China Debt Ratio Exceeds 300 Percent of GDP Mark

•February 9, 2026

0

Why It Matters

Understanding China’s soaring debt levels is crucial for investors and policymakers because it signals a shift from debt‑driven growth to debt‑sustained stability, raising risks of fiscal strain and financial instability. The episode’s timing is relevant as global markets watch how China’s government will manage this debt load amid weak nominal growth and a lingering real‑estate downturn.

China debt ratio exceeds 300 percent of GDP mark

For the first time, China’s official total debt exceeds 300 percent of gross domestic product. The National Institution for Finance and Development reports a macro debt ratio of 302.3 percent for 2025. The debt of households, non-financial companies, and central and local governments is measured in relation to nominal GDP. Financial institutions are excluded from this definition.

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!zA4x!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fceb1134b-5c52-450e-bb8c-85ad30868372_1536x1024.png)

Generated by AI (DALE-E3)

Government Drives Up China’s Debt

The publication marks a new high for the macro leverage ratio. It comes in a year of unusually weak nominal growth. While real gross domestic product grew by around five percent, nominal GDP grew by only around four percent.

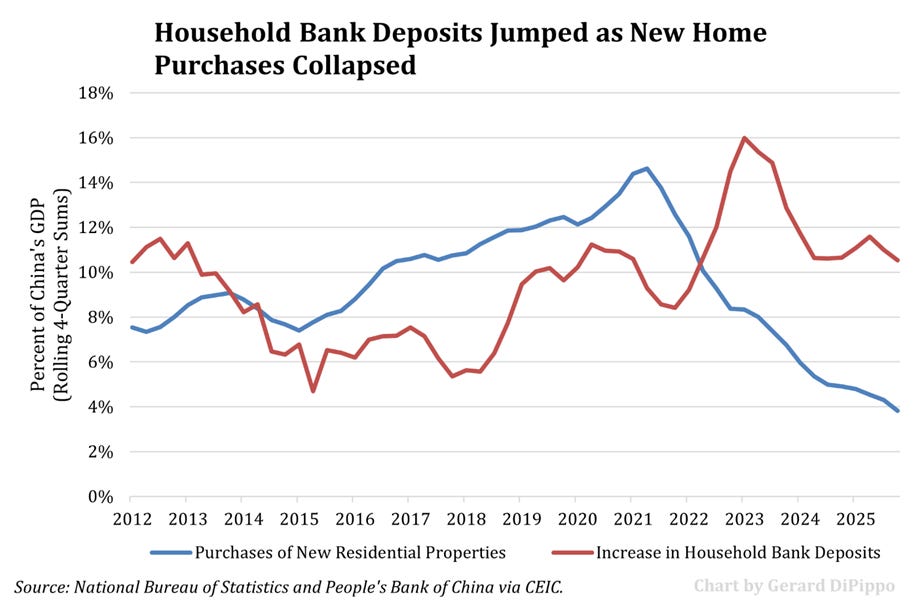

The sectoral breakdown confirms this picture. Households actually reduced their debt. The growth in their liabilities fell to 0.5 percent in 2025, a record low. The real estate crisis is having a double effect here. New purchases are not being made, while existing mortgages are being repaid early. High real interest rates are exacerbating this effect. Companies also held back. Credit growth was around four percent and was almost entirely attributable to state-owned enterprises. Borrowing by private companies stagnated almost completely.

The government is the main driver of debt. The government debt ratio rose by 7.6 percentage points in 2025. Without this increase, the overall ratio would have fallen. Fiscal programs, infrastructure investments, and the stabilization of local budgets kept the economy going, while households and private companies reduced their borrowing. The government thus took on the role of demand driver, replacing missing consumption and investment with credit-financed spending. This shift in the debt burden toward government and government-related entities is visible in the MLR, but there it tends to mark the lower end of the actual burden.

To put this into perspective, it is therefore crucial to look at total social financing (TSF). TSF is the measure of the total financing volume of the real economy. It includes bank loans, bonds, off-balance sheet financing, and government-related credit channels. If we compare the outstanding TSF stock with nominal gross domestic product, China’s debt ratio has been higher than the NIFD measurement for some time now. For 2025, this amounts to around 320 percent of GDP.

The difference between the two figures refers to debts that actually exist and are financed, but only appear partially or with a delay in the official MLR definition. These include, in particular, obligations of local government finance vehicles (LGFVs) and debt restructuring via state-controlled channels. They appear in the TSF because they burden the financing cycle. In the MLR, they are recorded more conservatively.

Real Estate Crisis Drains Demand from the Economy

The reason why this debt is hardly generating any growth can be explained by the household sector. The low share of household consumption in GDP is not a new phenomenon and is not solely the result of high savings rates. For many years, a large proportion of savings flowed into residential real estate and thus into real investment. Households thus contributed massively to domestic demand not only through consumption but also through capital formation. Construction, industry, and local finances benefited from this.

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8Wdz!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc20c812e-592b-42aa-a3fc-8c303a816366_922x605.png)

This model has been broken since the real estate crash. Households continue to save, but hardly invest in real terms. Funds flow into bank deposits and increasingly into financial investments. This is rational from the households’ point of view, but it does not replace demand. Although services are gaining in importance, they only compensate to a limited extent for the loss of real estate-driven demand. This is precisely where the gap arises that the state is now filling with debt.

This also explains the apparent contradiction between weak demand for credit in the private sector and rising overall debt. Households and private companies are pulling back, and the government is stepping in. At the same time, nominal growth remains weak. In this situation, the debt ratio inevitably rises, regardless of whether you look at the MLR or the TSF.

The new NIFD figure thus confirms what the TSF has been signaling for some time. Debt is not growing because of excessive demand, but because of a structural hole in the domestic economy. Whether the figure is 302 or around 320 percent makes little difference to the findings. The crucial point is that debt has lost its former role as a driver of growth and is increasingly becoming a prop for a system that would run more slowly without it.

0

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Loading comments...