The Myth of ‘Always On’: Confronting Data Center SPOFs

•February 17, 2026

0

Companies Mentioned

Why It Matters

These vulnerabilities threaten service continuity for enterprises and cloud providers, potentially causing revenue loss and reputational damage. Strengthening design, redundancy, and staff competence is essential for market confidence.

Key Takeaways

- •Texas freeze exposed fuel resupply vulnerabilities in data centers.

- •OVH fire showed passive cooling can accelerate fire spread.

- •Tier IV redundancy costly; many operators settle for Tier III.

- •Human error remains top cause of data‑center outages.

- •Rigorous training and staffing reduce procedural failures dramatically.

Pulse Analysis

The 2021 Texas winter and the OVH Strasbourg fire illustrate how seemingly peripheral factors—fuel logistics and airflow design—can become catastrophic single points of failure (SPOFs). In Texas, sub‑freezing temperatures halted road access, stretching the typical 48‑hour on‑site fuel reserve beyond its limits and forcing operators to confront the fragility of external supply chains. Meanwhile, OVH’s environmentally friendly passive cooling, intended to reduce energy consumption, inadvertently supplied oxygen to a UPS‑origin fire, showing that sustainability measures must be evaluated for unintended safety impacts.

Redundancy standards such as the Uptime Institute’s Tier system provide a framework for fault tolerance, but the financial reality often forces data‑center owners to adopt Tier III designs rather than the fully fault‑tolerant Tier IV. Tier IV promises dual power and cooling feeds, yet the added capital expense can be prohibitive, leading many facilities to accept calculated risks. Moreover, even certified Tier IV sites can falter if control logic, protection coordination, or operational procedures diverge from design assumptions, as seen when backup generators unintentionally re‑energized a fire‑affected site.

Beyond hardware, human factors dominate outage statistics. Mis‑pressed emergency switches, skipped inspections, and inadequate training routinely erode the resilience built into physical infrastructure. Industry leaders argue that systematic staff development, rigorous procedural documentation, and proactive staffing models are as vital as any redundant chiller or generator. By treating training as a strategic investment rather than a cost‑center, operators can mitigate the unpredictable nature of human error, turning near‑misses into learning opportunities and preserving the reliability that modern enterprises demand.

