Why It Matters

The shift confirms robust demand for cheap clean power but exposes pricing volatility, quality risks, and regulatory complexity that will dictate investment strategies and supply‑chain decisions across the PV sector.

Key Takeaways

- •2025 EU PV installations hit ~70 GW, record year

- •Global PV installations exceed 700 GW, driven by China

- •Battery storage growth adds new revenue streams worldwide

- •Module prices rising after Chinese overcapacity correction

- •EU regulations push market segmentation and “Made in Europe” demand

Pulse Analysis

The 2025 solar surge underscores a maturing global market where China remains the engine, delivering more than half of the 700 GW installed capacity. Emerging economies such as India and several African nations are scaling installations at unprecedented rates, while battery storage projects multiply to address declining PV electricity values and grid congestion. This dual‑track expansion not only diversifies revenue streams for developers but also reinforces solar’s position as the cheapest source of electricity in most regions, accelerating the energy transition.

At the same time, the industry wrestles with a painful correction. Years of overcapacity forced manufacturers, especially in China, to sell modules below production costs, eroding margins and prompting a wave of consolidation. Prices are beginning to recover, but the transition raises quality concerns as cost‑cutting measures have led to early field failures. In Europe, a complex web of 29 national regulations and upcoming "Made in Europe" procurement rules adds another layer of fragmentation, creating premium niches for higher‑quality, locally‑sourced modules while complicating cross‑border supply chains.

For investors and operators, these dynamics demand more sophisticated business models. Pure PV projects without battery storage are increasingly vulnerable to market price fluctuations, making integrated PV‑BESS solutions essential for long‑term profitability. Decision‑making will rely heavily on AI‑driven analytics to navigate regulatory nuances, raw‑material price volatility, and quality assurance. Companies that can adapt to the emerging segmented market and leverage advanced forecasting tools are poised to capture the next wave of growth as the sector targets up to 1 TW of annual installations by 2030.

The new rationale of the EU PV Market

In its first monthly column for pv magazine, the Becquerel Institute explains how solar PV continues its global expansion despite political uncertainty and market turbulence. In Europe, 2025 was a record year — but the underlying dynamics are becoming increasingly complex.

Although the final figures will not be available for several months, preliminary reports show another year of growth for the global PV market in 2025. While our preliminary numbers are well above 700 GW installed, let’s maintain a little suspense until all the data have been published and verified. One clear trend we have noticed is the decoupling between mature markets that are stagnating, sometimes at a high level, and emerging ones still booming. While Europe is stable at its higher level, the US market is in decline due to the aggressive policies of its current administration. Many established markets have not experienced growth for years, but continue to deliver regularly PV installations: Australia, Japan or Korea are part of that list. What is more interesting is the speed at which PV develops now in new geographies. And of course, China is in the driver seat, contributing to more than half of all installations globally. Those who believed that the change of remuneration in China would significantly affect the market will have to wait as it hasn't materialised yet.

Battery storage: a second structural trend

A second clear trend is the tremendous growth of battery storage, in China but also in Europe and numerous other locations. This is being driven by the decreasing value of PV electricity in some geographies, grid congestion or more lucrative business models.

Why PV keeps growing globally

These trends demonstrate a continuously growing global appetite for PV, with contrasted evolutions, but a clear growth trajectory. This is highlighted by the low cost of PV electricity, placing it as the cheapest source of electricity in most geographies, and driving its dynamic development. In addition to its cost, PV benefits from scalability and ease of deployment, making it unbeatable demand for electricity is growing and conventional sources cannot cope with the rapid increase in demand.

Hence, while some predicted that the global PV market would stagnate by 2025, it has continued to grow, driven by China and emerging markets. And this is more of the same story for years: PV intrinsic qualities are making it the natural source of electricity everywhere, without the need for sophisticated public support (unlike nuclear, for instance).

Where future global growth will come from

The potential for growth in the coming years will come from India (which could multiply its installations by a factor of 10 and follow the Chinese path), emerging countries, and new applications. From greening the desert to e-everything: new business models for PV electricity might lead to reaching 1 TW of newly installed annual capacities around 2030.

Europe: record installations, but rising concerns

In Europe, the trend continues to be more positive than many would admit. 2025 will end up as the highest year ever for PV installations, with major surprises, such as the Spanish market. With around 70 GW installed in Europe, PV has successfully coped with adverse political winds in some countries, business model changes and uncertainties related to the complex international situation until now. This is, however, not a guarantee for the future and reasons for preoccupation increase, together with the complexity of doing business in Europe.

Needless to mention the 29 regulations (Belgium counts for three) which complexify the operations in the European Union, plus the other European countries, it is a given for many years. They also constitute an opportunity for PV development: adverse political winds in one country do not affect the entire market in Europe. However, the following elements are going to make the European PV market more complex in 2026 and beyond.

Prices are up, and that won’t change the picture much

Extremely low system prices for PV systems have been reached partially thanks to extremely low PV modules prices. The unsustainability of low prices is factual, despite many commentators, especially in the downstream sector believing their providers: the massive losses of most industry actors in the PV value chain, starting from China, explicit that state of facts. The dozens of billions lost in 2024 and 2025 by most producers through the entire value chain explicit the consequences of overcapacity at every stage of the PV value chain. These overcapacities have led all actors to price their products below their own production costs, leading to a false sense of the final prices: modules are using components which can’t make their producers profitable, and especially glass and cells, while cells producers are partially compensating for losses by acquiring wafers sold below their production costs, which in turn use loss-generating polysilicon. Therefore, a module manufacturer may look profitable when using cheap cells, however, its price hides an unhealthy value chain: This cannot be considered sustainable.

