Why It Matters

Europe’s pivot to independent, issue‑driven engagement reshapes global trade and climate collaboration, reducing reliance on U.S. leadership and redefining power balances.

Key Takeaways

- •EU pursues strategic autonomy, engaging China independently

- •Leaders from West and Asia visiting Beijing signal issue‑based ties

- •CPTPP becomes post‑bloc platform linking EU, UK, China

- •Green tech collaboration accelerates global decarbonisation

- •Divergences persist in market access and industrial policy

Pulse Analysis

The erosion of the post‑Cold‑War order has forced the European Union to reconsider its reliance on Washington and to chart a more autonomous foreign policy. By hosting a series of high‑profile visits—from France’s Emmanuel Macron to Canada’s Mark Carney—the EU signals a willingness to negotiate with Beijing outside traditional security alliances. This diplomatic outreach reflects a broader strategic autonomy agenda, where Europe leverages its regulatory clout and economic weight to shape global standards on its own terms.

Issue‑based cooperation is now the operative model, as illustrated by the evolving Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans‑Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Once a U.S.‑led trade architecture, the CPTPP is being reshaped by middle powers, with the United Kingdom already a member, China applying for accession, and the EU courting closer ties. The agreement’s focus on rules, standards and mutual economic interest sidesteps ideological bloc divisions, creating a flexible platform for trade, technology and supply‑chain coordination. Parallel developments in green technology—solar, wind, batteries—show Europe and China capitalising on each other's strengths to accelerate decarbonisation, while jointly advocating for reforms to the World Trade Organization.

Despite growing collaboration, friction points remain. Disagreements over market access, industrial subsidies and trade remedies indicate that the EU will continue to act as a balancing pole, preserving security ties with the United States while engaging China where interests align. This nuanced stance allows Europe to uphold liberal democratic values without alienating a key economic partner. As multipolar governance solidifies, the EU‑China relationship will likely become a template for selective, issue‑driven alliances that transcend traditional bloc politics.

Beyond Blocs

Europe and China will not align nor compete, but selectively cooperate · By Wang Huiyao, founder and president of the Center for China and Globalization · February 10 2026, 1:45 PM

