Minions – Stripe's Coding Agents Part 2

•February 20, 2026

0

Why It Matters

By automating routine code changes at scale, Stripe dramatically accelerates development velocity while cutting CI costs and token usage, setting a benchmark for AI‑augmented software engineering.

Key Takeaways

- •1,300+ weekly PRs generated entirely by minions

- •Devboxes launch in 10 seconds, enabling hot, isolated environments

- •Blueprints blend deterministic steps with flexible LLM loops

- •Toolshed offers 500 MCP tools for shared agent capabilities

- •Automated feedback loops reduce CI cycles and token costs

Pulse Analysis

Stripe’s minions illustrate how large enterprises can harness LLM coding agents without sacrificing safety or speed. By leveraging devboxes—standardized, pre‑warmed EC2 instances—Stripe provides each agent with a clean, isolated sandbox that mirrors the environment human engineers use daily. This hot‑ready infrastructure eliminates the overhead of provisioning, ensures reproducible builds, and prevents agents from inadvertently accessing privileged resources, a critical factor when scaling autonomous code generation across thousands of repositories.

The core innovation lies in the blueprint orchestration model, which fuses deterministic workflow nodes with the adaptive reasoning of LLM loops. Deterministic steps, such as linting or branch pushes, execute predictably, conserving token budgets and reducing error rates. Meanwhile, agentic nodes handle ambiguous tasks like implementing features or fixing CI failures, benefitting from the flexibility of large language models. This hybrid approach not only streamlines token consumption but also enhances overall system reliability, as predictable components act as guardrails for the more exploratory AI actions.

Integrating the Model Context Protocol through the internal Toolshed service further amplifies the minions’ capabilities. With nearly 500 curated tools—ranging from internal documentation lookups to build status queries—agents can retrieve dynamic context without overloading their prompt windows. Security controls restrict destructive actions, and a feedback‑centric CI loop ensures that most issues are resolved locally before a second CI pass. The result is a faster, lower‑cost development pipeline that empowers engineers to focus on high‑value work, while the AI handles repetitive coding tasks at scale.

Minions – Stripe's Coding Agents Part 2

Recap of [Part 1](https://stripe.dev/blog/minions-stripes-one-shot-end-to-end-coding-agents)

As a recap of Part 1 in this blog miniseries, minions are a homegrown unattended agentic coding flow at Stripe. Over 1,300 Stripe pull requests (up from 1,000 as of Part 1) merged each week are completely minion‑produced, human‑reviewed, but containing no human‑written code.

If you haven’t read Part 1, we recommend checking that out first to understand the developer experience of using minions. In this post, we’ll dive deeper into some more details of how they’re built, focusing on the Stripe‑specific portions of the minion flow.

Devboxes, hot and ready

For maximum effectiveness, unattended agent coding at scale requires a cloud developer environment that’s parallelizable, predictable, and isolated. Humans should be able to give many agents logically separate work. Agents should have clean environments and working directories: it unnecessarily wastes tokens on resolution if agents are interfering with one another’s changes. Full autonomy also requires the agent to be systematically isolated from acting destructively over privileged or sensitive machines, especially with a human’s personal credentials.

It’s challenging to get agents running on a developer’s laptop with all these properties. Containerization or git worktrees can help, but they’re hard to combine and it’s fundamentally difficult to build local agents that have all the power of a developer’s shell but are appropriately constrained.

Minions at Stripe get these properties by default, however, by running on the same standard developer environment that Stripe engineers use: the devbox.

A Stripe devbox is an AWS EC2 instance that contains our source code and runs services under development. Most human‑written Stripe code is already produced within an IDE that’s remotely connected to a devbox via SSH. In DevOps terminology, devboxes are “cattle, not pets”: they’re standardized and easy to replace, rather than bespoke and long‑lived.

