China’s Carbon Market Expands Into Heavy Industry As USA Regresses

•February 16, 2026

0

Why It Matters

Expanding reporting creates the data infrastructure needed for broader carbon pricing, influencing industrial investment and trade competitiveness. The divergent policy paths of China, the EU and the U.S. reshape global climate‑risk landscapes and carbon‑border dynamics.

Key Takeaways

- •China adds six heavy‑industry sectors to carbon reporting

- •Reporting precedes pricing to build credible MRV infrastructure

- •Coverage could reach 70‑80% of emissions by 2030

- •EU ETS prices far exceed China’s modest current levels

- •U.S. federal climate rule rollback contrasts global tightening

Pulse Analysis

China’s latest regulatory move signals a strategic shift from pilot projects to a comprehensive, data‑driven carbon market. By mandating emissions reporting for petrochemicals, chemicals, flat glass, copper smelting, papermaking and civil aviation, the government is creating the measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) backbone essential for future allowance allocation. This incremental approach mirrors the early phases of the EU’s ETS, where robust reporting preceded the transition from free allocation to auctioning, ensuring market credibility while protecting industrial competitiveness.

The expansion has profound implications for both domestic industry and international trade. As China moves toward integrating these sectors into its ETS by the late 2020s, the carbon price—currently 40‑90 yuan per ton—could rise as free allowances shrink and auction shares increase. Higher internal prices would help Chinese exporters meet the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), reducing the risk of tariff penalties and strengthening China’s position in global supply chains. Simultaneously, the broader coverage amplifies the signal to investors, nudging capital toward low‑carbon technologies such as renewable power, electric arc furnaces, and hydrogen‑based processes.

In stark contrast, the United States has dismantled the legal foundation for federal climate regulation by revoking the 2009 endangerment finding, effectively pausing nationwide CO₂ standards. While Europe tightens its cap and expands coverage, China’s methodical scaling of its ETS underscores a divergent global trajectory: state‑led market building versus regulatory retreat. For businesses operating across these regions, understanding the pace of China’s market maturation and the EU’s price trajectory is crucial for risk management, compliance planning, and strategic investment decisions.

China’s Carbon Market Expands Into Heavy Industry As USA Regresses

China’s national carbon market has reached another expansion point, and the signal is larger than it first appears.

The Ministry of Ecology and Environment has extended mandatory carbon reporting beyond the original heavy sectors to include petrochemicals, chemicals, flat glass, copper smelting, papermaking, and civil aviation. That move does not immediately impose a carbon price on those industries, but it builds the administrative architecture required to do so. China’s approach to climate policy has been iterative and staged. The reporting expansion is the next logical step in a system that is moving from pilot status to a macro‑economic instrument.

