Why It Matters

The technology lowers the expertise barrier for product design, opening rapid, sustainable prototyping to non‑engineers and reshaping localized manufacturing.

Key Takeaways

- •Text prompts generate 3D designs via dual generative AI models

- •Vision‑language model assigns panels based on function and geometry

- •Robot assembles objects from reusable prefabricated parts

- •User feedback loop yields >90% preference in study

- •System promises sustainable, on‑demand manufacturing for complex items

Pulse Analysis

The convergence of generative AI and robotics is redefining how physical products are conceived. By interpreting plain‑language requests, the MIT system bypasses traditional CAD workflows, which often demand specialized training. The dual‑model architecture—first generating a coherent 3‑D mesh, then using a vision‑language model to allocate functional components—creates a seamless pipeline from idea to tangible prototype. This approach not only accelerates design cycles but also democratizes creation, allowing designers, hobbyists, and small businesses to materialize concepts without deep engineering expertise.

A standout feature is the human‑in‑the‑loop mechanism that lets users iteratively refine outputs. Prompt adjustments such as “only use panels on the backrest” are instantly processed, producing updated geometry and assembly instructions. The study’s 90% preference rating underscores the system’s ability to meet aesthetic and functional expectations better than rule‑based or random placement algorithms. Moreover, the use of prefabricated, reusable components reduces material waste and simplifies logistics, aligning with circular economy principles.

Looking ahead, the platform could transform sectors that rely on rapid, custom fabrication—ranging from aerospace components to architectural installations. By expanding the library of modular parts to include hinges, gears, and diverse materials, the technology promises to handle increasingly complex designs. In the longer term, household‑level manufacturing becomes plausible, cutting shipping costs and carbon footprints. As generative AI models continue to improve, their integration with physical assembly robots may become a cornerstone of on‑demand, sustainable production ecosystems.

“Robot, make me a chair”