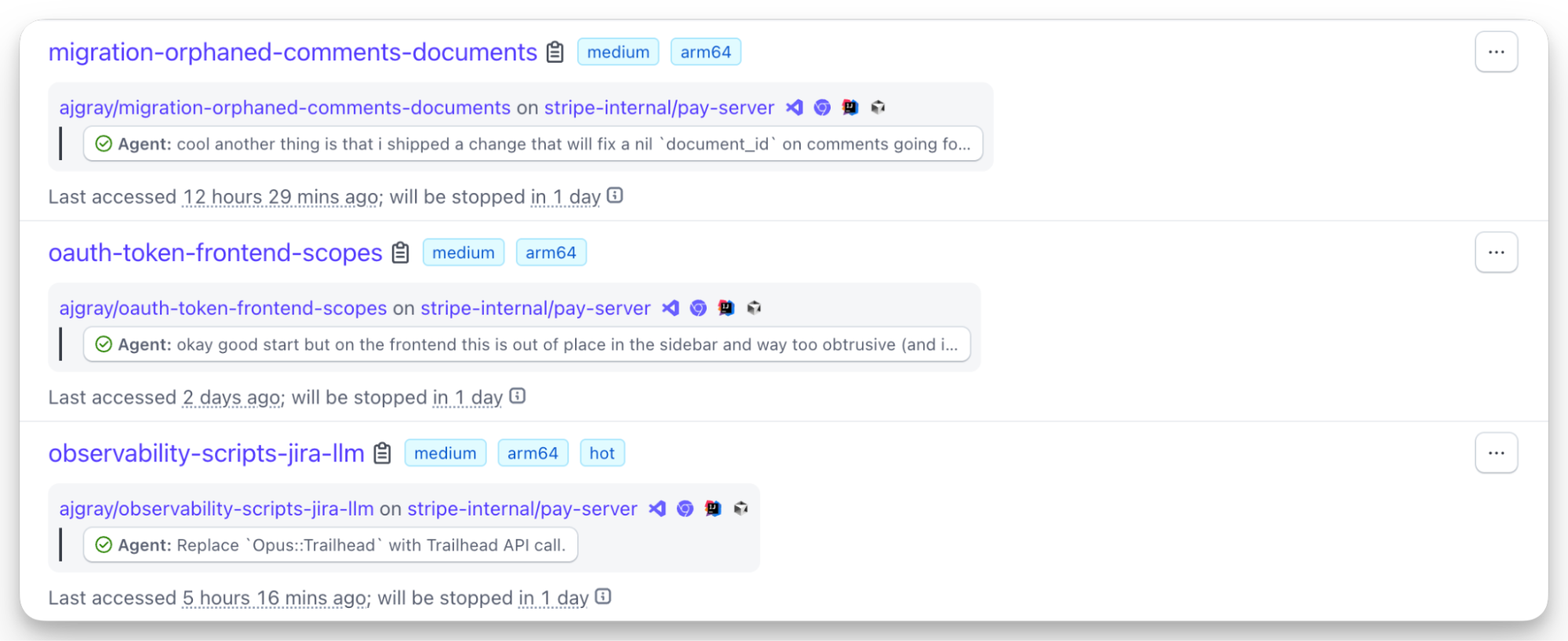

Many engineers use one devbox per task—a Stripe engineer might have half a dozen running at a time.

“A snippet of an engineer’s list of active devboxes, with minion runs.”

We want it to feel effortless to spin up a new devbox, so we aim for it to be ready within 10 seconds. To achieve this “hot and ready” standard, we proactively provision and warm up a pool of devboxes so they are ready when a developer wants them. This includes cloning gigantic git repositories, warming Bazel and type‑checking caches, starting code‑generation services that continually run on devboxes, and more. After 10 seconds, the devbox owner has a box checked out to a recent copy of master across all of Stripe’s main repos, which is immediately ready to open a REPL, run a test, make a code change and type‑check it, or start a web service.