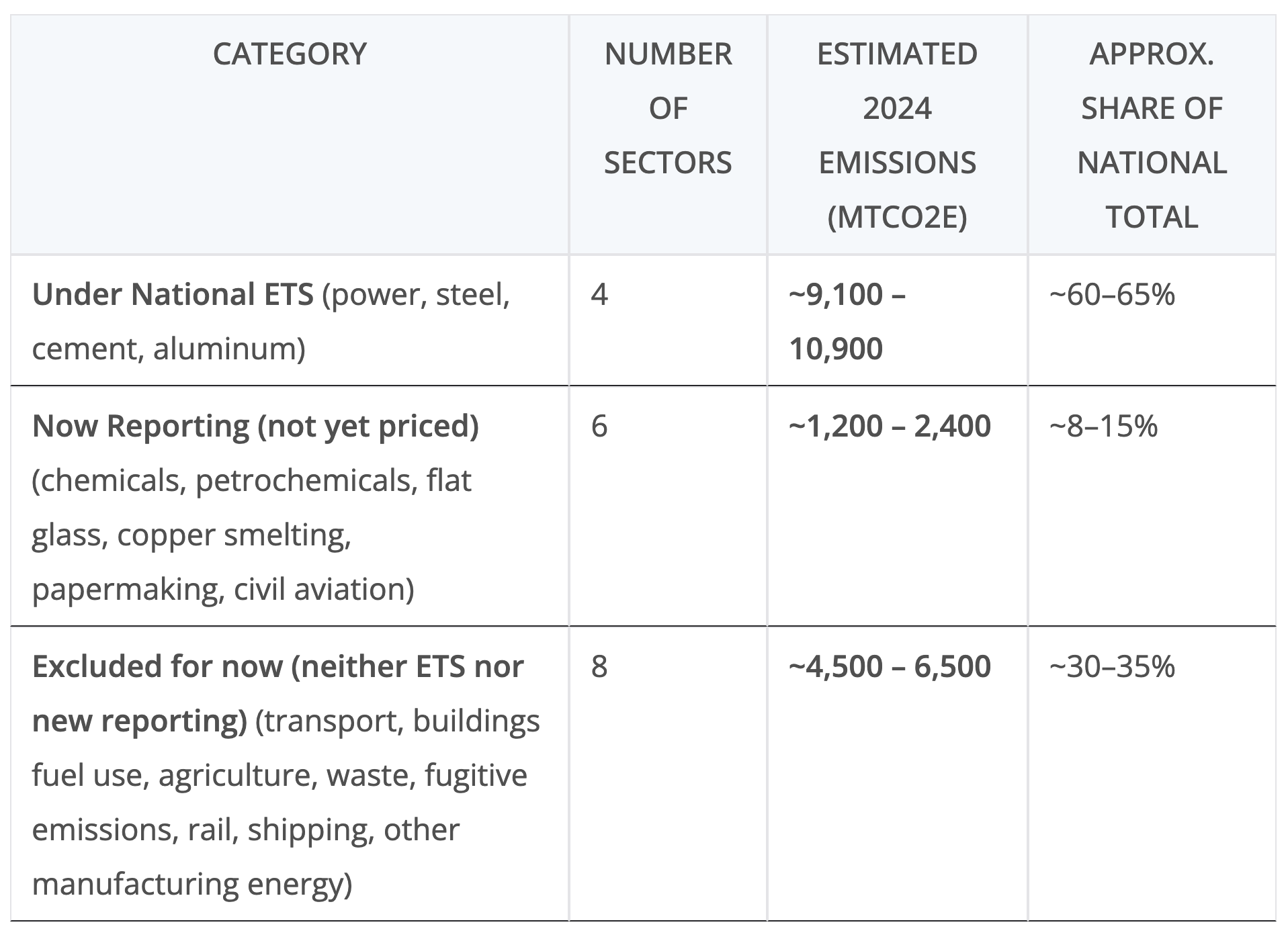

The national emissions trading system today directly prices four sectors. Power generation, steel, cement, and aluminum are under compliance obligations. Together they account for roughly 9,000 to 11,000 million tons of CO₂ per year, out of a national total in the range of 15,000 to 16,000 million tons of CO₂‑equivalent. Power generation alone contributes around 6,000 to 7,000 million tons annually, which makes it the anchor of the system. Steel adds roughly 1,800 to 2,200 million tons. Cement contributes about 1,000 to 1,200 million tons, largely from calcination chemistry. Aluminum adds another 300 to 500 million tons depending on the coal intensity of electricity inputs. In other words, China’s ETS already covers about 60 % to 65 % of national emissions by volume, making it the largest carbon market in the world in terms of covered emissions.

As I’ve published on over time, each of these ETS‑included sectors is undergoing rapid transformation with national industrial and energy policies separate from the generic carbon price. China is building as much renewable generation as the rest of the world combined each year, often more in a year than major countries have in total. China has stopped approving new coal‑fired blast furnaces for steel and is pivoting to scrap‑fed electric arc furnaces. Its infrastructure boom is fading rapidly as it’s built the majority of what it needs, just as Europe and North America did in the second half of the 20th Century, so cement is in decline. It’s shifted coal‑heavy aluminum processing in the northwest to hydroelectric‑heavy in the southeast and scrap aluminum instead of primary aluminum, as well as increasingly powering northwest aluminum with renewables.

The design of the ETS system matters as much as the coverage. China began with intensity‑based allocation, where firms receive free allowances linked to output benchmarks, just as the EU provided allowances for key sectors like maritime shipping and aviation that it has eliminated in recent years. That means emissions can grow if production grows, as long as emissions per unit stay within benchmark ranges. Prices have therefore remained modest. The carbon price has generally traded between 40 and 90 yuan per ton, equivalent to roughly $8 to $13 per ton. Recent averages have clustered near 60 to 70 yuan, or around $9 to $10 per ton. At that level, the price is more signal than driver. It influences dispatch margins and corporate planning, but it does not force rapid fuel switching or industrial transformation on its own. By contrast, the EU’s ETS has hovered between €70 and €100 ($84 to $120) per ton over the past few years and has a target in the €300 range per budgetary guidance.

