, it demands extensive modeling time and computational resources; bump tests require a fully assembled unit, delaying feedback until late in the design cycle; and simplified equations ignore bearing stiffness and overhung loads, producing errors of 20 % or more. Wolong Electric America’s two‑degree‑of‑freedom (2‑DOF) approach treats the motor as a flexible beam coupled to rotating masses, incorporating bearing stiffness and enclosure mass distribution. The result is a spreadsheet‑based digital twin that predicts RCF within ±5‑10 % and cuts analysis time by nearly half.

The proliferation of variable‑frequency drives intensifies the need for precise RCF data because VFDs sweep motors through a wide speed spectrum, often crossing resonance zones that fixed‑speed units avoid. With accurate, fast modeling, designers can size bases, select bearing stiffness, and position overhung loads to keep operating points safely away from the critical frequency before hardware is built. This proactive strategy reduces unplanned shutdowns, lowers maintenance budgets, and extends equipment lifespan—benefits that resonate across pump manufacturers, plant operators, and OEMs seeking competitive advantage in a market increasingly driven by reliability and efficiency.

Reed Critical Frequency in Vertical Motors: Improving Resonance Prediction

Understanding Reed Critical Frequency (RCF) in Vertical Motors

Uncontrolled vibration remains one of the most common causes of failure in rotating equipment, driving premature bearing wear, unplanned outages, and safety risks. In vertical motor applications, a key factor behind these vibration problems is reed critical frequency (RCF)—the motor's first natural bending frequency. When operating conditions align with this frequency, resonance can occur, amplifying vibration levels and accelerating mechanical damage. Understanding how RCF works and how to predict it accurately is essential for designing vertical motor systems that operate reliably over time.

By better understanding RCF, why vertical motors are especially prone to resonance risks, and how engineers can accurately predict and avoid these conditions, equipment manufacturers and end users alike can significantly extend machine life and reduce maintenance costs.

What Is Reed Critical Frequency in Vertical Motors?

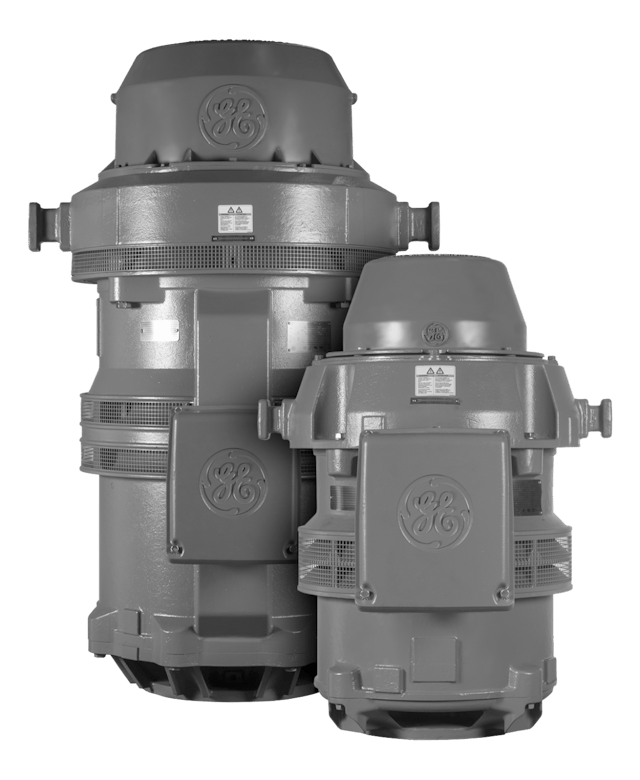

Reed critical frequency is the first natural bending frequency of a vertical motor system. To visualize this, consider how a tuning fork vibrates when struck; the fork oscillates at a specific frequency, amplifying the input energy. Vertical motors behave in a similar way. Because their shaft and rotor assembly are upright, they act like a cantilevered reed: flexible, unsupported at one end, and prone to bending motion under excitation.

A vertical motor's reed‑like structure makes it more prone to bending vibrations than horizontal designs.

RCF depends on factors including shaft length and stiffness, rotor mass and distribution, and bearing support stiffness. When the natural frequency coincides with an excitation frequency, such as the 50 Hz or 60 Hz power supply, the motor enters resonance. Even small inputs of energy can create disproportionately large vibrations. Resonance accelerates wear on bearings, thrust assemblies, and foundations, and in the worst cases, it can cause catastrophic component failure.

Why Vertical Motors Are More Susceptible to Resonance

Unlike horizontal motors, vertical motors rest on a single base. The design makes them more flexible, especially with added overhung loads from couplings, impellers, and pumps. This reed‑like structure makes them uniquely susceptible to resonance.

Symptoms of Resonance in Vertical Motor Systems

Operators can sometimes detect when a motor is approaching resonance. Vibration monitoring shows sudden spikes in radial vibration, with amplitudes peaking near the critical frequency. Motors may produce a low‑frequency hum, buzzing, or rattling. High displacement at the top cover, cycling vibrations near RCF, and visible shaft wobble are further signs. Premature bearing deterioration is also common, often accompanied by overheating, thrust bearing wear, and coupling misalignment. Over time, the foundation itself may loosen, compounding the problem and creating long‑term risks.

-

Short‑term effects: alarms or nuisance shutdowns.

-

Long‑term effects: bent shafts, degraded thrust bearings, costly motor replacement, and downstream pump downtime.

Determining RCF: Traditional Calculation Methods

The pump industry requires accurate RCF values early in the design process, as pump manufacturers must model the combined dynamics of the pump, motor, and foundation. Traditionally, engineers have turned to finite element analysis (FEA), bump tests, and simplified formulas.

