NASA Chief: Artemis Moon Landing Is Litmus Test for ‘American Exceptionalism’

•February 10, 2026

0

Companies Mentioned

Why It Matters

Landing before China would reinforce U.S. leadership in space and validate NASA’s technical roadmap, while workforce reforms aim to secure critical expertise for future deep‑space missions.

Key Takeaways

- •Artemis III now targeted for 2028, not 2024

- •NASA re‑evaluating SpaceX lander due to refueling complexity

- •Competition with China accelerates lunar program timelines

- •75% of NASA workforce currently contracted, shift to civil servants

- •On‑orbit propellant transfer key for sustained lunar presence

Pulse Analysis

The Artemis program has become more than a scientific endeavor; it is a geopolitical signal. As China races toward a 2030 crewed lunar landing, the United States faces pressure to demonstrate that its space infrastructure remains cutting‑edge. Delaying Artemis III to 2028 compresses the timeline, forcing NASA to streamline development and leverage competition as a catalyst for innovation. This urgency underscores the broader narrative that space achievements are intertwined with national prestige and strategic advantage.

Technical hurdles dominate the conversation, especially the choice of lunar lander. NASA’s original contract with SpaceX relies on a Starship variant that must perform on‑orbit cryogenic methane refueling—a capability never demonstrated in space. Critics argue that this adds risk and complexity, prompting the agency to solicit alternative designs from SpaceX and Blue Origin that avoid refueling. The outcome of this procurement review will shape not only the Artemis III mission but also the architecture of future lunar bases, where reliable propellant transfer could become a cornerstone of sustained presence.

Beyond hardware, Isaacman’s recent workforce directive signals a cultural shift within the agency. With roughly three‑quarters of NASA’s labor outsourced, the push to convert critical flight‑test and operations roles to civil servants aims to rebuild in‑house expertise. This move is intended to safeguard mission continuity, reduce reliance on external contractors, and ensure that the agency retains the institutional knowledge needed for long‑term exploration goals. Together, these strategic, technical, and human‑resource adjustments illustrate how Artemis serves as a barometer for America’s broader space ambitions.

