Satellite Manufacturers See Emerging Market for ‘Mini-Constellations’

•February 10, 2026

0

Companies Mentioned

Why It Matters

Mini‑constellations diversify the satellite market, reducing dependence on a few large operators and opening new revenue streams for small‑sat manufacturers. This shift accelerates sovereign capabilities and specialized services across both public and private sectors.

Key Takeaways

- •Demand rising for 5‑200 satellite mini‑constellations

- •Governments seek sovereign communications, avoid megaconstellation dependence

- •Companies aim to lower data service costs with custom fleets

- •Manufacturers target economies of scale beyond one‑off builds

- •Mini‑constellations enable rapid‑revisit imaging and niche services

Pulse Analysis

The satellite landscape has long been dominated by a handful of megaconstellations that promise global coverage at scale. Yet a growing cohort of governments and corporations is reassessing that model, favoring smaller, purpose‑built fleets that can deliver sovereign communications, lower latency, and mission‑specific data. These "mini‑constellations"—typically 5 to 300 satellites—offer a middle ground: enough nodes for continuous regional coverage while preserving control over architecture, frequency allocation, and security protocols. This nuanced demand reflects broader geopolitical concerns and a desire for cost‑predictable services that large operators cannot always guarantee.

For manufacturers, the shift translates into a strategic pivot from bespoke, one‑off builds to semi‑mass‑production lines. Companies like Terran Orbital and GomSpace are investing in modular platforms, standardized bus designs, and automated assembly to achieve economies of scale without sacrificing customization. The ability to produce dozens or hundreds of identical units reduces unit cost, shortens lead times, and improves reliability through repeatable processes. At the same time, supply‑chain considerations—such as sourcing propulsion, power, and antenna subsystems—become critical as firms balance volume with the flexibility required for varied customer specifications.

Industry analysts predict that mini‑constellations will carve out a distinct market segment, prompting regulators to refine licensing frameworks and spectrum management policies. As more nations launch sovereign fleets, partnerships between traditional aerospace firms and emerging space‑tech startups are likely to accelerate, fostering innovation in propulsion, on‑orbit servicing, and AI‑driven data analytics. Ultimately, the rise of mini‑constellations could democratize access to space‑based services, spur competition, and reshape the economics of satellite communications for the next decade.