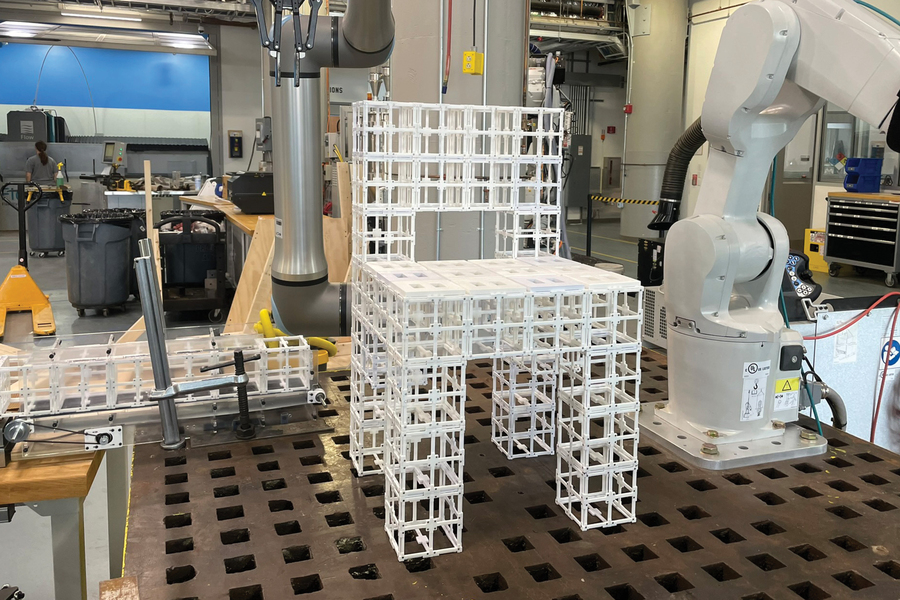

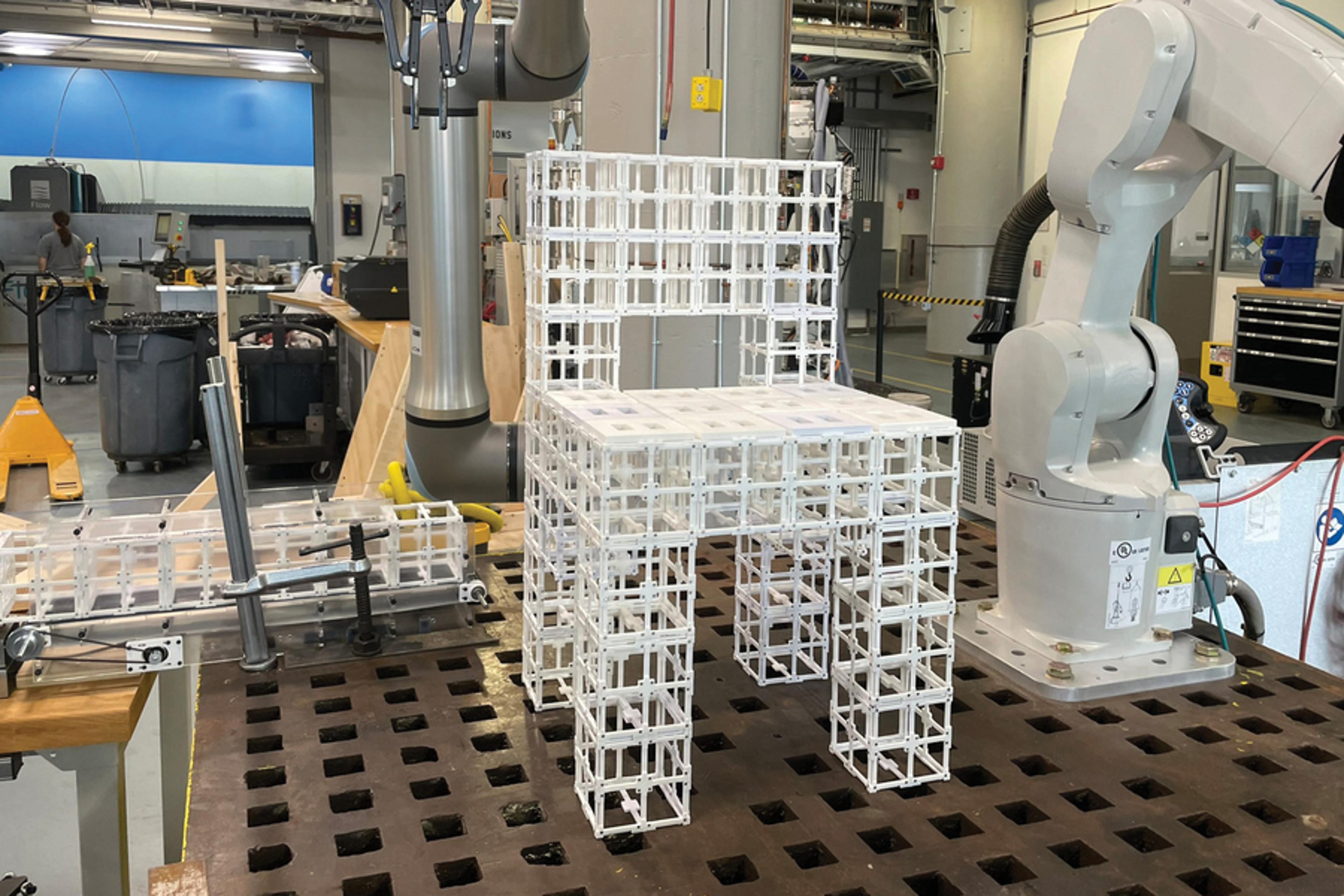

Given the prompt “Make me a chair” and feedback “I want panels on the seat,” the robot assembles a chair and places panel components according to the user prompt. Image credit: Courtesy of the researchers.

Given the prompt “Make me a chair” and feedback “I want panels on the seat,” the robot assembles a chair and places panel components according to the user prompt. Image credit: Courtesy of the researchers.

By Adam Zewe

Computer-aided design (CAD) systems are tried-and-true tools used to design many of the physical objects we use each day. But CAD software requires extensive expertise to master, and many tools incorporate such a high level of detail they don’t lend themselves to brainstorming or rapid prototyping.

In an effort to make design faster and more accessible for non-experts, researchers from MIT and elsewhere developed an AI-driven robotic assembly system that allows people to build physical objects by simply describing them in words.

Their system uses a generative AI model to build a 3D representation of an object’s geometry based on the user’s prompt. Then, a second generative AI model reasons about the desired object and figures out where different components should go, according to the object’s function and geometry.

The system can automatically build the object from a set of prefabricated parts using robotic assembly. It can also iterate on the design based on feedback from the user.

The researchers used this end-to-end system to fabricate furniture, including chairs and shelves, from two types of premade components. The components can be disassembled and reassembled at will, reducing the amount of waste generated through the fabrication process.

They evaluated these designs through a user study and found that more than 90 percent of participants preferred the objects made by their AI-driven system, as compared to different approaches.

While this work is an initial demonstration, the framework could be especially useful for rapid prototyping complex objects like aerospace components and architectural objects. In the longer term, it could be used in homes to fabricate furniture or other objects locally, without the need to have bulky products shipped from a central facility.

“Sooner or later, we want to be able to communicate and talk to a robot and AI system the same way we talk to each other to make things together. Our system is a first step toward enabling that future,” says lead author Alex Kyaw, a graduate student in the MIT departments of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) and Architecture.