Limitations of FEA, Bump Tests, and Simplified RCF Formulas

-

FEA – Accurate but time‑intensive and resource‑heavy; impractical for many design variations.

-

Bump tests – Require a fully assembled motor, delaying results until late in the design cycle.

-

Simplified formulas (e.g., NEMA MG‑1) – Quick but oversimplify system dynamics, assume rigid foundations, and ignore load effects; errors can exceed ±20 %.

These drawbacks—cost, speed, and accuracy—leave manufacturers dissatisfied. Inaccurate predictions prevent proper base design, and errors are amplified when plants retrofit VFDs or modify equipment without re‑evaluating RCF. The industry now demands more reliable predictive data.

Improving RCF Prediction with Two‑Degree‑of‑Freedom Modeling

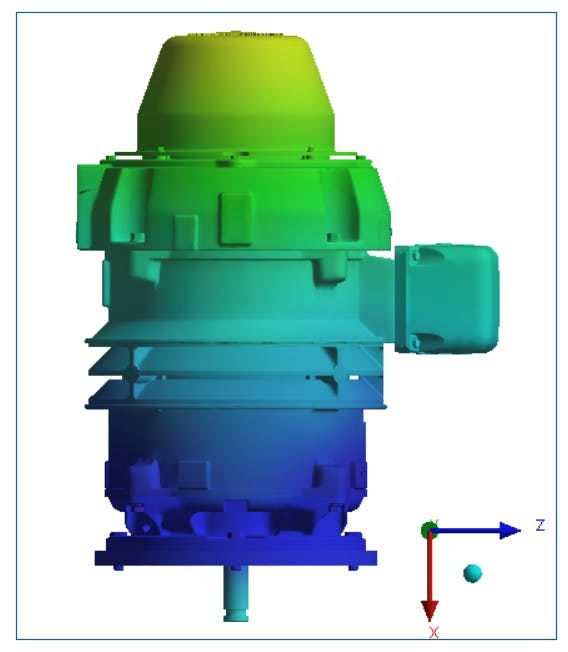

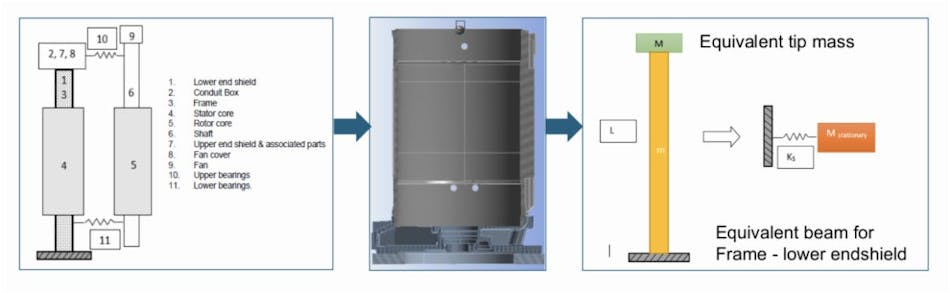

Recognizing these limitations, Wolong Electric America engineers developed a mathematical model based on a two‑degree‑of‑freedom system. This approach accounts for contributions of both stationary and rotating parts, as well as bearing stiffness, providing a more complete representation of vertical motor dynamics.

Key features of the model:

-

Flexible beam representation of the frame and lower end shield supporting stationary components.

-

Rotating parts connected through bearing stiffness.

-

Equivalent mass calculations using enclosure‑specific power factors derived from the Timoshenko beam model, allowing variations in enclosure type, frame or P‑base size, and attached part location/orientation.

Results:

-

Predictive accuracy improved to ±10 %, and in some cases as close as ±5 %.

-

Calculation time reduced by 40–50 % compared with traditional methods.

-

Engineers can input design parameters into a spreadsheet tool and receive RCF, static deflection, and center‑of‑gravity values needed for pump‑base design.

The model functions as a digital twin or “virtual motor,” enabling rapid simulation of configuration changes, mass adjustments, support‑structure modifications, or mounting variations to assess resonance impact before hardware is built or installed.

How Variable Frequency Drives Increase Resonance Risk

For many years, manufacturers relied on generalized values across product lines, often resulting in errors of 40–50 % between predicted and actual resonance points. Fixed‑speed motors allowed operators to avoid resonance zones by staying within stable ranges.

With the introduction of variable frequency drives (VFDs), motors now operate across broad speed ranges, often passing directly through resonance frequencies. This shift has heightened the demand for accurate predictive tools and moved the industry toward proactive design‑stage analysis rather than reactive maintenance.

Advances in computing power and modeling have made this shift possible. Digital models act as accurate surrogates for physical motors, allowing engineers to anticipate resonance issues early and refine designs with confidence.

Designing Vertical Motor Systems to Avoid Resonance

Traditional approaches forced manufacturers to choose between precision, speed, and cost. Wolong’s two‑degree‑of‑freedom model demonstrates that these trade‑offs are no longer necessary. By providing a fast, accurate, and easy‑to‑apply method across product lines, engineers can anticipate and mitigate resonance risks during the design stage rather than responding to field failures.

Takeaways

-

Understand that RCF is the first natural bending frequency of a vertical motor and a primary driver of resonance.

-

Recognize the unique susceptibility of vertical motors due to their cantilevered, reed‑like structure.

-

Use advanced two‑degree‑of‑freedom modeling to achieve ±5–10 % prediction accuracy with significantly reduced analysis time.

-

Incorporate VFD operating ranges into the design process to avoid crossing resonance frequencies.

-

Leverage digital twin tools to iterate designs quickly, ensuring reliable, long‑lasting motor‑pump systems.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...