We built out devboxes for the needs of human engineers, long before LLM coding agents existed. As it turns out, parallelism, predictability, and isolation were also very desirable properties as well for Stripe engineers to be able to work most effectively. What’s good for humans is good for agents, and building on this infrastructural primitive paid dividends as a natural home for LLM agents.

The agent

In contrast to devboxes that already powered human development, our agent harness was custom‑built for the minions use case.

In late 2024, as coding agents emerged across the industry, we internally forked Block’s goose—one of the first widely used coding agents—and customized it to work within Stripe’s LLM infrastructure. Over time, we focused our feature development of goose on the needs of minions, rather than those of human‑supervised tools: that’s a use case that’s well‑filled by third‑party tools such as Cursor and Claude Code, which are already made available to our engineers.

In fact, the most unique aspect of minions is the absence of a supervisory human. Off‑the‑shelf local coding agents are usually optimized for working through code changes as a companion to engineers, typically with one “looking over its shoulder,” so to speak. Minions, however, are fully unattended, so our agent harness can’t use human‑facing features such as interruptibility or human‑triggered commands to initiate or steer the agent run.

On the flip side, the quarantined devbox environment means that the agent doesn’t need confirmation prompts; any mistakes an agent might make are confined to the limited blast radius of one devbox, so we can safely run the agent with full permissions and skip confirmation prompts.

We can also dial in optimizations precisely tuned to Stripe’s development flow. We’ve made many small optimizations based on the particulars of Stripe’s systems. A larger optimization—which turned out to be more fundamental to our implementation of minions—is the notion of a blueprint.

Blueprints

The most common primitives for orchestrating an LLM flow are workflows and agents. A workflow is an LLM system that operates via a fixed graph of steps, where each node in the graph is responsible for a narrowly scoped portion of the overall goal, and predefined edges control the execution flow between these discrete nodes.

An agent is typically a simpler “loop with tools” orchestration pattern, where the LLM relies on its own judgment to repeatedly call the tools at its disposal and decide—based on the results of those tool calls—what to do next.

