Understanding the Physics at the Anode of Sodium-Ion Batteries

•February 20, 2026

0

Why It Matters

Understanding and engineering hard‑carbon pore structures can close the energy‑density gap between sodium‑ion and lithium‑ion batteries, accelerating NIB adoption for grid‑scale storage. Faster ion transport and higher capacity directly support renewable‑energy integration and carbon‑neutral goals.

Key Takeaways

- •Hard carbon pores ~1.5 nm optimal for Na storage.

- •Na ions form 3D quasi‑metallic clusters early.

- •Defect‑adsorbed Na reduces Na‑C interaction, aids clustering.

- •Branching pores create bottlenecks, slowing diffusion.

- •Design guidelines target larger, connected nanopores.

Pulse Analysis

Sodium‑ion batteries (NIBs) are emerging as a cost‑effective, sustainable alternative to lithium‑ion systems because sodium is abundant and inexpensive. Yet, their commercial viability hinges on matching the energy density of LIBs, which is largely dictated by the anode material. Hard carbon, with its porous, amorphous structure, has become the default anode, but its nanoscopic ion‑storage mechanisms remained opaque, limiting rational design. Recent advances in computational power now allow researchers to probe these mechanisms at the atomic level, offering a pathway to bridge the performance gap.

In the latest study, Professor Yoshitaka Tateyama’s team employed high‑accuracy density functional theory‑based molecular dynamics on the Fugaku supercomputer to model hard‑carbon nanopores. The simulations showed that sodium ions abandon a two‑dimensional adsorption state almost immediately, forming three‑dimensional quasi‑metallic clusters once the pore diameter reaches roughly 1.5 nm—exactly the size reported in experimental work. Interestingly, sodium ions bound to defects do not act as nucleation sites; instead, they weaken Na‑C bonds and free space, encouraging larger cluster growth. These atomistic insights clarify why certain pore geometries deliver higher reversible capacity.

The practical upshot is a clear set of design guidelines: engineer hard‑carbon anodes with uniformly sized pores around 1.5 nm and minimize abrupt branching that creates diffusion bottlenecks. By doing so, manufacturers can boost both the specific capacity and the rate capability of NIBs, making them more attractive for grid‑scale storage and electric‑vehicle applications. As renewable energy penetration rises, faster‑charging, high‑energy‑density sodium‑ion batteries could become a cornerstone of the carbon‑neutral transition, prompting further investment in material‑scale modeling and scalable synthesis techniques.

Understanding the physics at the anode of sodium-ion batteries

Feb 20, 2026

(Nanowerk News) Sodium‑ion batteries (NIBs) are gaining traction as a next‑generation technology to complement the widely used lithium‑ion batteries (LIBs). NIBs offer clear advantages versus LIBs in terms of sustainability and cost, as they rely on sodium—an element that, unlike lithium, is abundant almost everywhere on Earth. However, for NIBs to achieve widespread adoption, they must reach energy densities comparable to LIBs.

State‑of‑the‑art NIB designs use hard carbon (HC), a porous and amorphous type of carbon, as an anode material. Scientists believe that sodium ions aggregate into tiny quasi‑metallic clusters within HC nano‑pores, and this “pore filling” process remains the main mechanism contributing to the extended reversible capacity of HC anodes. Despite some computational studies on this topic, the fundamental processes governing sodium storage and transport in HC remain unclear. Specifically, researchers have struggled to explain how sodium ions can gather to form clusters inside HC pores at operational temperatures, and why the overall movement of sodium ions through the material is sluggish.

Against this backdrop, a group led by Professor Yoshitaka Tateyama from the Laboratory for Chemistry and Life Science, Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo), Japan, set out to model this complex nanoscopic behavior to address these long‑standing questions. In their latest study, published in Advanced Energy Materials (“Unveiling Dominant Processes of Na Cluster Formation and Na‑Ion Diffusion in Hard Carbon Nano‑Pore: A DFT‑MD Study”, https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1002/aenm.202505227), the team ran high‑accuracy density functional theory‑based molecular dynamics (DFT‑MD) simulations on powerful supercomputers, including Fugaku, to create localized models of the HC structure.