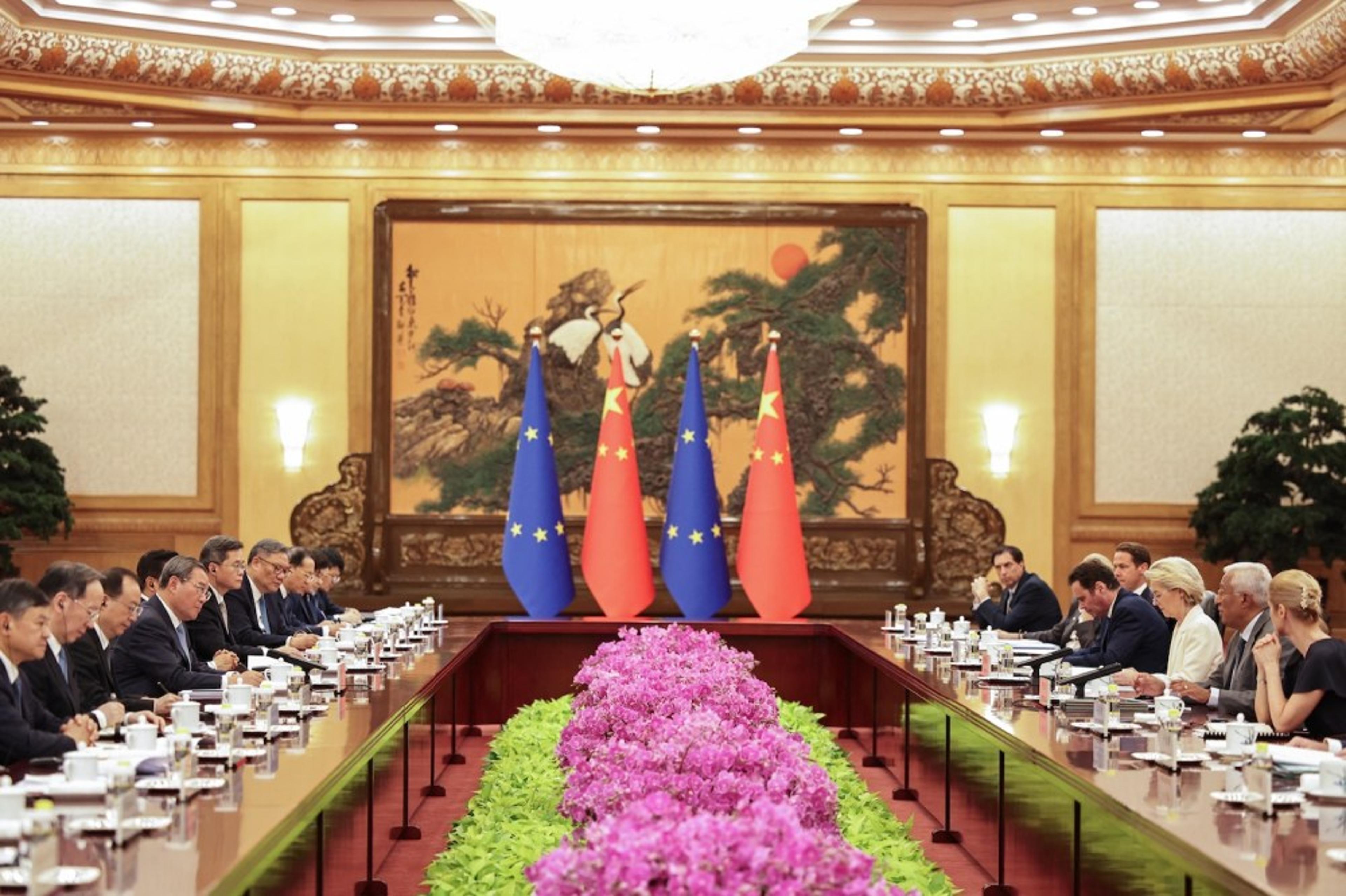

The opening remarks of the 25th European Union‑China Summit at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on July 24 2025. Andrés Martínez Casares / Pool / AFP via Getty Images

It is no longer a China versus the West, nor the West versus the rest. In fact, we no longer live in a world of blocs at all. Instead, we are moving into a world of issues‑based cooperation.

This is perhaps clearest from the cavalcade of leaders who are visiting Beijing. Already, French President Emmanuel Macron, South Korean President Lee Jae‑myung, Taoiseach of Ireland Micheál Martin, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, and U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer have all visited China in recent months. German Chancellor Friedrich Merz is expected to begin his visit in February. Even U.S. President Donald Trump is set to visit in April.

At its core, these visits are a response to the erosion of the post‑Cold‑War order, whose death became the main topic of discussion at the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. With Washington no longer serving as a reliable steward of the multilateral system, the European Union’s long‑standing pursuit of strategic autonomy is moving from rhetoric to practice. The result will be Europe’s emergence as an independent pole, one defined by regulatory power, economic gravity, and normative influence.

What has changed most fundamentally is not the disappearance of values but their role in global alignment. For much of the post‑Cold‑War period, perceptions of shared values sustained bloc loyalty, even when material interests diverged. It was a “community of shared values” that created the G‑7 and NATO and that saw the Western world intervene together in the Balkans in 1999, fight in Afghanistan after 9/11, and join forces to support Ukraine.

Over the past decade, this same Euro‑Atlantic community was gradually moving toward a consensus that China was hostile to the community of liberal Western states and should be isolated with a cordon sanitaire. But even that unity is now at an end. With Washington attacking Europe rather than trying to rally it, Canada, the U.K., and the EU have all begun to reach out to China on their own terms.

Yet despite some predictions, this will not result in lasting Chinese‑European alignment. Instead, the world is entering a contested phase of multipolar governance without bloc‑based communities. To borrow the words of Mark Carney, there are now “different coalitions for different issues based on common values and interests.” Climate cooperation does not need to follow security alliances. Trade governance does not align neatly with bloc‑based technological standards. Artificial intelligence, supply chains, and health security each generate their own constellations of cooperation.

Trade governance offers a clear illustration of this shift. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans‑Pacific Partnership, once conceived as a U.S.–led instrument of regional economic statecraft, is now effectively stewarded by middle powers. With the United Kingdom already acceding, China applying, and the European Union seeking its own closer affiliation, the agreement has evolved into a post‑bloc platform shaped less by ideology than by rules, standards, and mutual economic interest.

The same dynamics can be seen in other critical policy domains. China’s green industrial capacity—spanning solar, wind, batteries, electric mobility, and grid equipment—has driven global decarbonisation. For years the United States cajoled its allies to limit uptake of Chinese green technology. Now Europe and Canada are freed from the blinders of bloc‑shaped politics and increasingly able to engage with Chinese capacity and expertise on their own terms.

Similarly, the European Union and China both remain committed to multilateral governance and institutional reform. Both maintain that they share a responsibility to uphold an international rules‑based order rooted in the United Nations and to advance reform of the World Trade Organization, including the restoration of its dispute‑settlement function and the Multi‑Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement.

But amid this convergence, areas of divergence remain, including trade remedies, market access, and industrial policy. This is why, despite recent tangible improvements in EU‑China dialogue, the European Union will continue to act primarily as a balancing pole. The member nations of the EU still maintain security ties with Washington, and the EU itself is engaging with China on its own terms rather than joining a new camp.

In this emerging world, the EU can hold on to the values that it does not share with China while still cooperating on shared interests.

Wang Huiyao is the founder and president of the Center for China and Globalization, a nongovernmental think tank based in Beijing. Wang often advises the Chinese government.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...