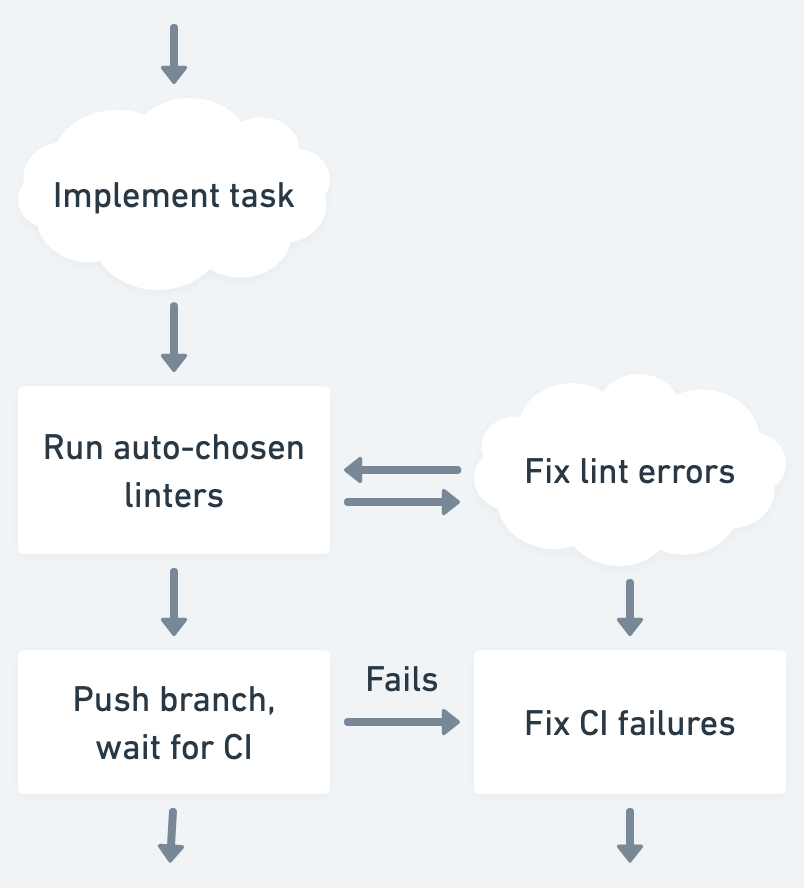

Minions are orchestrated with a primitive we call blueprints. Blueprints are workflows defined in code that direct a minion run. Blueprints combine the determinism of workflows with agents’ flexibility in dealing with the unknown: a given node can run either deterministic code or an agent loop focused on a task. In essence, a blueprint is like a collection of agent skills interwoven with deterministic code so that particular subtasks can be handled most appropriately.

In the blueprint that powers minions, for example, there are agent‑like nodes with labels such as “Implement task” or “Fix CI failures.” Those agent nodes are given wide latitude to make their own decisions based on input. However, the blueprint also has nodes with labels such as “Run configured linters” or “Push changes,” which are fully deterministic: those particular nodes don’t invoke an LLM at all—they just run code.

Thus, blueprints are a way to guarantee certain subtasks are completed deterministically within the agentic run. The minion blueprint ends up looking like a state machine that intermixes deterministic code nodes and free‑flowing agent nodes.

Example blueprint. Deterministic nodes are indicated with rectangles, and agentic subtasks are indicated with the cloud shape.

In our experience, writing code to deterministically accomplish small decisions we can anticipate—such as “always lint changes at the end of a run”—saves tokens (and CI costs) at scale and gives the agent a little less opportunity to get things wrong. In aggregate, we find that “putting LLMs into contained boxes” compounds into system‑wide reliability upside. Blueprint machinery makes context engineering of these subagents easy, whether that consists of constraining tools, modifying system prompts, or simplifying the conversation context as required for the subtask at hand.

Individual teams can also set up blueprints optimized for their specialized needs. For example, we’ve had teams build custom blueprints to encode running tricky LLM‑assisted migrations across the codebase that couldn’t be accomplished with a straightforward fully deterministic codemod.

Context gathering: Rule files

In a large codebase such as Stripe’s, an agent set loose without any guidance might encounter trouble following best practices or using the proper libraries, even with good linters. To help with this issue, various agent rule formats—think CLAUDE.md or AGENTS.md—allow agents to “learn” about the codebase automatically as they traverse its directory structure.

Due to the size of our repositories, we use unconditional global rules very judiciously, since otherwise the agent’s whole context window would fill with rules before the agent even starts. Instead, we almost exclusively give minions context from files that are scoped to specific subdirectories or file patterns, automatically attached as the agent traverses the filesystem.

From our perspective, it’s best to avoid duplication of rule files in favor of our agent reading the same context that human‑directed agents use. Given that, we standardized on a popular rule format that supported these features—Cursor’s rule format—and modified our harness to allow minions to read those rules in addition to a previous homegrown format.

We also now sync our Cursor rules into a format that Claude Code can read as well, so that our three most popular coding agents (minions, Cursor, and Claude Code) can all benefit from the guidance that lives in rule files that Stripe engineers are scaffolding in our codebase.

Context gathering: MCP

Reading from a filesystem works well for static context gathering, but agents frequently need to dynamically fetch information using networked tool calls. In particular, to fully hydrate user requests, minions need to retrieve information such as internal documentation, ticket details, build statuses, code intelligence, and more. Upon release, the Model Context Protocol (MCP) quickly became the industry‑wide standard for networked tool calls, and we moved to integrate minions with it.

Stripe has built or integrated lots of agents running on different frameworks: a no‑code internal agent builder, custom agents running on dedicated services, third‑party off‑the‑shelf agents, command‑line agentic tools and other coding agents, and agentic Slack bots. All these agents, not just minions, needed MCP capabilities, often including overlapping sets of common tools.