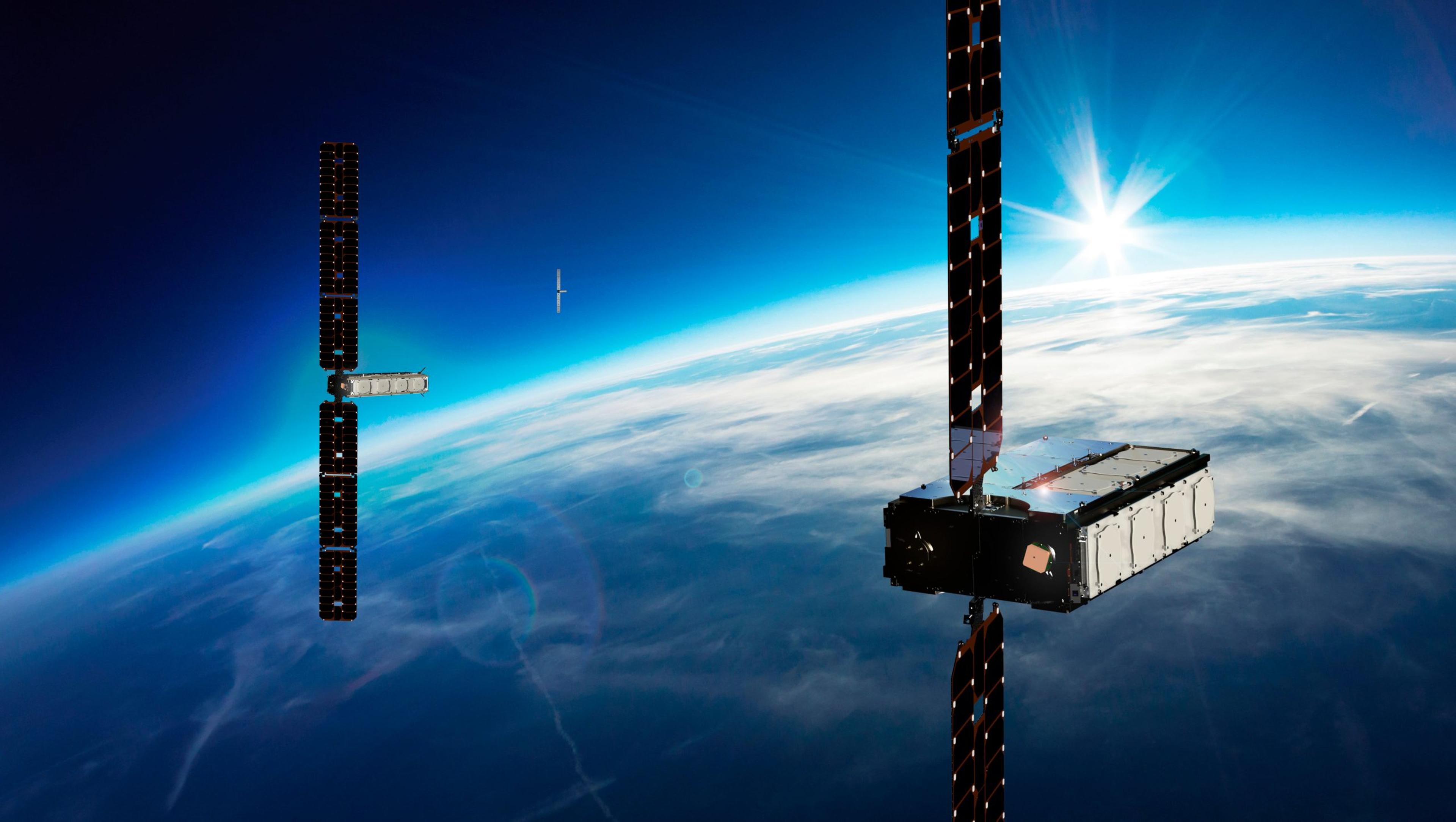

Satellite manufacturers see emerging market for ‘mini-constellations’

MOUNTAIN VIEW, Calif. — Manufacturers of small satellites that lack opportunities to build very large constellations say they are seeing growing interest from customers seeking smaller systems tailored to specific needs.

During a panel at the SmallSat Symposium here Feb. 10, executives from several small‑sat manufacturers described demand for “mini‑constellations” of dozens to a few hundred satellites for governments and companies that do not want to rely exclusively on megaconstellations such as Starlink.

“There’s definitely a market in large constellations, and a couple of companies are working hard to achieve that, but there’s a lot of value also in what we call mini‑constellations with five, 10 or 20 satellites,” said Jan Smolders, chief commercial officer at Space Inventor, a Danish small‑satellite manufacturer.

Those constellations could provide specialized services for customers that are not available from existing systems or that could be delivered more effectively through customized designs. “That’s something that we see and are working on,” he said.

Rusty Thomas, chief executive of Endurosat USA, the U.S. subsidiary of Bulgarian small‑satellite manufacturer EnduroSat, said he expects interest from companies and governments that may not want to rely on another company’s large constellation for critical communications or other services.

“One example would be a country seeking resilient communications through a system of 100 to 200 satellites. A lot of countries realize that they don’t want to rely on the megaconstellations for all of their communications,” he said.

Similarly, some large companies may find that custom constellations better meet their needs.

“Bigger companies will realize they don’t need to pay the megaconstellations for all their data services and could potentially put up 100‑, 200‑ or 300‑satellite constellations,” Thomas said.

“What drives business today is sovereign constellations and the realization for a lot of national players that they can no longer rely on global constellations,” said Slava Frayter, chief executive of GomSpace North America, a subsidiary of Danish small‑satellite company GomSpace.

Thomas said a system of 50 to 60 satellites would be sufficient to provide “constant custody,” or continuous coverage over a specific area, based on the experience of systems such as Iridium and Orbcomm.

Even smaller mini‑constellations are possible. Tina Ghataore, global chief strategy and revenue officer at Belgian manufacturer Aerospacelab, said a tailored system could provide rapid‑revisit imaging of a specific region.

“Thirty satellites will do it for you,” she said.

Mini‑constellations also offer manufacturers a chance to move beyond one‑off satellite projects, given that many of the very large constellations are built in‑house by operators, as SpaceX has done with Starlink and Amazon is doing with Amazon Leo.

The overall small‑sat industry is “not up to the standards and the scale that we need to maximize the opportunities that are out there in space currently,” said Peter Krauss, president and chief executive of Terran Orbital, a small‑satellite manufacturer owned by Lockheed Martin. He said the company’s top priority is developing economies of scale in small‑satellite production.

“Where we’re focused right now is that scalability, to change once and for all this notion of one‑off, bespoke, beautiful things. Instead, it’s about how we build things really and genuinely at scale: dozens of something, hundreds of something.”

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...