The newly required reporting sectors represent the next industrial layer. Petrochemicals and chemicals together likely account for 1,000 to 2,000 million tons of CO₂ annually depending on classification boundaries. Flat glass adds perhaps 50 to 120 million tons. Copper smelting contributes 20 to 70 million tons. Papermaking is in the 70 to 150 million‑ton range. Civil aviation in China emits roughly 80 to 140 million tons depending on traffic levels. Combined, these sectors represent another 1,200 to 2,400 million tons of emissions. That is not marginal—it is around 8 % to 15 % of the national total.

Reporting precedes pricing because carbon markets depend on measurement. Monitoring, reporting, and verification infrastructure has to be credible before allowance allocation can be defensible. Benchmarks have to be built from real production and emissions data. Compliance systems need auditing capacity. This is exactly the same as the EU CBAM reporting requirement introduced a couple of years ago with first actual fiscal collection starting this year. China has taken this approach consistently. The power sector spent years under pilot and reporting conditions before the national ETS became operational. Steel and cement followed the same pattern. Extending reporting requirements in 2025 and 2026 suggests that inclusion into compliance cycles could occur around 2027 or 2028. That timing aligns with policy signals indicating that major industrial sectors are expected to be incorporated before 2030.

Several large emissions pools remain outside both the ETS and the new reporting scope. Road transport likely emits between 800 and 1,200 million tons annually. Buildings combustion—burning fuels inside buildings to provide hot water, cooking and comfort heat—contributes around 700 to 1,100 million tons. Agriculture, dominated by methane and nitrous oxide, is in the 800 to 1,000 million‑ton range. Fugitive emissions from coal mining and oil and gas supply chains add another 700 to 1,200 million tons. Waste and wastewater add perhaps 200 to 350 million tons. Shipping and rail are smaller but still material. These sectors are structurally more complex. They involve diffuse actors, smaller facilities, and more variable measurement regimes. Integrating them into a carbon market requires different regulatory tools and likely a longer timeline.

However, road‑transport emissions are likely to start collapsing due to other national policies and efforts. Electric cars, trucks and buses dominate sales in the country now, and are ramping up rapidly. Similarly, buildings combustion is pivoting rapidly to heat pumps, district heating and general electrification.

Looking forward, a plausible sequence would see the current reporting sectors enter the ETS between 2027 and 2030. That would bring coverage to perhaps 70 % to 80 % of national emissions. A broader move toward economy‑wide inclusion is unlikely before the mid‑2030s. Transport and buildings could be phased in using fuel‑supplier obligations or upstream pricing mechanisms. Full sectoral inclusion aligned with a 2060 neutrality pathway likely occurs between 2035 and 2045. The system will probably expand in scope before it tightens sharply in constraint.

Carbon‑price trajectories will depend on that tightening. Under a slow‑reform path with heavy free allocation and gradual benchmark adjustments, prices might rise from roughly $20 per ton by 2030 to $60–$80 per ton by 2050 in real terms. Under a structured transition, which appears more consistent with current policy direction, prices could reach $25–$30 per ton by 2030, $70–$100 per ton by 2040, and $125–$165 per ton by 2050. Under an aggressive convergence model similar to the European Union, prices could exceed $200 per ton by mid‑century. The key variable is whether China shifts from intensity‑based allocation to a declining absolute cap and increases the share of auctioned allowances.

Adding sectors by itself does not automatically raise prices. When new industries enter, they typically receive free allowances linked to output benchmarks. That can expand both demand and supply in parallel. Price pressure emerges when allowance scarcity increases. Scarcity increases when caps tighten relative to production, when benchmarks are ratcheted down, and when free allocation declines. Auctioning plays a critical role. If 20 % to 40 % of allowances were auctioned instead of allocated freely, compliance costs would become more visible and price discovery more robust.