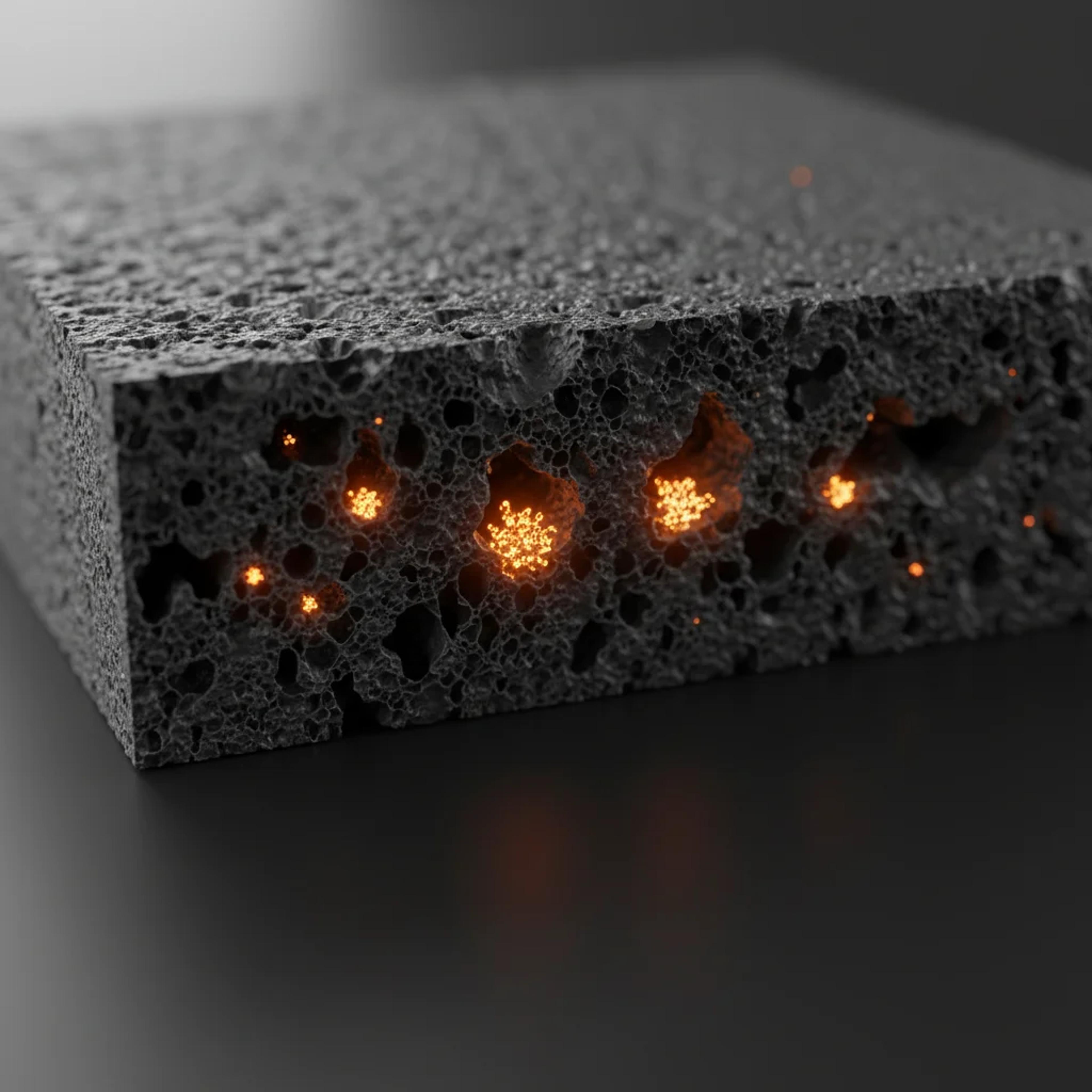

Image: Understanding the behavior of sodium ions in the anode of Na‑ion batteries – Supercomputer‑based simulations reveal the intricacies of sodium‑ion clustering and transport in hard carbon nano‑pores. The results show that a bottleneck effect can lead to the sluggish diffusion of ions in sodium‑ion batteries, while also providing useful nanostructural design guidelines to increase the energy density of hard carbon anode. (Image credit: Institute of Science Tokyo)

The simulations explored different arrangements of sodium ions and graphene sheets as self‑contained representations of the nanopores and graphitic regions in HC. The results provided unprecedented clarity on the mechanisms controlling both capacity and reaction kinetics at the anode in NIBs. First, the simulations revealed that sodium ions in nanopores transition early from a two‑dimensional adsorption state to a three‑dimensional, quasi‑metallic cluster state.

Based on this finding, the team theoretically determined the optimal nanopore diameter for stable sodium storage—approximately 1.5 nm—which matches experimental results. They also found that certain defect‑adsorbed sodium ions, rather than acting as nucleation sites, actually promote sodium cluster formation by reducing Na‑C interaction and the available space for incoming sodium ions in HC nano‑pores.

Moreover, the DFT‑MD simulations showed that while sodium ions exhibit locally fast diffusion in well‑connected areas of HC, branching or reconnection regions act as severe bottlenecks to ion migration. These narrower transition regions become clogged by sodium ions until enough repulsive force builds up to remove the blockage, creating a rate‑limiting step that explains the material’s sluggish performance.

“By integrating these new insights, our study provides clearer design guidelines for HC materials capable of storing sodium efficiently, thereby contributing to the development of better NIBs,” remarks Tateyama.

High‑energy‑density batteries are essential for storing electricity generated by solar and wind farms. In this sense, NIBs could be a key enabler in the current shift toward renewable energy generation systems.

“Ultimately, the widespread adoption of NIBs will increase the overall supply of batteries in society, supporting the realization of a carbon‑neutral future,” concludes Tateyama.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...