To support all of these, we built a centralized internal MCP server called Toolshed, which makes it easy for Stripe engineers to author new tools and make them automatically discoverable to our agentic systems. All our agentic systems are able to use Toolshed as a shared capability layer; adding a tool to Toolshed immediately grants capabilities to our whole fleet of hundreds of different agents.

Toolshed currently contains nearly 500 MCP tools for internal systems and SaaS platforms we use at Stripe. Agents perform best when given a “smaller box” with a tastefully curated set of tools, so we configure different agents to request only a subset of Toolshed tools relevant to their task. Minions are no exception and are provided an intentionally small subset of tools by default, although per‑user customizability allows engineers to configure additional thematically grouped sets of tools for their own minions to use.

Since minions operate autonomously with full freedom to call their MCP tools, we also have an internal security control framework that ensures they can’t use their tools to perform destructive actions. As a first line of defense, though, our devboxes already run in our QA environment, and consequently, minions don’t have access to real user data, Stripe’s production services, or arbitrary network egress. This is no accident: we built isolated devboxes deliberately, so humans have an environment they can experiment within safely. But, as with so much else, a development environment that’s safe for humans has proven to be just as useful for minions.

… and iterate

While we build minions with the goal of one‑shotting their tasks, it’s key to give agents automated feedback that they can iterate against to make progress. Stripe’s enormous pre‑existing battery of tests—over three million of them—can provide this feedback. However, while a pushed branch will run all relevant tests in CI, we don’t want to rely too heavily on CI for all our code feedback.

We try to operate under the principle of “shifting feedback left” when thinking about developer productivity. That phrase means that if we know an automated check will fail CI, it’s best if it’s also enforced in the IDE and presented to the engineer right away, since that’s the fastest way to provide feedback to the user.

For example, we have pre‑push hooks to fix the most common lint issues. A background daemon precomputes lint‑rule heuristics that apply to a change and caches the results of running those linters, so developers can usually get lint fixes in well under a second on a push.

Minions naturally integrate with this framework as well, so they don’t have to waste tokens or CI minutes by iterating against an auto‑formatter or similar. We run a subset of linters as a deterministic node within the agent devloop blueprint, and loop on that lint node locally before pushing an agent’s branch, so that the branch has a fair shot at passing CI the first time around.

It’s infeasible to run all tests locally, so we also include one iteration against the full CI suite into the standard minion blueprint. After a minion pushes a change, we run CI and auto‑apply any autofixes for failing tests. If there are failures with no autofix, we send the failure back to a blueprint agent node and give the minion one more chance to fix the failing test locally. After the second push and CI run, we send the branch back to its human operator for manual scrutiny.

Why have only one or two rounds of CI? There’s a balancing act between speed and completeness here; CI runs cost tokens, compute, and time, and we think there are diminishing marginal returns if an LLM is running against indefinitely many rounds of a full CI loop. We feel that our policy strikes a good balance between the competing considerations here.

In conclusion

Minions are just one way that Stripe is using AI to accelerate our engineers, but we think they’re a great example of how we’re able to blend industry‑standard concepts—such as agent harnesses and MCP—with our own mix of internal tooling and infrastructure that our engineers have relentlessly tuned over the years to maximize developer productivity.

Whether it’s through improving documentation, developer environments, or iteration loops, we’ve found time and time again that our investments in human developer productivity over time have returned to pay dividends in the world of agents.

Minions have already changed the landscape of software engineering at Stripe. We’re continuing to make them better as we build out our agent experience with the latest and greatest from the industry at large, adapted to work at Stripe scale. Combined with the taste and expertise we’ve learned in hard‑fought battles for human developer experience, we’ll make them the best they can be.

Interested in working with, or on, minions? Stripe is hiring.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...