China has several mechanisms available to raise the effective carbon price over time. It can lower benchmark intensities year by year. It can introduce partial auctioning. It can tighten verification standards to reduce overallocation. It can limit the use of offsets under the revived China Certified Emission Reduction (CCER) program, a voluntary carbon‑offset market. It can move toward an absolute cap during the 2030–2035 window. Each of these shifts incrementally increases scarcity and strengthens the investment signal.

The international dimension adds strategic logic. The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) places a carbon cost on imported steel, cement, aluminum, and other goods based on embedded emissions. Europe remains one of the largest trading blocs in the world. If Chinese producers face a $80–$100 per ton carbon cost at the EU border, paying $80–$100 domestically under a national ETS keeps that value inside China’s fiscal system. A stronger domestic carbon market reduces exposure to external carbon tariffs. It also supports claims of regulatory equivalence in trade negotiations.

The European Union’s ETS, the basis of the CBAM, has evolved over roughly 25 years from an overallocated pilot with prices that collapsed below $10 per ton into a mature cap‑and‑trade system covering power, heavy industry, and aviation with prices that have recently ranged between $70 and $100 per ton. It moved in phases from free allocation toward significant auctioning, tightened its cap through linear reduction factors, and created mechanisms such as the Market Stability Reserve to absorb surplus allowances and manage volatility. Coverage expanded gradually while scarcity was engineered more deliberately over time.

China’s ETS, by contrast, launched nationally much later and began with intensity‑based allocation and heavy free distribution in order to stabilize industrial competitiveness and administrative capacity. Instead of tightening scarcity first and expanding later, China is expanding coverage while building measurement infrastructure, with the shift toward absolute caps and higher auction shares still ahead. The EU model reflects a market that learned to correct early design flaws through price reinforcement and structural reform, while China’s progression reflects a state‑directed sequencing approach that prioritizes scale and data integrity before pushing price levels into transformative territory.

While China is expanding reporting obligations in 2025 and preparing additional industrial sectors for inclusion in its national carbon market, the United States has moved in the opposite direction at the federal level. In early 2026, the Environmental Protection Agency finalized a rule revoking the 2009 greenhouse‑gas endangerment finding, the legal determination that carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare under the Clean Air Act. That finding, rooted in the Supreme Court’s Massachusetts v. EPA decision, formed the statutory foundation for federal regulation of vehicle emissions, power‑plant standards, and broader climate controls for more than fifteen years. Removing it does not simply relax a rule; it dismantles the legal trigger that made federal greenhouse‑gas regulation mandatory once the science was established.

The timing is striking. As China widens carbon reporting to petrochemicals, chemicals, aviation, and other heavy sectors and signals likely inclusion into compliance cycles before 2030, and as the European Union continues tightening its cap, expanding coverage, and implementing its border carbon mechanism, the United States has withdrawn from the legal architecture that anchored its federal climate action. China is building measurement capacity in 2025 and 2026 to support future tightening. The EU is reinforcing scarcity through cap reductions and market‑stability mechanisms. Washington, by contrast, has stepped away from the statutory basis for regulating CO₂ at all. The divergence is not abstract; it reflects institutional direction. In Beijing and Brussels, carbon pricing and regulatory frameworks are being consolidated and extended. In Washington, the federal climate framework has been rolled back at the moment when other major economies are embedding theirs more deeply into industrial policy and trade strategy.

Viewed in aggregate, the reporting expansion and probable sector‑inclusion schedule represent institutional maturation. China’s climate policy is moving from pilot experimentation to structured integration into industrial planning. Coverage has grown from power alone to heavy industry and now to broader manufacturing and aviation. Emissions data collection is expanding. The price signal, while still modest, is embedded in corporate accounting and long‑term planning. The trajectory suggests incremental tightening rather than abrupt shocks.

That pattern matters at scale. When a country responsible for roughly 30 % of global emissions expands carbon‑pricing coverage from 60 % toward 80 % of its own emissions, the signal extends beyond domestic borders. The math is straightforward. Each $10 increase in carbon price applied to 10,000 million tons of covered emissions represents $100 billion in annual compliance value. Whether that value circulates through free‑allocation adjustments, auction revenue, or investment shifts, it influences capital‑allocation decisions across energy, industry, and infrastructure. The expansion of sectors into reporting and eventual pricing is not dramatic in tone, but it is structural in consequence.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...