Kyaw is joined on the paper by Richa Gupta, an MIT architecture graduate student; Faez Ahmed, associate professor of mechanical engineering; Lawrence Sass, professor and chair of the Computation Group in the Department of Architecture; senior author Randall Davis, an EECS professor and member of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL); as well as others at Google Deepmind and Autodesk Research. The paper was recently presented at the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems.

Generating a multicomponent design

While generative AI models are good at generating 3D representations, known as meshes, from text prompts, most do not produce uniform representations of an object’s geometry that have the component-level details needed for robotic assembly.

Separating these meshes into components is challenging for a model because assigning components depends on the geometry and functionality of the object and its parts.

The researchers tackled these challenges using a vision-language model (VLM), a powerful generative AI model that has been pre-trained to understand images and text. They task the VLM with figuring out how two types of prefabricated parts, structural components and panel components, should fit together to form an object.

“There are many ways we can put panels on a physical object, but the robot needs to see the geometry and reason over that geometry to make a decision about it. By serving as both the eyes and brain of the robot, the VLM enables the robot to do this,” Kyaw says.

A user prompts the system with text, perhaps by typing “make me a chair,” and gives it an AI-generated image of a chair to start.

Then, the VLM reasons about the chair and determines where panel components go on top of structural components, based on the functionality of many example objects it has seen before. For instance, the model can determine that the seat and backrest should have panels to have surfaces for someone sitting and leaning on the chair.

It outputs this information as text, such as “seat” or “backrest.” Each surface of the chair is then labeled with numbers, and the information is fed back to the VLM.

Then the VLM chooses the labels that correspond to the geometric parts of the chair that should receive panels on the 3D mesh to complete the design.

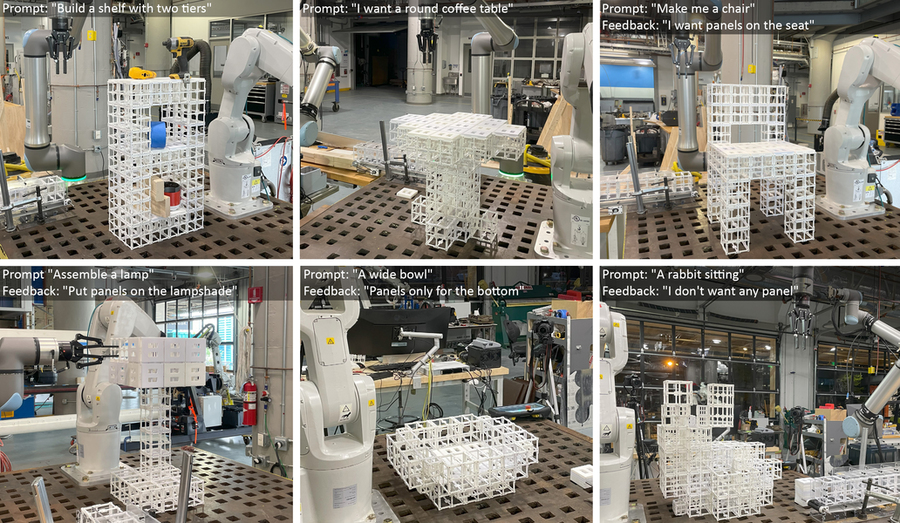

These six photos show the Text to robotic assembly of multi-component objects from different user prompts. Credit: Courtesy of the researchers.

These six photos show the Text to robotic assembly of multi-component objects from different user prompts. Credit: Courtesy of the researchers.

Human-AI co-design

The user remains in the loop throughout this process and can refine the design by giving the model a new prompt, such as “only use panels on the backrest, not the seat.”

“The design space is very big, so we narrow it down through user feedback. We believe this is the best way to do it because people have different preferences, and building an idealized model for everyone would be impossible,” Kyaw says.

“The human‑in‑the‑loop process allows the users to steer the AI‑generated designs and have a sense of ownership in the final result,” adds Gupta.

Once the 3D mesh is finalized, a robotic assembly system builds the object using prefabricated parts. These reusable parts can be disassembled and reassembled into different configurations.

The researchers compared the results of their method with an algorithm that places panels on all horizontal surfaces that are facing up, and an algorithm that places panels randomly. In a user study, more than 90 percent of individuals preferred the designs made by their system.

They also asked the VLM to explain why it chose to put panels in those areas.

“We learned that the vision language model is able to understand some degree of the functional aspects of a chair, like leaning and sitting, to understand why it is placing panels on the seat and backrest. It isn’t just randomly spitting out these assignments,” Kyaw says.

In the future, the researchers want to enhance their system to handle more complex and nuanced user prompts, such as a table made out of glass and metal. In addition, they want to incorporate additional prefabricated components, such as gears, hinges, or other moving parts, so objects could have more functionality.

“Our hope is to drastically lower the barrier of access to design tools. We have shown that we can use generative AI and robotics to turn ideas into physical objects in a fast, accessible, and sustainable manner,” says Davis.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...