The Myth of ‘Always On’: Confronting Data Center SPOFs

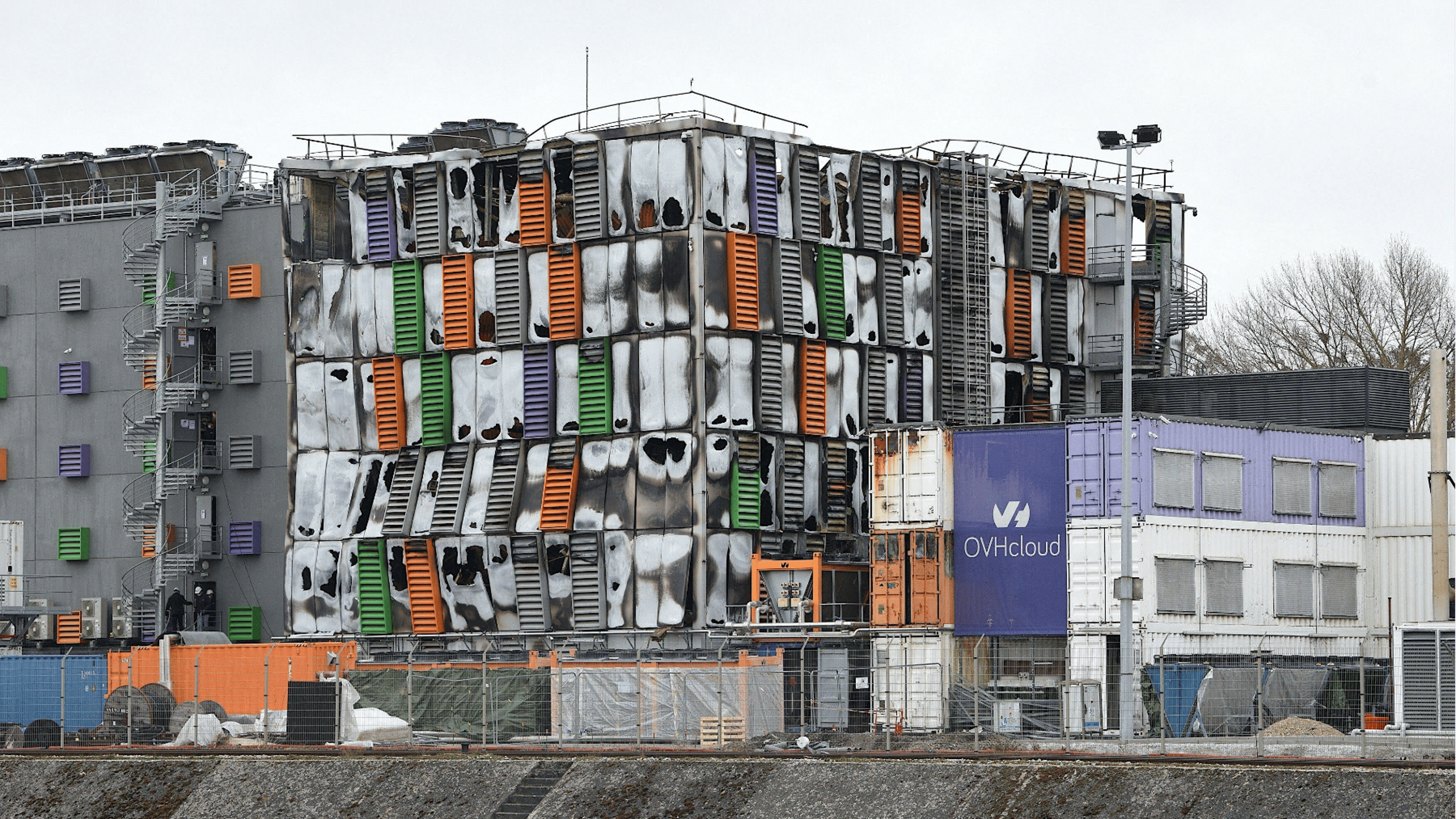

In March 2021, the OVH data center building in Strasbourg, France, suffered a fire caused by UPS‑related equipment.

Texas winters can swing from mild days to freezing nights. In February 2021, that volatility turned into days of sub‑freezing weather and snowfall across Northern Texas, exposing fragile assumptions about grid stability, on‑time fuel resupply, site access, and cross‑vendor collaboration. Most data centers stayed online, but several were pushed to the brink as blackouts spread and refueling and access plans unraveled.

Data centers are engineered to withstand the kinds of conditions Texas saw in 2021, but the weather event revealed off‑site dependencies that designs didn’t fully account for. A typical data center carries roughly 48 hours of on‑site fuel and backup generation; during the freeze, however, refueling was delayed by icy roads and interstate closures. Netrality’s chief operating officer, Josh Maes, later admitted the sustained, region‑wide disruption to fuel logistics had been undermodeled.

Related: Outsmarting Data Center Outage Risks in 2026

Just a month later, a different failure mode surfaced in Strasbourg, France, when a fire traced to UPS equipment destroyed OVH’s SBG2 data center. The facility’s environmentally friendly passive cooling earned sustainability brownie points, but the same airflow helped fan the flames once the fire broke out. As responders frantically worked to cut power to the facility, the backup generators unexpectedly kicked in after the main supply was cut – an example of control logic behaving as designed in one context but dangerously in another. Fire safety is as much about airflow management and shutdown coordination as it is about suppression hardware.

Taken together, these incidents highlight the ‘unknown unknowns’ that can lurk in any data center – the single points of failure (SPOF) that may be built in from the outset, accumulate through upgrades over the facility’s life, or surface through plain human error.

Engineering Out Single Points of Failure

Of course, designers and operators anticipate potential SPOFs long before the first mouse click is made in AutoCAD.

“The key ones are power redundancy to the site,” said Matt Wilkins, Global Director of Design and Engineering at Colt Data Center Services. “We've got dual‑redundant power supplies from different systems to ensure that power is uninterrupted. We've also, obviously, got backup generation on our sites to ensure that these key components can be maintained without causing disruption.”

Wilkins continued: “We have redundancy within the cooling system itself – multiple chillers – but we also have multiple redundant power supplies to them. We're also 100 % carrier neutral so that our customers can use the carrier of their choice, which maximizes cost efficiencies for them [and helps ensure] redundancy and uptime.”

Related: Comparing Data Center Backup Power Systems

But many data‑center designs fall short of total redundancy for pragmatic cost reasons, said Ed Ansett, Global Director, Data Center Technology and Innovation at Ramboll.

“Data centers are generally designed with a high degree of fault tolerance. That basically means that in the event that something fails, something else – a redundant component – will take over.” – Ed Ansett, Ramboll

During data‑center design, teams run SPOF assessments to uncover weak links, then decide to either eliminate them or accept them. That decision is primarily based on likelihood, impact, and cost.

What Tiers Do – and Don't – Guarantee

This is where standards frameworks such as the Uptime Institute’s Tier Standards come in – giving prospective customers a clear idea of the assessed risks of a data‑center’s design. Alongside Uptime’s certification system, there are similar alternatives: the Telecommunications Industry Association’s TIA‑942 and the European EN 50600 standards.

Related: Voltage Ride‑Through: A Key Ingredient in Data Center Resilience

Broadly speaking, these frameworks align with the four‑tier paradigm established by the Uptime Institute, with Tier IV promising complete fault tolerance.