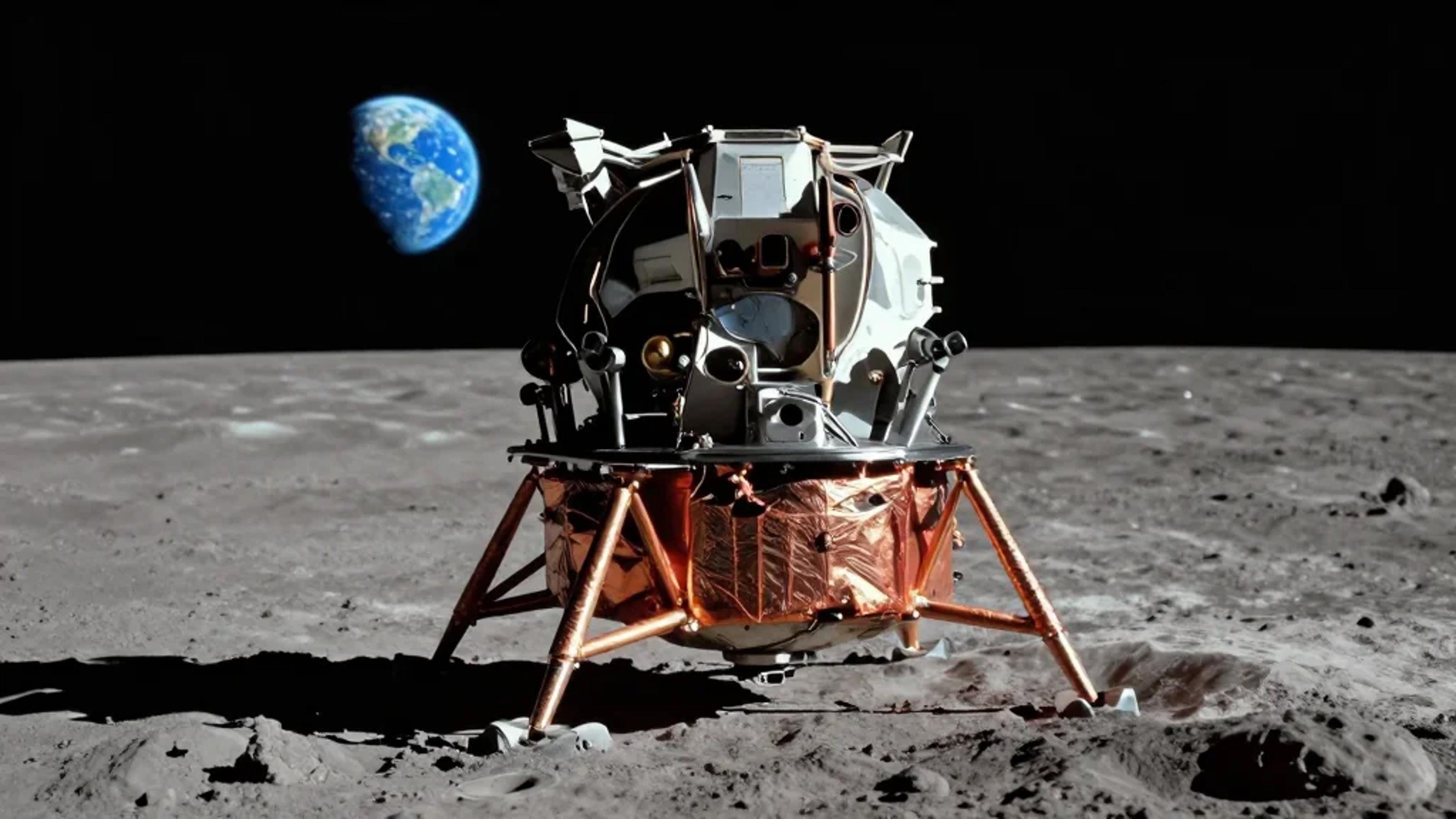

NASA chief: Artemis moon landing is litmus test for ‘American exceptionalism’

RESTON, Va. — The stakes for NASA’s Artemis lunar program are higher than just returning U.S. astronauts to the surface of the moon, according to Administrator Jared Isaacman. Failure to do so before China lands its own astronauts would “call into question American exceptionalism,” he told a crowd today at the Defense and Intelligence Space Conference here.

A U.S. failure in this area should trigger questions about “what else is broken? What else is wrong?” he said. “I would expect there’d be a lot of congressional hearings on that, because it calls almost everything we are pursuing across all these emerging and important technological domains into question.”

The White House in December delayed the target date for the Artemis III landing to 2028, four years behind the date set when the Artemis program was established during the first Trump administration, and just two years before China’s 2030 target for its own landing.

In some sense, Isaacman said, this competition has incentivized NASA to adapt and shorten its own timelines. “Competition on a geopolitical level is a good thing as well if that causes us to challenge the status quo, which is desperately needed right now, and unleash the potential that we have as a nation.”

The agency last year decided to revisit the contract for the Artemis III lander, awarded to SpaceX in 2021. U.S. lawmakers and observers have voiced concern that SpaceX’s architecture is too complicated because it requires the Starship lander to dock with multiple tanker spacecraft to fill up its fuel tanks with cryogenic methane, a technique that has never been demonstrated on‑orbit. NASA in October solicited alternative lander architectures from SpaceX and Blue Origin, the contractor for a future Artemis landing, that reportedly do not require refueling.

Isaacman today emphasized the need to achieve the Artemis III landing as quickly as possible, but noted that on‑orbit propellant transfer operations will play a central role in NASA’s long‑term goal to establish at least one lunar surface base to achieve a “sustained presence.”

“That will be a light switch moment for humanity,” as well as “a key enabling capability for peaceful exploration of space, but certainly national security reasons,” he said.

Also central to Artemis and other “absolute needle‑moving objectives,” he said, is rebuilding internal expertise within the agency, the goal of a workforce directive he issued last week. Within 30 days, NASA center directors are to prepare assessments of which roles and functions currently done by contract employees should be converted to civil servant positions.

“One thing that I thought was rather surprising is — and I don’t know how applicable this is across other government agencies — but 75 % of our workforce is contracted,” Isaacman said. That makes sense for some functions, like cybersecurity, he said, but “I would think that when it comes to flight test operations, launching rockets and on‑orbit operations, that would be an area of great expertise” for NASA to have in‑house.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...