This situation couldn’t last for long, and the Chinese government made the right decision to halt the bloodbath before it would destroy the entire industry. While some doubt the ability of the Chinese authorities to regulate their industry, others admit that the first signs of price recovery are now visible. This is not only coming from higher demand for PV modules: a cleansing of the value chain in China is ongoing and will lead to consolidation and a return to sustainable prices.

All manufacturers are looking for market conditions in which to sell modules at higher prices, and Europe is a potential playing field that could allow for this. Consequently, prices in Europe are going up. This remains a moving target that will be influenced in the coming months by several key indicators: demand of course, but also the fast-evolving market price of raw materials. In a complex geopolitical environment, with the USD losing ground to many competing currencies, the number of parameters to follow to forecast properly the future prices of PV modules is becoming a daunting task. The only trend on which everyone seems to agree is that PV modules will become more expensive.

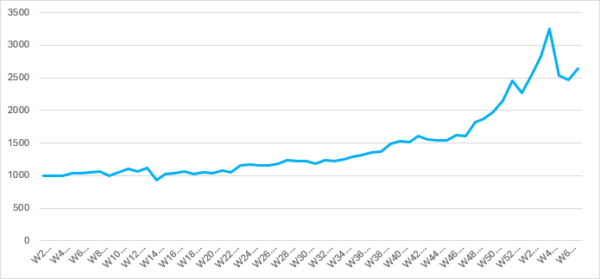

PolySi, in $/kg

Silver in $/kg

What about quality?

Persistent rumors about the increase in failures in the field of new modules should alarm everyone. While the extent of the issues should not be debated in a public document, those directly involved know that the quest to reduce production costs might have led to quality defects. The subject is touchy since few in the industry, from upstream to downstream, publicly acknowledge the extent of the problem. However, weak signals tend to confirm an increase in early failures in the field, that would require a quantification.

Some local EU manufacturers are already changing their bills of materials (BoM) by going back to thicker glass, for instance, and such an approach could lead to some market segmentation. And higher market prices. In addition, one could notice that most Chinese manufacturers are not providing guarantees for more than 12 or 15 years. While this shouldn’t be a major issue in utility-scale plants that will experience a probably repowering at these ages, it could be a totally different scenario for distributed installations, and especially residential ones. This hasn’t materialized into a real market segmentation, but this could pave the way for a two-speed market.

A market increasingly fragmented and segmented

It should not be surprising that some EU manufacturers now produce PV modules with different bills of materials, but this remains anecdotal given the volumes. More importantly, new technologies with higher efficiency are coming to the market and target higher sales prices. While this has always existed (remember SunPower 15 years ago), the price war in recent years had reduced the gap, but this could come back, with higher prices for PV modules in some segments for specific technologies, starting with Back-Contact.

The major segmentation driver might be European regulations aiming at favoring resilience: they have started in some countries to define a market for “resilient” products (read “non-chinese”). The expected “Made in Europe” regulations which might apply to public procurement-as promised by the European Commission in Q1 2026-may add a layer of complexity, in addition to the existing NZIA and environmental regulations. This could segment the market between a free market where procurement would be like what we have experienced in the last decade, and a set of smaller segments where a pile of regulations would constrain it significantly. Origin of products, environmental footprint, cybersecurity, forced labor content, and a wide range of rules decided at national level could transform these segments into a logistical nightmare for buyers, and a profitable series of niche markets for the smartest manufacturers. While this remains to be translated into really developing manufacturing projects, this could lead to a better landscape for new and existing manufacturing actors in Europe.

As recent Italian tenders shown, resilient auctions delivered PV electricity prices at 0,01 €/kWh higher than in unconstrained auctions. That single cent increase is small compared with regional electricity price spread, showing the impact on the economy and the effect on PV deployment will be limited.

To go forward

In a nutshell, market complexity is growing year on year, mostly due to the ever-increasing penetration of PV in the electricity mix: with more than 405 GW installed in the European Union at the start of this year, and as little as 200 GW of minimum power demand in some summer days, it becomes obvious that we have entered into an area where the sole competitiveness of PV electricity cannot be decoupled from electricity market prices. Business models where PV will be profitable in the long term without the support of BESS are improbable, and revenue staking with PV contributing increasing to managing the grid will become central.

Procurement will become more complex and change more frequently. With resilience requirements, made in Europe criteria, environmental constraints and quality issues, challenges are multiplying and PV development business models will also increase in complexity. AI tools that support decision-making and access to reliable, verified information will be essential to help policymakers understand the complexity of the energy transition. This, in turn, will shape how much PV can contribute in the coming years.

Author: Gaëtan Masson, CEO & Founder of Becquerel Institute

Becquerel Institute is a strategic consulting company and an applied research institute specializing in solar photovoltaics and energy transition. Becquerel Institute offers unique expertise at the crossroads of technological, economic, and political analysis. It provides strategic advice to companies in Europe, America, Asia, and Africa across all segments of the PV value chain. Founded in 2014 in Brussels, the company has regional offices in France, Italy, and Spain. It is a recognized partner in European and international research projects and actively supports international organisations and associations.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...