“Tier IV says that you have a completely duplicate feed,” Ansett noted. “It’s predicated on the idea that the IT load, which is what everybody is concerned with, is dual‑fed from both a power and cooling perspective. That means that if one entire system fails, there is an alternative system that will be able to pick it up seamlessly.

“But that’s quite expensive, so there’s really a big compromise in Tier III. Because of the way that the various standards work, if you don’t meet the requirements, you automatically default to the next tier down,” he said.

More importantly, certifications do not remove risks. If control settings, protection coordination, or operating procedures diverge from design assumptions, even Tier IV data centers can fail.

Minor Faults, Big Consequences

Publicly documented outages show that it’s rarely a single failure that brings a data center down; more often, two or more issues act in concert. In 2014, when the Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX) experienced hours of downtime, external investigators, including Ansett’s data‑center consulting company i3 Solutions, detailed a chain of events. A malfunction in a component of one of the two diesel rotary uninterruptible power supplies (DRUPS) created a frequency mismatch between power sources. Downstream static transfer switches (STS) were not configured to handle the resulting out‑of‑phase transfer. The ensuing surge in current tripped breakers and cascaded across the primary data center. In other words, a sequence of failures exposed a design vulnerability that testing had not caught.

DRUPS‑related issues have been implicated in several other data‑center outages, including ones affecting AWS’s Sydney Region in June 2016 and Sovereign House in London in November 2015. Contributing factors can include synchronization faults, voltage sags, contaminated or degraded fuel, maintenance problems, and, of course, human error.

People Problems

Indeed, it’s not just technical and design shortcomings at issue. The biggest risks often stem from the people operating the data center.

“The spectrum of human error occurring in data centers is quite broad,” said Madeleine Kudritzki, Vice President of Professional Services Program Management at Uptime Institute.

According to Kudritzki, Uptime has seen a wide range of human errors at client sites – from untrained security officers hitting the emergency power‑off button instead of a door‑lock release, to tools being dropped into critical equipment, to skipped inspections that missed generator leaks, and even intentional shortcuts where key procedural steps are ignored under the guise of “seniority” and “expertise.”

“There are mistakes that happen, and there are intentional lapses in judgment. This is why mitigation of human factor risk is so complicated – it’s multi‑faceted and unpredictable.” – Madeleine Kudritzki, Uptime Institute

Training, Staffing, and Procedural Rigor

As an industry, she added, the data‑center sector needs more formalized staff development that goes beyond skill sets to emphasize applied knowledge, confidence, and effective, documented procedures when incidents occur. Those incidents should be leveraged as learning opportunities, not hushed up to avoid embarrassment.

A lack of rigorous enforcement of procedures is a recurring theme in Uptime’s Abnormal Incident Report (AIR) database. “There are recurring themes around organizational decisions that contributed to the failure of equipment, such as lack of preventative maintenance, incorrect procedures, or team members not properly following procedures,” Kudritzki explained.

She emphasized that this isn’t a capital cost but a matter of managerial will and commitment to devoting staff time to training, preventative maintenance programs, and active compliance monitoring. Unfortunately, these are often treated as low‑hanging fruit for corporate cost cuts.

While eliminating human error is impossible, one consistent issue Uptime has observed across hundreds of assessments is inadequate training – treated as a check‑the‑box exercise instead of the foundation of organizational resilience. “Data center operators are assigned recorded training with little to no record keeping, nor an assessment to check on the understanding of the material,” Kudritzki noted.

Operators also all too frequently underestimate required staffing levels, a problem exacerbated by industry‑wide skills shortages.

“Understanding the challenges with labor shortages, operators need to base their staffing levels around the number and timing of operational activities,” Kudritzki said. “Starting with the inventory of equipment, operators need to map out all the critical activities for each type of infrastructure, and add rounds and ongoing activities.

“Factoring in holiday and vacation, the result should be a determined number of hours that show exactly how many full‑time employees are needed to properly operate a facility.”

Furthermore, operational management needs a better appreciation of the individual factors that can trigger human error and how to address them proactively, she said. Too often, people are scrutinized only during a post‑incident root‑cause analysis, because organizations rarely identify and correct misunderstandings or overconfidence at the individual level in advance.

The Bottom Line

No matter how thoroughly operators work to design out potential failures, test every facet of infrastructure, and hammer home operational risks through training, something will eventually go wrong. After all, even Google is prone to occasional outages, such as an August 2022 electrical incident at its Council Bluffs, Iowa, facility that injured contractors and caused service disruptions.

The difference between a near‑miss and an outage is rarely another generator or chiller; it’s a cohesive approach that combines thoughtful design with verified controls, disciplined procedures, and a culture that learns from incidents rather than burying them. If Google isn’t immune to such failures, no one is. However, with the proper practices, failure can be made rarer, smaller, and less consequential.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...